Publications

- Category: Labor and employment

Published on September 5, Law 14,442/22 substantially amended the rules on food allowances and remote work.

The new law clarifies that the amounts paid by the employer as food allowance, provided for in paragraph 2 of article 457 of the Brazilian Labor Law (“CLT”), must be used for the payment of meals in restaurants and similar establishments or for the purchase of foodstuffs in commercial establishments.

The concept of food allowance encompasses both food vouchers and meal vouchers.

Regarding the hiring by employers of a legal entity to provide the food allowance, the legislation now states that the employer cannot demand or receive:

- any kind of discount or imposition of discounts on the contracted value;

- onlending or payment terms that denature the prepaid nature of the amounts to be made available to the employees; and

- other amounts and benefits not directly related to promotion of the employee's health and food safety in the contracts executed with companies that issue food allowance payment instruments.

The prohibitions on the relationship between the employer and the companies that provide the food allowance established by the law do not apply to contracts for the provision of food allowances in effect until their termination or until the period of 14 months has elapsed from the date of publication of the law (November 5, 2023), whichever occurs first. It is forbidden to extend a contract for the provision of a food allowance that does not comply with these prohibitions.

The new legislation establishes a fine ranging from R$5,000 to R$50,000, applied in double in the event of recurrence or obstruction against inspection, inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the food allowance by the employers or companies that issue the instruments for payment of the food allowance.

The establishments that sell products not related to employee nutrition and the companies that accredited them are also subject to a fine. The criteria and parameters for calculating the fine will be subject to an act by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security.

From a tax standpoint, the new legislation amends the provisions of Law 6,321/76, which deals with deduction from taxable income for corporate income tax purposes, to establish that corporate entities may deduct from taxable income, for corporate income tax purposes, twice the expenses proven to have been incurred during the base period in worker food programs previously approved by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, in the manner and limits set forth by the decree that regulates the matter.

The new law also establishes that expenses allocated to worker food programs (so called “PAT”) must cover exclusively payment of meals in restaurants and similar establishments and acquisition of foodstuffs in commercial establishments.

Law 14,442/22 reproduces in Law 6,321/76 the prohibitions on the relationship between the employer and the companies that provide food allowances (such as prohibition on any kind of discount on the contracted value). The prohibitions will be in effect as defined in the regulations for the worker food programs.

The new legislation also provides that food payment services contracted to carry out food programs must observe the following additional rules:

- placement into operation by means of closed or open payment arrangements, and companies organized in the form of closed payment arrangements, must allow interoperability among themselves and with open arrangements, indistinctively, to share the accredited network of commercial establishments, as of May 1, 2023, it is worth noting that operation of open arrangements is allowed as of now. 2023 is the date as of which the sharing of accredited networks will be mandatory, always respecting the commercial conditions established; and

- free portability of the service upon express request of the worker, in addition to other rules set forth in a decree from the Executive Branch, as of May 1, 2023.

In relation to the penalties applicable in the event of inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the worker food programs by the beneficiary legal entities or companies registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, the new legislation introduces a provision in Law 6,321/76 that establishes the same fine mentioned above, in the same terms.

Furthermore, it establishes as a penalty the cancellation of registration of the beneficiary legal entity or registration of companies linked to the worker food programs registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, as of the date of the first cancellable irregularity and, consequently, loss of the tax incentive of the beneficiary legal entity.

If the registration of the beneficiary legal entity or registration of the companies linked to the worker food programs registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security is cancelled, a new enrollment or registration with the same ministry can only be requested after the deadline to be defined in regulations.

It is important to explain that the penalties established by Law 14,442/22 as a result of inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the food allowance by employers or companies that issue instruments for payment of the food allowance are applicable to all companies, regardless of whether they are enrolled in food programs, with the exception, of course, of cancellation of the registration of the legal entity in food programs, applicable only if the company is enrolled in a food program.

Due to the changes introduced, companies must reevaluate their food allowance programs to adapt them to the new rules, both from the labor/employment perspective and from the tax and regulatory perspective, especially companies that adopt flexible benefits policies.

In addition to the changes regarding the food allowance, Law 14,442/22 also introduced changes regarding remote work. We addressed this topic in another article, available through this link.

