Publications

- Category: Digital Law

Law 14,478/2022, which creates a civil framework for the crypto economy in Brazil, was published on December 22, 2022.

The new Law has become part of the Brazilian legal system, and will enter into force in 180 days after its publication.

Among the approved propositions, the following stand out:

- The creation of the legal categories of "virtual assets" and "virtual asset service providers", in line with FATF´s recommendations.

- The determination that virtual asset service providers must obtain a license to operate before an entity to be appointed by the Federal Public Administration.

- The determination that the activities developed by virtual asset service providers are guided by principles of free initiative and free competition, information security and protection of personal data, protection of popular savings, protection of consumers and users, protection against money laundering, among others.

- The application of the Consumer Defense Code to operations carried out in the virtual asset market, whenever appropriate.

- The submission of virtual asset service providers to Law 13,506/2017, which provides for the administrative sanctioning process of the Central Bank of Brazil and the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission, within the limits of responsibility of each entity.

- The equalization of virtual asset service providers to financial institutions for criminal purposes and the consequent subjection of these companies to the penalties of Law 7,492/1986, which defines crimes against the National Financial System.

- The creation of the crime called "fraud in the provision of services of virtual assets, securities or financial assets".

- The inclusion of the activities of virtual asset service providers within the scope of the anti-money laundering law (Law 9,613/98), and the increase in penalty from 1/3 (one third) to 2/3 (two thirds) if the crime (money laundering) is committed repeatedly, through a criminal organization or through the use of virtual assets.

- The discipline of the National Registry of Politically Exposed Persons (CNPEP) by act of the Federal Public Administration.

- The creation of conditions and deadlines, not less than 6 months, by the entity to be appointed by the Federal Public Administration for adapting virtual asset service providers that are already in operation to the requirements of the future Law.

Machado Meyer´s team remains attentive to the regulatory movement in the crypto asset sector in Brazil and abroad.

- Category: Environmental

On October 27, 2022, the Environmental Agency of the State of São Paulo (Cetesb) published the Cetesb Board Decision 106/2022/P, which establishes applicable procedures for issuance of technical opinions relating to:

- management of contaminated areas;

- reuse of contaminated areas;

- deactivation and demobilization of potentially generating activities of priority contaminated areas for licensing and decommissioning; and

- granting of groundwater collection wells around contaminated areas.

The first aspect extracted from the new board decision is the emphasis on the procedures relating to deadlines.

According to Article 3, deadlines count on calendar day basis (including weekends, holidays and non-business days), excluding the starting day and including the due date. Cetesb also established that the agency will consider the date that the party became aware of the first or second instance decision rendered by the agency and of other notifications issued in the proceeding as the day in which the confirmation of the reading of the “Communicate” (Comunique-se) notification occurs or automatically after the tenth day from the issuance of the electronic message to the address registered on Cetesb's website – whichever comes first.

Articles 5 to 7 of the Cetesb Board Decision 106/2022/P regulate the competence to issue technical opinions and decide on occasional challenges to the actions, in first and second instances, as follows:

- Technical opinion on the management procedure of contaminated areas: is issued by the Industrial Contaminated Areas Assessment Management Sector (ICRI) or the Gas Station Contaminated Areas Assessment Sector (ICRP). In the event of filing of administrative defense against any unfavorable opinion issued by the agency, the decision shall be rendered by the Administration of the Contaminated Areas Management Department (IC). In case of appeal against the decision of first instance, the trial will be held by the Board of Environmental Impact Assessment;

- Technical opinion on the procedure for reusing contaminated areas: is issued by the Management of the Contaminated and Rehabilitated Areas Assessment Division (IRA). In the event of submission of an administrative defense against any unfavorable opinion, the decision shall be rendered by the Management of the Department of Management and Revitalization of Contaminated Areas (IR). The Board of Environmental Impact Assessment is responsible for handling the trial of any appeal;

- Technical opinion on the procedure for obtaining and renewing well concessions around contaminated areas: is issued by the Management of the Grant Assessment Sector (IRAO). In the event of submission of an administrative defense against any unfavorable opinion, the first instance decision shall be rendered by IRA. If an appeal is later filed, the second instance decision on the matter will be issued by the IR; and

- Technical opinion on evaluation of Decommissioning and Demobilization Plan: is issued by the Management of the Environmental Agency. In the event of filing of administrative defense against unfavorable opinion, the first instance decision shall be rendered by the Management of the Department of Environmental Management, and the Board of Environmental Control and Inspection is responsible for the judgment of any appeal.

