Publications

- Category: Litigation

The Third Panel of the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) rendered, on February, a relevant decision on the Special Appeal nº 1.861.306/SP regarding the impossibility of extending the disregarding of the corporate entity to a minority partner who has never (i) taken part in the management of the company or (ii) demonstrably participated in acts of abuse of legal entity or fraud.

With this decision, the Superior Court of Justice reinforced the subjective criteria that must be adopted in order to grant requests for piercing the corporate veil that affects assets of administrators and partners, understanding that it is not feasible to apply the institute to those who, provenly, have not contributed to the practice of events characterizing abuse of the legal entity.

The case in question involved an action for compensation for moral and material damages, in which, in the course of the enforcement of the judgment, a request for piercing the corporate veil was granted to include all the company’s partners as defendants in the executive proceedings after it was concluded that the dissolution of the company took place irregularly. Later, in light of the death of one of the partners, his heiress was summoned to also join the defendants, and challenged the decision.

The First Chamber for Private Law of the Higher Court of Justice of the State of São Paulo (TJSP) granted the heiress's appeal and excluded her from the enforcement proceeding. According to the opinion of the judging body, the piercing must reach "only the assets of the managing partners or of the ones who have effectively contributed to the practice of abuse or fraud in the use of the legal entity" and, since the deceased shareholder had a minority stake in the company (with only 0.0004% of the company's capital stock) and had no management powers, his personal liability could not be recognized. Consequently, the assets of his heirs should be excluded from the enforcement proceeding.

A special appeal was brought before the Superior Court of Justice against the decision by the Higher Court of Justice of the State of São Paulo (TJSP), in which the plaintiffs of the enforcement proceeding raised, among other arguments, that the court would have breached the provisions of Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code, because the condition of minority partner, without management powers, would not exempt that partner’s liability for the acts performed by the company.

Indeed, after the changes promoted by the Economic Freedom Act (Law No. 13,874/19), the legal provision in question (Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code), in addition to providing more detail on the objective criteria that authorize the piercing of the corporate veil due to "abuse of the legal entity" (i.e., deviation of purpose and confusion of assets), received a new wording. According to the current text, the disregard will be applied so that the effects of certain obligations are extended to the private assets of managers or partners of the legal entity who " directly or indirectly benefited from the abuse." In other words, the legal text in question brought new subjective limits for the application of the institute, restricting its effects to those directly or indirectly benefited by the deviation of purpose or the confusion of assets.

Despite the wording given to the article by the Economic Freedom Act with regard to who have their assets reached, the Third Panel of the Superior Court of Justice, when analyzing the case, upheld the decision rendered by the Higher Court of Justice of the State of São Paulo (TJSP), which is based on a different criterion. It was considered that, although Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code does not provide for any restriction on the liability of minority shareholders indirectly benefited by the practice of acts of abuse of legal entity, it would not be coherent "that partners without management powers which are, in principle, unable to perform acts that constitute abuse of legal entity", could have their personal assets reached. In fact, as pointed out in the judgment, when one is faced with a partner who has no management and administration functions and who did not to contribute[1] for the deviation of purpose or confusion of assets, there is no reason to depart from the principle of the patrimonial autonomy of the legal entity and authorize the piecing of the corporate veil in relation to this partner.

Therefore, it is possible to note that, according to the criteria adopted by the Superior Court of Justice, it would be possible to rule out the personal liability of partners not only by the demonstration, required by law, of the absence of direct or indirect benefit (elements that undoubtedly carry significant subjectivity, especially the "indirect benefit"). Personal liability could also be ruled out by the objective proof that the partner, either due to the relevance of his stake and/or the role played by him in the company, would be unable to perform any of the acts that characterize the abuse of legal entity.

In the exact terms of the decision: "The piercing of the corporate veil, as a rule, should only reach the managing partners or those in relation to which it has been proven to have contributed to the practice of acts characterizing the abuse of legal entity."

The position of the Superior Court of Justice in this case, even if only reinforcing previous understandings on the matter, raises additional questions about the applicable parameters to cases in which the assets of the managing partner are sought to be reached, in light of the new wording given to Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code. In particular, it is important to determine whether the status of managing partner will be enough to have the assets reached, presuming the direct or indirect benefit, or whether it will be necessary to prove the existence of this benefit, to the extent that it is an element expressly provided under Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code.

This question reminds us of the existence of different theories coined by scholars about the piercing of the corporate veil that also contemplate the subjective limits for the application of the institute.