Machado Meyer Advogados will continue to monitor the evolution of the matter and its potential developments. Keep up with our publications by subscribing to our newsletter.

- Category: Tax

Executive Order 1,137, published on February 21 of this year, introduced a zero rate for withholding income tax (IRRF) on income paid to foreign investors. The goal is to attract foreign credit and encourage the issuance of private debt securities.

After republished in an extra edition of the Official Gazette of the Federal Government on the same date, MP 1,137 also changed the legal regime applicable to foreign investment, regulated by CMN Resolution 4,373, in equity investment funds (FIP), among others.

The MP incorporates some provisions that were being discussed in Congress in the scope of Bill 4,188, the substitute of which had already been approved by the House of Representatives in June of this year and became known as the Legal Framework of Guarantees.

The measure takes effect January 1, 2023, and must be converted into law within 60 days, extendable for another 60 days.

Main changes

| Change | Requirements and conditions - who can benefit |

|

The previous rules regarding the composition of FIP's portfolio (minimum limit of 67% of shares of joint stock companies, convertible debentures, subscription warrants, and debt securities in a percentage greater than 5% of the net equity) have been revoked.[1] There is compatibility and alignment with the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil (CVM). The restriction on applying the zero tax rate to foreign investors who hold more than 40% of the FIP’s units was also revoked. Expansion of the benefit to: · foreign investors who are shareholders in FIP-IE and FIP-PD&I; and · sovereign wealth funds.[2] Important: expansion of the restriction on the application of the zero tax rate for investors domiciled in a tax-favored jurisdiction to beneficiaries of a privileged tax regime[3] (except sovereign wealth funds). |

· securities subject to public distribution, issued by private legal entities, excluding financial institutions;[4] · FIDC whose originator or grantor of the credit rights portfolio is not a financial institution and other institutions authorized to operate by the Central Bank of Brazil; · financial notes; and · investment funds that invest exclusively in: - securities mentioned above; - federal government securities; - assets producing exempt income referred to in the MP; and - repo operations backed by federal public securities or units of investment funds that invest in federal public securities. *The MP defines income as "any amounts that constitute remuneration of invested capital, including that produced by variable income securities, such as interest, premiums, commissions, bonuses, and discounts, and positive results from investments in investment funds.” |

· The securities must be registered in a registration system authorized by the Central Bank of Brazil or by the CVM. · FIDCs and CRIs can have as objective the acquisition of receivables from only one assignor or debtor. · The FIDC units must be admitted for trading in an organized securities market or registered in a registration system authorized by the Central Bank of Brazil or by the CVM. Exceptions: transactions entered into between related parties[5] and an investor domiciled in a tax-favored jurisdiction or beneficiary of a privileged tax regime do not qualify for the 0% tax rate (except in the case of a sovereign wealth fund). |

[1] Repeal also applicable to the general regime for investments in FIP (15% tax rate).

[2] Foreign investment vehicles whose assets are composed exclusively of funds derived from the sovereign savings of the respective country.

[3] As per IN 1,037/2010.

[4] The following are considered to be financial institutions: banks of any kind; credit cooperatives; savings banks; securities distribution companies; foreign exchange and securities brokerage companies; credit, financing, and investment companies; real estate credit companies; and leasing companies.

[5] As defined in subsections I to VI and VIII of the head paragraph of article 23 of Law No. 9,430/96.

- Category: Tax

In recent years, incentives for electric and electrified vehicles, such as hybrids and plug-ins, have become increasingly common. This is because these vehicles are seen as a way to tackle the climate crisis by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In the state of São Paulo, for example, the Pro Green Vehicle program, created in March of 2022, aims to encourage the development of industrial companies assembling less polluting motor vehicles through the immediate monetization of accumulated ICMS credits. For commercial companies of this type of vehicle, the São Paulo state government reduced the ICMS tax levied on the marketing and sale of trucks, buses, and electric and electrified vehicles from 18% to 14.5% as of January of this year.

The market for electric and electrified vehicles is tending to become even more consolidated, as pointed out in the report by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which estimates an almost 500% growth in the production of electric cars by 2030.