The new decision of the board established a deadline of 15 days, counted from the date of its acknowledgment, for the submission of an administrative defense against a technical opinion. If a decision is rendered in the sense of maintaining the previous opinion, the interested party will be notified to, also within 15 days, file an administrative appeal for judgment in second (and last) instance.

As for the means of procedural communication, the interested party – that is, a natural or legal person that requests the issuance of a technical opinion on contaminated areas before Cetesb – will be notified of the result of the technical analysis by a message on the electronic platform used by the agency. In this same platform, the interested party may even monitor the procedural progress and update registration data.

The Cetesb Board Decision 106/2022/P also determines that the administrative procedures for the issuance of technical opinions on contaminated areas begin with the filing of the request protocol (SD) on the electronic platform used by Cetesb.

In its final provisions, the document determines that proceedings not handled by interested party for 120 days will be filed by Cetesb. However, during this period, upon reasoned justification, an extension of the deadline may be requested, which must be assessed by the competent authority for issuing the technical opinion.

The new decision of the board, therefore, updated the procedure to be observed for requesting and issuing technical opinions by Cetesb’s various entities and provided information on the counting of deadlines, competence for the drafting of the aforementioned technical opinions, types of communication of procedural acts, appeal bodies and competent authorities for judgment.

- Category: Intellectual property

The first version of Disney's most classic character, Mickey Mouse, brought to public on October 1, 1928 in the short Steamboat Willie, is expected to enter into the public domain in the United States in 2024. What does this event mean in practice? To answer the question, we need to look at some points, starting with the history of the protection of intellectual property rights in the United States and this character.

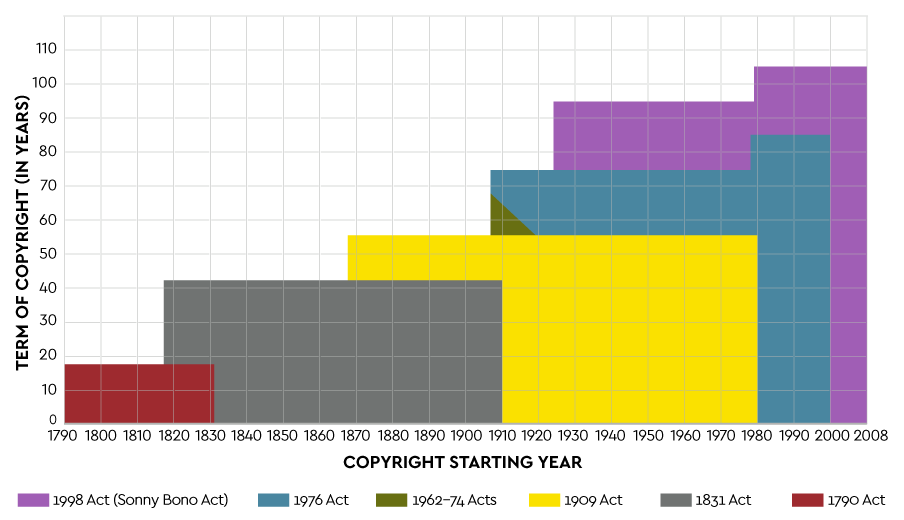

In 1790, the year of the promulgation of the first U.S. copyright legislation, the term of protection was 14 years from the elaboration of the work.[1] Several subsequent legislative changes extended the protection period, especially from the 1960s onwards, as shown in the following graph:

The last change in U.S. copyright legislation occurred in 1998, with the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act, popularly known as Mickey Mouse Protection Act, given Disney's strong support for the project.

The law extended the period of protection of a work created on or after January 1, 1978. As a rule, the end of protection passed to 70 years after the death of the author. In the case of anonymous, pseudonyms or custom-made works, the protection period was extended to 95 years from the year of first publication or 120 years from the year of creation, whichever expires first.