Minor theory (“teoria menor”). There are those who support the minor theory, according to which all partners and administrators must have their personal assets reached, regardless of the assessment of benefit or of the fact that they effectively participated in the management of the company. This is the theory adopted, for example, in consumer matters, under Article 28 of the Brazilian Consumer Protection Code, and, in the context of environmental responsibility, by means of Article 4 of Law No. 9,605/98 – which provides for criminal and administrative sanctions arising from conducts and activities harmful that are to the environment.

Larger theory (“teoria maior”). On the other hand, there is the larger theory, according to which the piercing of the corporate veil is an exceptional measure, which is subdivided into two different groups with regard to the subjective limits of the disregard. While for some it is necessary to prove that the partners and administrators (including managing partners) directly or indirectly benefited from the fraudulent acts, for others it would be sufficient to prove that the partner participates or has participated in the management or administration of the company, to the extent that it had a duty to at least prevent the occurrence of the acts in question.

Considering these theories and sub-theories and the decision commented herein, it is possible to envision an answer to the proposed question: the Superior Court of Justice once again aligned itself with the larger theory of piercing of the corporate veil and, more importantly, reiterated the relevant understanding that not all partners will necessarily be affected by the application of the institute. On the other hand, the decision seems to make it clear that, if the partner was an administrator at the time the acts were perpetrated, there will be a strong presumption in favor of the existence of benefit (direct or indirect), thus applying Article 50 of the Brazilian Civil Code. In any case, it will always be necessary to make an analysis of the factual evidences of the case, seeking proof both on the participation of partners and/or administrators in the acts of abuse of legal entity and on the obtention of direct or indirect benefit from such acts.

[1] Obviously, as pointed out in the judgment, the piercing may reach those who do not have management and administration powers depending on the circumstances; for example, when there is explicit bad faith by collusion with the acts perpetrated.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Interest in the concept of ESG (English acronym for Environmental, Social and Governance – in Portuguese, Environmental, Social and Governance - ASG) has increased year by year as a reflection of the growing participation of investors to project analyses based on these themes. According to the website Google Trends, the term is at the height of its popularity among users of the search site worldwide. Brazil follows a similar trend.[1]

The acronym ESG designates a method of analysis of investments in which, in addition to the traditional variables (risk, return and liquidity), environmental, social and corporate governance aspects and risks are considered in decision making. The adoption of such criteria is a paradigm shift for investment decisions and financial strategy, which incorporate practices traditionally associated with sustainability and social issues.

The way such aspects are incorporated into the investment methodology varies by investor or company. In general, the objective of ESG investments is not to generate impact and a positive social solution, but rather to consider the risks related to such themes and minimize them. For this reason, not every ESG investment can be considered an impact investment.

As its name implies, impact investments are explicitly intended to generate positive results from a social and environmental point of view, in addition to ensuring financial return. They can use ESG criteria cumulatively and complementaryly, and their impacts are often measured and evaluated periodically.[2]

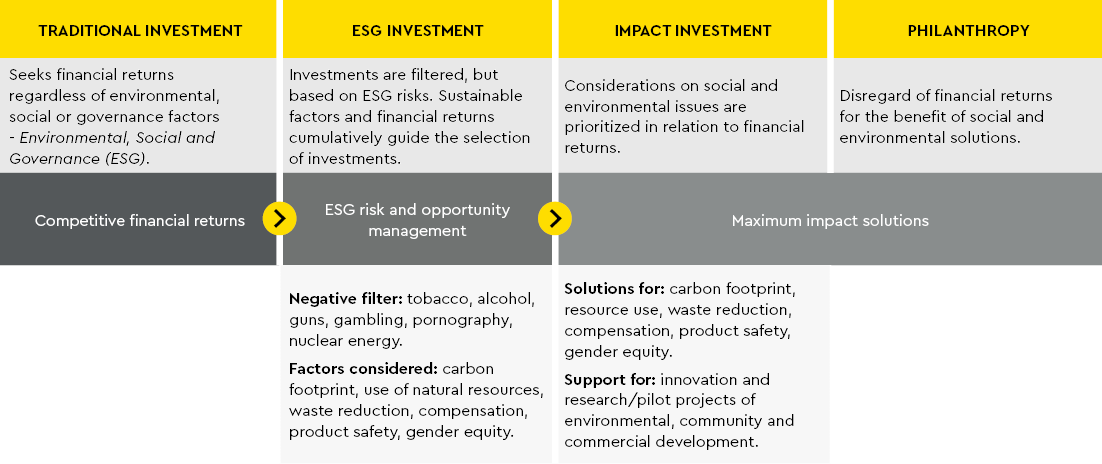

Source: Prepared on the basis of Evolution of an Impact Portfolio: From Implementation to Results, produced by Sonen Capital.