However, despite the growing stimulus to the production, marketing, and sale of electric and electrified vehicles, it is noted that the tax treatment of the commercial recharging of these vehicles has not received due attention. Before analyzing the possible tax effects of recharges, it is worth clarifying some relevant technical issues about these operations.

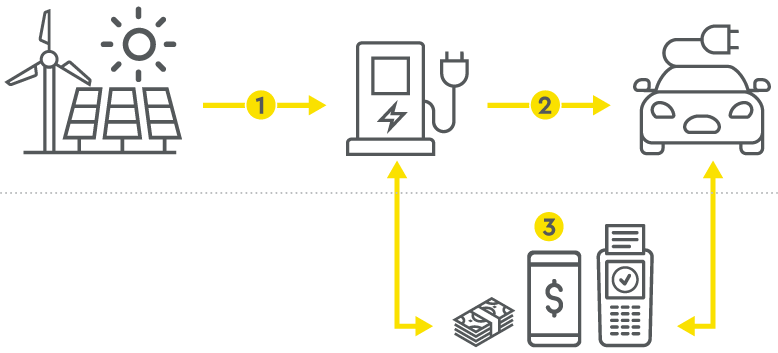

Broadly speaking, the charging process for electric and electrified vehicles follows the following flow:

- The electricity supplier (distributors, in the case of captive consumers of electricity, or generators/traders, in the case of electricity contracted in the Free Contracting Environment - ACL) feeds the load stations with electricity.

- The Charge Point Operator (CPO), commonly called an electric station, offers consumers electric charging from chargers (wallbox or electric pump), with other additional services, such as the possibility of remote station reservation, information about free terminals and charging power, payment methods, etc.

- To facilitate the management of the various issues associated with recharging, the electric station can operate recharges through an e-Mobility Service Provider (eMSP), which brokers recharging - with the management of additional services via the platform - and payment of the recharge. In this situation, the eMSP enters into the contract with the consumer and releases to the consumer the recharge and other service components received from the charging station.

Regarding the remuneration for recharges, the price charged generally consists of a basic fee per charge plus a variable fee per volume (per kWh) or per charge time (per hour or minute). However, it is common for large supermarket chains, shopping centers, and office buildings to also offer free charging of vehicles during the customers' stay, as a form of attraction.

Considering the above scenario, a number of relevant questions arise regarding the tax treatment of electric vehicle recharging activities, which may become even more complex if the eMSP is also involved in the recharging supply process.

In particular, there is a lot of uncertainty regarding the levying of ICMS and ISS on the charging activities of electric vehicles. The uncertainty lies especially in the qualification of the recharging activity as a service, taxable by the ISS, or as a form of electricity trading, taxable by the ICMS.

At first sight, we believe it would be defensible to qualify electric vehicle recharging activities as a service, of which electricity would be an input. This perspective is based on the fact that consumption of the electric energy used for recharging is done by the charging station (which uses this input to provide its recharging service).

In other words, the charging station would act only as a consumer unit of the electricity supplied by the distributor, generator, or trader, and the electricity trading cycle for ICMS purposes would end there.

Supporting this interpretation, the chairman of the National Agency of Electric Energy (Aneel), when approving Aneel Normative Resolution 819/18 - which regulated electric vehicle recharging activities - expressed the understanding that "the recharging of electric vehicles is characterized as a distinct service, which uses electricity as an input.

Although the resolution was revoked by Aneel Normative Resolution 1,000/21, the provisions on electric vehicle recharging activities were maintained in the current resolution, which seems to indicate no change in Aneel's interpretation on the subject.

It would be possible to argue, therefore, that operation of recharging electric vehicles does not represent marketing and sale of a commodity (in this case, electric energy), since it only aims to offer optimized recharging of the vehicle. Electricity is used as an input for a recharging service, not as a commodity in itself.

However, considering the perspective that recharging of vehicles represents a service, the list of services attached to Complementary Law 116/03 is not clear enough as to the qualification of this activity for ISS taxation purposes and the form of taxation (the tax calculation basis).

Specifically as to the form of taxation, we recall that the only item on the list of services attached to Complementary Law 116/03 that refers to the "loading and reloading" of vehicles (item 14.01) excluded the "parts and pieces used" from the municipal tax assessment, which would be subject to the ICMS.