The first version of the character Mickey Mouse was created co-authored by Walt Disney, who died in 1966, and Ub Iwerks, who died in 1971. The publication took place in 1928 and had its registration renewed. Considering that, the copyright protection ends after 95 years, i.e. in 2023. Thus, from January 1, 2024, in principle, anyone will be able to use this version of the character without violating Disney's copyright.

However, as pointed out by specialists in the legislation in question, the public's use of the first version of the character is not unrestricted. Disney maintains the protection of such version of the character, as well as newer versions, as a trademark. This protection can be presented to prevent or limit certain uses of the character, such such as selling merchandise in which the character is depicted. In this case, it could be suggested that the merchandise is a product produced or licensed by Disney.

Other Disney characters have already entered into the public domain in the United States earlier this year, such as Winnie-the-Pooh (Puff Bear), Piglet and Bambi. The loss of Disney's exclusivity over these characters has already resulted in a film production made by a third party, not yet published.

Considering that it is possible to compare the main character with Puff Bear, it is observed in the production trailer that the context in which it is inserted, as well as its countenance at times, distances the work from traditional Disney cinematographic productions, as it is associated with the horror genre. This was one of the strategies for using the character in the public domain without violating Disney's trademark.

But how does Brazilian legislation work? Are these and other characters in the public domain (in the United States or other countries) also in the public domain here?

In Brazil, copyright is regulated by the Federal Law 9,610/98 (Copyright Law). Article 41 of that law states that, in general, the author's patrimonial rights last for 70 years, from January 1st of the year following the author's death. After this period, the work falls into the public domain and is returned to the community so that everyone can use it freely, free of charge, respecting only its integrity and the author's credit.

For Disney characters in the public domain (as well as any works previously protected by copyright in the same situation) to be used free of charge in Brazil, some points must be considered.

Firstly, the minimum period of protection for a foreign work to be considered in the public domain is 50 years from January 1 of the year following the death of the author of the work, as established in Article 7 of the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, of which Brazil is a signatory, and dated September 9, 1886. This term applies even if the country of origin of the author or work establishes a shorter term of protection.

Secondly, Articles 7 and 8 of the Berne Convention provide that the duration of the protection shall be governed by the law of the country in which the protection is claimed and may not exceed the duration established in the country of origin of the work, unless there is an internal legal provision in contrary.

According to the legal text of Article 2 of the Copyright Law, Brazil undertakes to grant foreign works the same legal protection assigned to Brazilian works, provided there is reciprocity, that is, provided that Brazilian works are protected in foreign countries under their own laws.

This means that, in Brazil, Brazilian and foreign works are protected for the same period, that is, 70 years from January 1st following the year of the author's death.[1]

In the case of the first version of the character Mickey Mouse, therefore, Brazil grants copyright holders exclusivity in the economic exploitation of the works for 70 years from January 1 of the year following the author's death.

As the United States confers the same right for 95 years, counted from the date of the first publication of the work, this means that the first version of the Mickey Mouse character will fall into the public domain in the United States before falling in Brazil. Here, as it is a work carried out in co-authorship, it will obtain this status only in 2042 – since, according to Article 42 of the Copyright Act, the term is counted from the death of the last of the surviving co-authors (in this case, Ub Iwerks, who died in 1971).

As seen, the entry of copyright in the public domain must be analyzed in accordance with the legislation of each country. Therefore, it is up to those who intend to use illustrations, literary works, and other intellectual works, freely and free of charge, to verify whether these creations are in the public domain, according to the legislation of the country in which they are intended to be used.

[1] BRANCO, Sergio. The Public Domain in Brazilian Copyright Law, 2011, p. 153.

[1] 1790 Copyright Act

- Category: Litigation

The granting of precautionary measures, in particular those involving the freeze of assets, must comply with the general legal requirements of risk demonstration to the useful outcome of the process and/or danger of irreparable damage. The jurisdiction of the Court of Auditors of the Union (TCU) in relation to that question is based on Article 44( 2).[1] of the Organic Law of the TCU (Law 8,443/92), on Article 274[2] of the Rules of Procedure of the TCU and on the subsidiary application of other legal provisions, such as the Law of Administrative Improbity[3] (Law 8,429/92). However, this type of order is the subject of criticism and legal disputes.