The following diagram simply summarizes different investment structures:

The following table summarises, in a non-exhaustive way, some aspects taken into account in the analysis of an ESG investment:

| ENVIRONMENTAL | Issues related to the preservation, recovery and functioning of the environment and natural resources: ▪ Generation or use of renewable energy sources ▪ Energy efficiency gains ▪ Basic sanitation and waste management |

| SOCIAL | Issues related to the rights and interests of individuals and communities: ▪ Attention to human rights ▪ Enforcement of labor rights and employee relations ▪ Promoting measures to encourage diversity and equal treatment ▪ Relations with local communities ▪ Activities in conflict zones ▪ Health promotion |

| CORPORATE GOVERNANCE | Issues related to the corporate governance of invested companies, other invested entities and their suppliers: ▪ Creation of councils and supervisory bodies ▪ Promoting diversity measures in management frameworks ▪ Disclosure of information ▪ Interactions with related parties ▪ Mechanisms for allocating competences and responsibilities for management ▪ Adoption of ethical standards ▪ Adoption of business strategies that take into account environmental and social criteria ▪ Promotion of best social and environmental and anti-corruption practices internally and externally (with customers and suppliers) |

Source: The emerging financial market verdes in Brazil, Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ).[4]

Financing entities such as development banks (National Bank for Social Development – BNDES, Banco do Nordeste – BNB, among others), multilateral agencies (World Bank, International Finance Corporation – IFC and Inter-American Development Bank – IDB), export credit agencies and commercial banks already include conditions related to ESG aspects in their investment and financing operations. In such cases, the adhering to ESG principles and the obligation to maintain and observe such principles throughout the duration of the funding are usually essential conditions for defining whether the project will receive funding from the bodies concerned. The form and periodicity of monitoring and monitoring of such adement vary according to the funding entity, but many of them have specific departments to do such monitoring.

Companies can also adhere to ESG principles on their own, regardless of the requirement of third parties or funders. In these cases, they seek certifications specific to their activities, their debt securities and/or projects to be financed.

Certifications can be based on various criteria, both environmental and social, and are tied to the issuers and their projects in which the resources will be used. The Green Bonds Principles and the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) are examples of criteria for issuing these certifications for green bonds. Green bonds (or green bonds) are debt securities used by issuers to raise funds for the purpose of implementing or refinancing projects or assets, new or existing, that have positive environmental or climatic attributes (generally defined as green projects) and recognized by a certifying entity.

Based on the Paris Agreement on greenhouse gas emission reduction measures to curb the planet's rising temperature, the CBI proposed common and broad definitions on what should be considered "green" in eight priority sectors in order to standardize and support the growth of a cohesive and consistent global market of green bonds. The sectors are: energy, transportation, water, buildings, land use and marine resources, industry, sewage and waste management, and information technology.[5]

Thus, the CBI created the Certification Scheme of the Climate Bonds Initiative, which establishes the Sector Criteria of the System of Standards and Certification of Climate Bonds, presenting proposals for conditions and eligibility limits that companies and their projects and debt securities must meet in order to be considered green.

Project developer companies can also finance them by issuing encouraged debentures. Law No. 12,431/11 consolidated a privileged tax regime in relation to assets and financial instruments for long-term financing with regard to projects in certain infrastructure and securities sectors that meet some specific requirements.

In relation to the debentures of incentorsins, Law No. 12,431/11 was regulated by Decree No. 8,874/16, which determined that investment projects aimed at the implementation, expansion, maintenance, recovery or modernization of infrastructure projects in the logistics and transportation, urban mobility, energy, telecommunications, broadcasting, basic sanitation and irrigation sectors, as well as projects that provide relevant environmental or social benefits, can be framed as priority projects by the competent ministries for the purpose of issuing such securities.

The encouraged debentures provide some holders with tax benefits for the financing of the project, which, depending on their nature, may or may not be considered green or social and, therefore, subject to environmental and social certifications (such as those of the CBI or Green Bonds Principles) and attract even more investors.