The absence of an express provision on energy (which would not be a part and piece) in the ISS legislation could be considered by the states as permission for the ICMS to be levied on the amount of electricity used in the recharge, even if the recharge activity is considered a service.

However, it seems to us that electric energy could not be considered a part or piece used in the recharging of electric vehicles, since it is not part of the car, much less indivisible from it - so much so that the recharging is consumed integrally with the use of the vehicle.

The very nature of electricity - as the movement of electric charges resulting from the existence of a potential difference between two points - prevents it from assuming the appearance of a part or piece, since it has no material aspect.

Although the value of the energy has already been taxed by the ICMS when it is acquired by the charging station, this same value could be understood as a cost of providing the recharge service and, consequently, included in the calculation basis of the ISS. As the municipal tax legislation did not expressly intend to cover recharging of electric vehicles, there is a risk that the ISS tax basis would be unduly broadened to also include the values of the energy used in recharging.

Even if the charging station is not considered an electricity trader for regulatory purposes, one cannot rule out the possibility that the state treasury departments will consider these operations to be a type of supply of electricity, directly taxable by the ICMS.

Even if the state tax authorities have this claim, it does not seem to us that there is an ICMS taxable basis. Let us explain: when the electric station recharges the vehicle, the recharge value (P) will be priced based on the sum of the amount paid for the electric energy consumed by the recharging point (E) and the remuneration for the service provided (S).

As is known, the value "E" was taxed by the ICMS when the electricity was supplied by the distribution company or when the energy was contracted with the generating/trading company in ACL. With regard to the supply of this energy in the recharge, there is no surcharge on the purchase price of the electricity by the charging station. Thus, there would be no ICMS taxable amount on the energy used in the recharge.

The only remaining controversy regarding any ICMS taxation would be regarding the "S" value, since Complementary Law 87/96 provides in its article 13, paragraph 1, II, that all "other amounts paid, received, or debited" in the context of the paid circulation of goods are integrated into the ICMS tax basis. There is therefore a risk that states would consider the remuneration fee for the recharging service (S) as part of the ICMS tax basis.

However, it does not seem possible to accept the levy of ICMS on the "S" value, since the recent Complementary Law 194/22 - in addition to establishing the essential nature of electricity, fuels, communication services, and public transportation for purposes of defining the applicable ICMS rates - expressly provided for non-assessment of the ICMS on "transmission and distribution services and industry charges related to electricity transactions," as provided for in the new subsection X added to article 3 of Complementary Law 87/96.

Among these services and charges now exempt from the ICMS are included the Tariff for the Use of the Electricity Transmission System (TUST) and the Distribution System Use Tariff (TUSD).[1]

In a systematic and analogical interpretation of the new subsection X added to article 3 of Complementary Law 87/96, the amounts charged for recharging electric vehicles (S) must also be covered by the same device, since they constitute an amount paid in consideration for a service of distribution/supply of electricity by the charging stations.

In addition, Precedent 391 of the Superior Court of Appeals (STJ) provides that "[t]he ICMS is levied on the value of the electricity tariff corresponding to the power demand actually used.” If the charging station represents an electricity consumer unit, ICMS taxation on the electricity consumed could occur only when it is purchased by the charging station, and there is no possibility for subsequent levying of a state tax on the fee charged for the recharging service (S).

Considering the vagueness of the current tax scenario regarding electric vehicle recharging activity, we believe that legislative changes will be necessary to better accommodate these operations, guaranteeing greater legal security to the market players. The sectors related to electrified means of transportation have been speaking out about the lack of a legal framework and infrastructure, according to a recent report in Valor.

It is necessary that the various incentives that have been granted for the industrialization and sale of electric vehicles be accompanied by a better definition in the tax field of the electric vehicle charging activities. Thus, it seems to us that the issue will still be subject to extensive and considerable discussion, until it is sufficiently tackled and settled by the tax authorities.

[1] The inclusion of the Tariff for the Use of the Electricity Transmission System (TUST) and the Electricity Distribution System Use Tariff (TUSD) in the ICMS tax basis is subject to the STJ's Repetitive Topic 986, which is awaiting judgment by the First Section of the Court. With Complementary Law 194/22, however, we believe that this judicial discussion is substantively moot.