On one hand, it is understood that the powers of the TCU are restricted to Articles 71 and 72 of the Federal Constitution and, consequently, would not include precautionary and enforceable measures, which would be restricted to the Judiciary. In fact, both the Organic Law of the TCU and its bylaws would extrapolate the powers delegated to the court by the Federal Constitution.

On the other hand, as decided in the leading case Security Warrant 24,510 – MS 24,510, the TCU has this competence based on the theory of implicit powers.[4] According to the decision, TCU’s orders would only be enforceable against third parties if the court has sufficient powers to execute them, and not always depend on the judiciary.

On October 13, 2022, the Supreme Court ruled the MS 35,506 and consolidated its understanding[5] that the courts of accounts have the power to adopt grant precautionary measures, "as long as they do not go outside their constitutional duties". In this case, the TCU ordered the freeze, for one year, of R$ 653 million of the Industrial Plants Project Ltda.’s assets (PPI), and confirmed its previous decision to pierce the PPI’s corporate veil – all in the administrative scope.

According to Minister Lewandowski, whose vote was the winner, "the public origin of the resources involved justifies that the injunction reaches individuals and not only public agencies or agents.". Regarding the disregard of the corporate entity of PPI, the Minister defended its possibility as a way to suppress abuses and frauds by the use and manipulation of the corporate entity.

Aware of the questions about the limits of its powers, the TCU has for years granted constriction orders of investigated assets. In many cases, the decisions are based on the generic risk to the useful outcome of the process considering the possibility of assets dissipation. Those decisions did not include what was the true evidence of eventual assets dissipation, especially in cases involving accusations of administrative misconduct and embezzlement of money.

Nevertheless, the consequences of the freeze orders go beyond the guarantee of payment of any conviction in the proceeding. An order preventing the disposal of assets by the respondent directly affects the companies’ capital and individuals’ finances, resulting on undesirable and critical financial situations.

These measures contradict the principle of the preservation of the company, surpassing the object of demand and affecting, in a macroeconomic analysis, the guarantee of jobs, income generation, maintenance of balanced and stable finances. The decision given in a process, administrative or judicial, may result in problems to the society as one.

Considering the above-mentioned consequences, the freeze orders granted by the TCU must be reasonably founded, demonstrating in the specific case the alleged irreparable damage or the risk to the useful outcome of the proceeding. In other words, the freezing injunction must be based not only on legal aspects, but on evidences of the real risk of not granting it.

[1] Art. 44. At the beginning or in the course of any investigation, the Court, in a letter or at the request of the Public Prosecutor's Office, will determine, in a precautionary, the temporary removal of the person responsible, if there are sufficient indications that, continuing in the performance of his duties, may delay or hinder the performance of audit or inspection, cause further damage to the Treasury or make his compensation unfeasible. [...] § 2 - In the same circumstances as the caput of this article and the preceding paragraph, the Court may, without prejudice to the measures provided for in the arts. 60 and 61 of this Law, decree, for a period of not more than one year, the unavailability of assets of the responsible person, as many as considered enough to guarantee the compensation of the damage in investigation.

[2] Art. 274. In the same circumstances as the previous article, the Plenary may, without prejudice to the measures provided for in the arts. 270 and 275, decree, for a period of not more than one year, the unavailability of assets of the responsible person, as many as considered enough to guarantee the reimbursement of the damages in investigation, pursuant to § 2 of Article 44 of Law 8.443, of 1992.

[3] Art. 16. [...] § 4 - The unavailability of assets may be decreed without the prior hearing of the defendant, whenever the prior adversarial may prove to frustrate the effectiveness of the measure or there are other circumstances that recommend the injunction, and the urgency cannot be presumed.

[4] As Luciano Ferraz explains, "The theory of implicit powers was constructed by the United States Supreme Court in the famous case McCulloch v. Maryland (1819), and is based on the idea that the granting of express jurisdiction to a particular State body matters in the implicit acceptance, also to it, of the means proper to the full achievement of the purposes prescribed by the constituent. It is true that this theory was granted in relation to the legislative powers (implicit) of the Union before the states, based on the federal constitutional regime of the USA, but the fact is that it has already been widely used by the Supreme Court to justify hidden powers of organs such as the Public Prosecutor's Office, the National Council of Justice and the Court of Auditors". (available on Legal Advisor website).

[5] In the same direction: Security Suspension 5.455-RN and Security Warrant 34.446-DF.

- Category: Litigation

The discussion on the constitutionality of state laws that provide for the mandatory extension of promotional campaigns to all customers – new or pre-existing ones – of services of a continuous nature had another chapter in the judgment of Direct Actions of Unconstitutionality 6,191, 6,333 and 5,399 (ADI 6,191, ADI 6,333 and ADI 5,399). However, it was not a final chapter, because the Supreme Court's decision was restricted to promotions related to telecommunications and education service providers.

ADI 6,191 and ADI 6,333 were proposed by the National Confederation of Educational Establishments (Confenen), while ADI 5,399 was filed by the National Association of Cell Phone Operators (Acel). The lawsuits questioned Law 15.854/15 SP and Law 16.559/19 PE, according to which providers of continuous services (such as telecommunications, education, water, electricity, health plans, cable TV, internet providers, among others) are obliged to offer their old customers the same conditions offered to fresh consumers. In case of non-compliance, fines could be imposed.

At the trial, the Supreme Court ruled, by majority of votes, that the mentioned state laws were unconstitutional. For this, the Court based its decision on two main arguments, one of formal order and another of material order.

From a formal point of view, the Supreme Court pointed out that the contracts established between consumers and telephone operators or educational institutions are civil matters and, therefore, are subject to legislation that can only be created by the Federal Union, not by States. In addition, it was recalled that the Court had previously decided that only the Federal Union could legislate on education and telecommunications.

Regarding the material argument, the court pointed out that the state laws violate the constitutional principles of free enterprise and proportionality. The granting of discounts indiscriminately to old clients would hamper suppliers to seek new customers, which would breach the free enterprise principle. Furthermore, requiring service providers of an ongoing nature to amend the contracts already established would cause disproportionate damage.

Considering the arguments used by the Supreme Court, although the object of the actions are specific laws of São Paulo and Pernambuco, any similar state law would also, in principle, be unconstitutional. States with similar laws should, then, submit to the decision.

It is important to highlight that the Decision of the Supreme Court covered only promotions related to providers of education and telecommunications services, because the thesis created was: “the state law that imposes on private providers of teaching and cellular services the obligation to extend the benefit of new promotions to pre-existing customers is unconstitutional". Thus, by exclusion, other services of a continuous nature (such as health plans, internet providers and pay TV) would still be subject to similar state laws.

The analysis of the judgment of these ADIs leads us to believe that grounds used by the Supreme Court could also be applied to other services of a continuous nature. It is now worth following how other entities representing service providers of this nature will act, considering that there are several state and federal bills proposing that service providers are obliged to extend to their pre-existing customers the same conditions offered for new ones.

- Category: Tax

Legal entities depend on a range of auxiliary activities to make their businesses viable, such as legal and information technology services, advertising, accounting, human resources, and others.

To rationalize management, simplify procedures, and optimize resources, it is not uncommon for companies in the same economic group to choose to share these facilities, sharing the necessary expenses, whether to maintain internal departments or to hire external providers. These are called cost sharing agreements.

Despite being an atypical contract, not provided for in the Brazilian civil law, this instrument implies, most of the times, advance of expenditures inherent to the funding of these sectors by one of the participating entities, usually identified as a “centralizer", linked to financial reimbursement by the other beneficiaries, proportionally to the portion attributed to each entity.

Because it represents a mechanism of mutual contribution to finance advantages of common use, the duty assumed by the centralizing entity should not be confused with the provision of services covered by these structures, jointly enjoyed by the contracting companies.

This role is most often fulfilled by the agents actually hired and paid for the performance of the shared services, when the cost sharing model adopted involves the participation of third parties to deliver these services.