- Category: Litigation

The electronic performance of procedural acts has been constantly favored by the legal system not only to adapt procedures to the technological innovations experienced by society, but also to make it an instrument capable of ensuring a fair and satisfactory judicial outcome within the shortest time possible.

The phenomenon began, still incipiently, on May 26, 1999, with the publication of Law 9,800/99, more commonly known as the "Fax Law". This standard allowed - in an innovative way for the time - the use of a facsimile or similar data and image transmission system for the performance of procedural acts.

Shortly thereafter, Law 10,259/01, known as the "Law of Special Civil and Criminal Federal Courts" was enacted, establishing, for the first time, the possibility for courts to organize services for serving parties and receiving petitions electronically.

In order to increase the security of electronic performance of procedural acts in the scope of the special courts, president Fernando Henrique Cardoso promulgated Executive Order 2,200/01, responsible for creating the Brazilian Public Keys Infrastructure (ICP-Brasil). This system was intended to "ensure the authenticity, integrity, and legal validity of documents in electronic form, of the supporting applications, and of the enabled applications that use digital certificates, as well as secure electronic transactions," as stated in the executive order.

Given the great repercussion of the standards in question, several laws were published amending the Code of Civil Procedure of 1973 (CPC/73) to allow the performance of procedural acts electronically. This was the case with Law 11,280/06, which established the possibility for the courts to regulate the practice and communication of electronic procedural acts, and Law 11,341/06, which authorized the presentation of proof of divergence of case law for the purposes of filing special appeals through electronic media.

In this context of growing technological procedural evolution, Law 11,419/06 was published, more commonly known as the "Electronic Procedure Law".

This normative law brought in several innovations to the CPC/73, besides having regulated the performance of several procedural acts electronically, such as the complaint and interlocutory petition. It also authorized the bodies of the Judiciary to develop electronic systems for processing and managing lawsuits through totally or partially digital records, which led to the creation of various digital platforms, such as PJE, e-proc, e-saj, and projudi, among others.

With the publication of Law 13,105/15, the current Code of Civil Procedure (CPC/15) entered into force, giving even more importance to the electronic performance of procedural acts, by providing, for the first time, that the Public Administration (direct and indirect) and public and private companies must keep their records updated in the digital case systems for the purpose of receiving summonses and subpoenas electronically (articles 246, 1,050, and 1,051, CPC/15).

Under the pretext of regulating this registry, Judicial Review Board Resolution 236 was issued (CNJ Resolution 236/16), which established the Platform for Procedural Communications (Electronic Domicile), among other procedures. Given the shallowness of the regulation, however, this system was not adopted in court cases immediately.

After that, Law 14,195/21 was issued, which amended several provisions of CPC/15, especially with regard to the communication of procedural acts. This standard established, among other points, that service of process will preferably be done electronically, reinforcing the obligation of registering the parties for the purposes of receiving summons and subpoenas, raising this registration to the category of a procedural duty (articles 77, VII, 246, head paragraph, CPC/15).

It was also established that, if the electronic summons is not received by the defendant within three business days, it must present in the record, at the first opportunity, justification for not having received the summons, under penalty of answering for contempt against the Judiciary, subject to a fine of up to 5% of the amount in controversy (article 246, head paragraph, paragraphs 1-B and 1-C, CPC/15).

With this, again with the objective of regulating the registration of the parties in the electronic case systems, CNJ Resolution 455/22 was promulgated. This resolution established the Judicial Branch Services Portal and regulated the service of summonses and subpoenas via Electronic Judicial Domicile and the National Electronic Gazette of the Judiciary (DJEN) - the latter already in regular use by the federal courts.

According to information recently released by the CNJ, the Judicial Branch Services Portal and the Electronic Judicial Domicile will finally be implemented on September 30.

According to CNJ Resolution 455/22, the Judicial Branch Services Portal, a digital platform for access by external users, will allow unified consultation of all electronic proceedings in progress, electronic petitioning, and access to summonses and subpoenas received both via Electronic Judicial Domicile and via DJEN. The system promises to standardize the various digital platforms operated by the courts, giving users greater security.