It is also unreasonable to affirm that the contributions made by the beneficiary companies and received by the centralizer, as reimbursement for anticipated expenses, should be considered indistinctly as revenue of the latter.

We should not forget that it is a characteristic of cost sharing that one of the contracting parties incurs expenses in advance for the benefit of the others, under a commitment to future reimbursement. In this type of arrangement, the amounts received by the centralizer, therefore, translate into a simple restoration of what was spent on behalf of the other contractual parties, without any associated economic advantage.

This insight is fundamental and the Federal Revenue Service of Brazil (RFB) had already taken it into account when it issued the Resolution of Divergence 23 of the General Coordinator’s Office of Taxation (SD Cosit 23/13), in which it expressed the understanding that it is possible to exclude from the PIS and Cofins calculation basis the amounts received as reimbursement by the centralizing legal entity of shared activities, precisely because they do not represent revenue, but rather cost recovery, without adding anything to the legal entity's assets.

The issue was addressed in a judgment by the 3rd Panel of the Superior Chamber of the Administrative Tax Appeals Board (CSRF), whose decision was published on May 11, 2022. In the judgment, by majority vote, financial income received by the centralizing company was ascribed the nature of revenue from provision of services, in the course of the flow of payments established through cost sharing, admitting the levy of PIS and Cofins on the items (Appellate Decision 9303-012.980).[1]

In a dissenting opinion, the reporting judge, Tatiana Midori, reasoned that the contractual model under analysis could not be confused with a service contract. This is because, besides not being for consideration and imposing reciprocal obligations, the amounts reimbursed would not be added to the recipient's assets, nor would they be capable of creating wealth or profit, since they represent "mere settlement of accounts". The reporting judge also pointed out that the company assessed had strictly followed the criteria for apportionment, accounting, and instrumentation,[2] listed in SD Cosit 23/13.

This view, however, was overcome by the vote of board member Luiz Eduardo Santos, according to whom the taxpayer had provided services to other legal entities (whether merely administrative or linked to the main activity) and received amounts for this.

To justify the levying of the contributions, the board member argued that:

- the characterization of revenue is independent of the division between non-core activity and core activity, with such discussion being merely doctrinaire and not originating from the law;

- there is no legal provision in the Brazilian tax legislation governing the treatment of apportionment of common expenses; and

- the Brazilian legal system provides that only in consortium contracts and powers of attorney, a certain expense can be incurred and passed on to a third party without being considered its own expense.

The reasoning above does not seem to be the most consistent with the position already expressed by the Federal Revenue Service of Brazil and, in view of this, we propose some reflections.

It is noteworthy that the decision has expressly concluded finding SD 23/13 inapplicable, understanding that it would not be of mandatory observance by Carf. However, it must be remembered that, according to article 33, of IN/RFB 2.058/21, the solutions of divergences handed down by Cosit have binding effect within the Federal Revenue Service and protect taxpayers who apply them.[3] This condition, therefore, derives from a legal standard.[4]

To finding otherwise would favor a scenario of generalized legal insecurity. This factor, in itself, would be enough to lead to the opposite result. Furthermore, the understanding on the merits reached by the CSRF itself left out, in our judgment, some crucial points that should guide the examination of the matter.

The ruling shows that it attaches too much importance to arguments that should be determinant in designating the nature of the amounts received. Even if it were possible to link to the centralizing company's activity the elements of provision of a service, which is certainly controversial,[5] as well explained in the dissenting opinion, the decision did not demonstrate the actual receipt of revenue linked to this provision of services, the taxable event of the taxes in question.

As can be seen, the judge builds his theory based on loosening of the concepts of “core activity" and “non-core activity" to portray the obtaining of revenue. In his view, practical experience makes this differentiation unfeasible, since certain services can fall into one category or another, depending on the allocation given by the company that receives them.

To justify the statement, the example of legal services is brought in, which could be understood as core activities, when consumed directly for the achievement of core activities, such as the conclusion of a company's business. The same expenditure would be classified as a core activity when reverted to the performance of activities of the same nature, citing tax planning as an example.

Thus, he explains that the cost sharing contract may gather services that assume a double condition, since, at certain times, they will be considered a core activity (due to their acting in favor of activities of this nature) and, at other times, they will be a secondary activity (due to their being invested in activities considered ancillary). Under this pretext, it is alleged that it would not be possible to rule out the nature of provision of a service performed by the centralizing company.

However, the function of any core activity on behalf of a legal entity is to produce consequences on its business, regardless of the sector in which it is absorbed and the degree of proximity with the corporate purpose. To some extent, all the activities contracted by the entity act to generate positive effects on its core business.

The fact that an activity is closer to the acts that are part of the entity's corporate purpose is not an impeding or excluding criterion to characterize it as a core activity. In other words, it is incorrect to state that core activities will be only those invested in ancillary activities of the entity.

Any activity performed on an auxiliary basis that is not typical of the core business should be interpreted as a non-core activity. The word itself is self-explanatory: “core activity" encompasses every role that does not have a purpose in itself, but serves as an instrument to achieve the corporate objective, whatever the business line may be.

Taking the example given in the judgment, the common objective of all legal services is essentially the same, that is, to provide legal support for the entity that avails itself of them. It will be, in any case, a non-core activity, which aims to optimize the result of the core activity, regardless of the context in which it is performed.

Furthermore, the grounds against the taxpayer neither invalidate nor counteract the premise that the expenses advanced by the taxpayer were incurred for the exclusive benefit of third parties, which is to say, the other beneficiaries of the cost sharing. Given this picture, the question is: how is it possible to ascribe the nature of revenue per se to the reimbursements received?

The answer could not be more straightforward: these amounts are not revenue. The taxpayer does not experience an increase in net worth capable of constituting revenue from the provision of services.

The application of this precept also inspires repercussion on the possibility of appropriating a PIS and Cofins credit on all of the amounts paid by the centralizing company under these contracts, when it involves the hiring of legal entities. That has to be guaranteed.

But the guarantee that should be pursued, after all, is not to see funds that do not have this characteristic taxed as revenue, as recognized by the Public Administration itself in SD Cosit 23/13.

Among the ills that plague our tax system and affect the good development of the business environment and the economy in Brazil, legal insecurity and lack of predictability in tax matters stand out. If, on the one hand, structural reforms that are difficult to implement can bring about a permanent solution, on the other hand, more targeted actions, potentially resulting from a necessary change in culture, would make a big difference.

It would be of enormous value to have the many doubts that permeate the application of our tax legislation answered by the Federal Revenue Service, as happened in the case of cost sharing. But this achievement will be worthless if the taxpayer cannot be sure that the agency's understanding will be generally followed by the Public Administration.

[1] Administrative Proceeding 19515.003333/2004-51.

[2] SD 23/2013 establishes that the portion attributed to each entity is calculated based on reasonable and objective apportionment criteria, previously agreed upon, formalized by an instrument signed between the intervening parties; that they correspond to the actual expense of each company and to the global price paid for the goods and services; that the centralizing company of the operation appropriates as an expense only the portion attributable to it according to the apportionment criteria, in an identical manner to the decentralized companies that are beneficiaries of the goods and services, and accounts for the portions to be reimbursed as rights to recoverable credits; separate accounting of all acts directly related to the apportionment of administrative expenses.

[3] Article 33. The solutions of consultations issued by Cosit, as of the date of their publication:

I - have a binding effect within the RFB; and

II - support taxpayers who apply them, even if thety are not the respective inquirer, as long as they fit into the scenario covered by them, without prejudice to confirmation of their actual classification by the tax authority in an inspection proceeding.

[4] National Tax Code (CTN):

Article 100. The following are complementary rules to laws, international treaties and conventions, and decrees:

I - normative acts issued by administrative authorities;

(...) Sole paragraph. Compliance with the standards referred to in this article rules out the imposition of penalties, charging of default interest, and adjustment for inflation of the monetary value of the tax calculation basis.

[5] The adoption of this premise seems to be materially inconceivable, since it would place the taxpayer in the simultaneous condition of provider and recipient of a single and indivisible service, as though it could be reproduced and passed on, as an effect of the contractual arrangement adopted.