The Electronic Judicial Domicile, in turn, will allow the parties to receive summons and subpoenas electronically, either by e-mail or other digital means of communication they may opt for, such as SMS or instant messaging applications (for example, WhatsApp), unifying the communication channel between the litigants and the Judiciary.

It is important to reinforce that registration is mandatory for the Public Administration (direct and indirect) and for public and private companies, which must register within 90 days from the date of implementation of the Electronic Judicial Domicile, as expressly established by CNJ Resolution 455/22. This requirement is not imposed on individuals, micro-enterprises, and small businesses that have an e-mail address registered in the integrated system of the National Network for the Simplification of Registration and Legalization of Companies and Businesses (Redesim).

Without the registration, the interested party will be subject to procedural sanctions, ranging from possible imposition of a fine in the event of failure to confirm receipt of the electronic summons within the established deadline, to expiration of the deadline to respond to the summons. It will also be subject to the legal consequences associated with its inaction (article 246, head paragraph, paragraphs 1-B and 1-C, CPC/15 and article 20, paragraphs 3 and 4, CNJ Resolution 455/22).

It is essential, therefore, to monitor the implementation of the Electronic Court Domicile and subsequent registration as requested. We are available to assist you with this new measure.

- Category: Labor and employment

The possibility of working from wherever employees want, without limiting themselves to a home base, is currently one of the most desired benefits by employees.

According to research conducted by MBO Partners,[1] the number of North American professionals who adopted work-from-anywhere grew 50% in the first year of the pandemic. The Conference Board estimated that only 8% of jobs were primarily remote in the US before the coronavirus. After that, estimates range from 20% to 50% of jobs.[2]

This change did not happen exclusively in the US. It is a global trend. Various companies have adopted strategies to improve remote working to make it more attractive, healthy, and productive, benefiting both employees and employers. More and more people are rethinking the need to continue living in large cities and working only from one place.

According to Vagas, a Brazilian HR tech recruitment company, the technology, finance, consulting and business management, insurance, telecommunications, and education sectors are the ones that most offer remote work positions in Brazil.

The work-from-anywhere model has allowed a major change in Brazil, as the number of foreign companies, without local subsidiaries/entities in Brazil, engaging Brazilians citizens to work remotely from Brazil has substantially increased over the last three years.

It is becoming common, especially in the tech industry, to have Brazilian individuals engaged directly by foreign companies, receiving in USD, EUR or even in bitcoins, abroad.

But what are the labor and employment risks/issues foreign companies should consider before engaging individuals in Brazil? Do they have to comply with local employment laws?

Firstly, it is important to have in mind that, according to Brazilian laws as well as case law, labor relationships (which include independent contractor relationships) and employment relationships with the provisions of services in Brazil are both subject to Brazilian labor and employment laws and, also, to the jurisdiction of Brazilian labor courts.

The parties cannot agree otherwise and, even if they do so by, for example, agreeing to an arbitration clause or to the application of US law, such contract would be deemed null and void. This is because, according to the Brazilian Federal Constitution, whenever there is a dispute involving the existence of a potential employment relationship between two contracting parties, Brazilian labor courts have jurisdiction to rule the dispute and such ruling must be made in accordance with Brazilian labor and employment laws.

In this context, it is important to have in mind that, although there is no statute prohibiting foreign companies from hiring Brazilian citizens, it is not possible, from a practical perspective, for a foreign company to engage an individual, in Brazil, under an employment relationship, without having a local subsidiary incorporated in Brazil. This is because there are certain obligations that employers must comply with vis-à-vis the Brazilian Government that require the existence of a Brazilian entity.

Due to this, foreign companies hiring individuals in Brazil usually engage them as independent contractors only, without an employment relationship.

In Brazil, independent contractors may be engaged (a) as individual independent contractors or (b) through legal entities incorporated by them (so called “PJs”).

Independent contractors are not entitled to labor and employment benefits (annual vacations and vacation bonus, Christmas Bonus, deposits into the Guarantee Fund for Length of Service (FGTS), benefits established by the applicable collective bargaining agreement, etc.), but solely the remuneration package agreed upon between the parties.

Payments made to independent contractors by foreign companies are also not subject to social security charges in Brazil, as the paying source is not a Brazilian entity.

This is why foreign companies are able to offer remuneration packages much more attractive to Brazilian individuals when compares to Brazilian companies. Not only they usually pay abroad, in USD or EUR, but also they do not collect charges in Brazil.

However, Brazilian laws do not avoid the pronouncement of a direct employment between independent contractors and the contracting company in the event the legal requirements for an employment relationship are found to have been met.

On the contrary: if the independent contractor renders services (i) on a personal basis, (ii) on a regular basis, and (iii) under the subordination/direction of the contracting company’s employees/representatives abroad, an employment relationship must be declared directly between the individual rendering services and the contracting company.

This is based on the general principle of “substance over form”, according to which an employment relationship shall exist directly between the contracting parties, regardless of any agreement entered into between them if all the legal requirements for an employment relationship described above are found to have been met in the case.

In this case, if the independent contractor files a labor lawsuit against the contracting company, it may be required to pay all labor and employment benefits described above, in accordance with Brazilian law. This risk exists regardless of the nature of the contract.

It is true that if the foreign entity does not have a Brazilian legal entity, the chances of materialization of the risks are lower, but they still exist. As there is no Brazilian entity, the independent contractors would have to sue the foreign company, which is time consuming and depends on how long the courts take to rule the case, etc. Even though the risk exists, it would be more difficult to enforce a decision against a foreign company.

The risks increase, however, if the foreign entity decides to incorporate a local entity in Brazil, as it will become liable for all potential past labor and employment liabilities. This is especially relevant for foreign companies plaining to set foot in the Brazilian territory.

Bearing this in mind, foreign companies should map potential risks and address them before engaging individuals in Brazil.

[1] https://s29814.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/MBO-Digital-Nomad-Report-2020-Revised.pdf, accessed on August 30, 2022.

[2] https://vocesa.abril.com.br/sociedade/o-futuro-do-anywhere-office/, accessed on August 30, 2022.

- Category: Real estate

On October 17, the Judicial Review Board of the State of Rio de Janeiro issued CGJ Ordinance 77/22 with the intention of facilitating the disposal of assets of estates before completion of probate, without the need for intervention by the Judiciary.

Under the new rule, it will be possible to sell an estate's assets by public deed, regardless of court authorization. The deed, however, must include and prove the payment, as part of the price, of the full causa mortis transfer tax on the entire inheritance, in addition to prior deposit of the fees due for the extrajudicial probate. In other words, instead of giving this part of the price to the seller, the purchaser will directly discharge these expenses of the estate.

The change aims to facilitate the sale of real estate during out-of-court probate, whether due to urgency on the part of the parties or the heirs' lack of resources to complete the probate process. It is not uncommon for the cost of fees and taxes to prevent the division of the estate or to resort to the courts in the probate process in an attempt to obtain a court order to authorize the sale of part of the estate and thus raise funds to pay for these expenses. The new rule, therefore, can be seen as an important litigation prevention measure.

It is fundamental to note, however, that failure to draw up the public deed of extra-judicial probate within 90 days from the acknowledgement of the prior deposit, unless there is a fully justified reason, will cause the seller to lose the fees deposited by the purchaser in favor of the notary public, since, in this case, the notarial act will be considered effectively performed.

Although the real estate transaction itself is not affected, it is recommended, therefore, that the parties assess the inclusion of a regulation on this subject in the deed of sale and purchase, with possible consequences and penalties if the established deadline is not met, in order to provide greater security for the parties and the transaction.

The property sold will be listed in the estate list for the purposes of determining the emoluments, tax classification, and calculation of the apportionment, but it will not be subject to partition. Its sale will be noted in the probate deed.

This new rule does not apply to disposal of real estate located outside the State of Rio de Janeiro and will also not control in cases where probate cannot be done up by a public deed in an extrajudicial manner and/or where there is an unavailability of assets in relation to one of the heirs or the executor.

The new regulation is an incentive for heirs to proceed with the extrajudicial division of property. At the same time, the rule relieves the Judiciary by stimulating the payment of transmission causa mortis, speeding up the process and benefiting the purchaser, who gains legal security with the regulation of the transaction.