With the increasing support of investors and funders to ESG analyses, the option of obtaining environmental and social certifications should become even more recurrent in project financing structures. In addition, such certifications may be obtained for encouraged debentures in order to increase investor interest in assets that accumulate ESG characteristics and a differentiated financial return.

[1] Google Trends. https://trends.google.com.br/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&q=%2Fm%2F0by114h and https://trends.google.com.br/trends/explore?date=today%205-y&geo=BR&q=%2Fm%2F0by114h . Access on: 10 Mar. 2021.

[2] XP Expert. Impact Investment & ESG: the return of a better world. https://conteudos.xpi.com.br/alternative-week/live/investimento-de-impacto-esg-o-retorno-de-um-mundo-melhor/

[3] Sonen Capital. Evolution of an Impact Portfolio: From Implementation to Results. http://www.sonencapital.com/thought-leadership-posts/evolution-of-an-impact-portfolio/#:~:text=The%20report%2C%20titled%20Evolution%20of,social%20and%20environmental%20impact%20results.

[4] Chalk. The emerging green finance market in Brazil. http://www.labinovacaofinanceira.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/mercado_financasverdes_brasil.pdf

[5] Cbl. Climate Bonds Taxonomy. https://www.climatebonds.net/standard/taxonomy

- Category: Litigation

The Brazilian Arbitration Act was enacted more than two decades ago and had its constitutionality declared incidentally by the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF) in the context of an appeal arising from a proceeding of ratification of a foreign court decision (Case No 5,206, judged in 2001). The analysis of the constitutionality of the Arbitration Act went through the analysis of the constitutional guarantee of non-obviation of judicial jurisdiction. The conclusion was that the Federal Constitution ensure the access to the justice system but at the same time also ensures the right to settle disputes by other mechanisms.

Even though the discussion concerning the constitutionality of the Arbitration Act is already fully overcome, the Court of Appeals of the State of Rio de Janeiro, at the end of 2020, decided to review the issue of non-obviation of judicial jurisdiction to deny the enforceability of an arbitration clause due to the supervenience of a decree of bankruptcy of one of the contracting parties (case records n. 0018212-97.2015.8.19.0209).

The mentioned lawsuit is a contractual review lawsuit with a request for damages filed jointly by Stiebler Arquitetura e Incorporações Ltda. and two specific purpose societies. Whereas the agreement contained an arbitration agreement, the defendants raised that as a preliminary challenge to the lawsuit. The judge granted the request to dismiss the lawsuit since the dispute should be settle by an arbitral tribunal.

However, after Stiebler's bankruptcy decree, the judicial trustee requested that the court of the bankruptcy should be consider the only court to rule on issues involving the bankrupt company. Stiebler, for its part, also argued in its appeal that a company under a bankruptcy regime, which means subject to Law No. 11,101/05, Brazilian Reorganization and Bankruptcy Act, cannot be a party in arbitration proceedings claiming that this would be a breach of the guarantee of non-obviation of judicial jurisdiction.

In addition to analyzing other issues that fall beyond the scope of this article, the Court of Appeals of the State of Rio de Janeiro, more specifically the 3rd Civil Chamber of Rio de Janeiro Court of Appeals, considered that the arbitration clause cannot have unrestricted application and its analysis should consider the high costs that will be borne by the insolvency estate and by the creditors.

Thus, considering that the insolvency estate could not bear to pay for the costs of an arbitration proceeding, the court held that right to access the judicial jurisdiction should be protected and the dispute should remain within the judicial court. This decision was subject to a motion for clarification that was dismissed by the Rio de Janeiro Court of Appeals. Following this, an appeal to the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) was filed by one of the parties to discuss if the arbitration clause remains valid (REsp nº 1959435 / RJ). The appeal was received by the Superior Court in September 2021 and is pending trial.

The decision rendered by the Rio de Janeiro Court of Appeals represents a step backwards to the whole case-law already well- established on the issue. In fact, the STJ itself had already rendered strategic decisions regarding the use of arbitration in the country, also regarding the arbitrability of disputes involving companies going through insolvency proceedings. An example is a decision rendered by Minister Nancy Andrighi in 2008, under Precautionary Measure No. 14,295/SP, which decided on a matter of arbitrability involving a company in out-of- court liquidation. This matter involved ABC Health Services Hospital and Interclinical Health Plan S.A., the Minister rapporteur considered that the arbitration clause remains valid, as it was concluded before the decree of liquidation.

Another example, in Targa vs. Cremer, also judged by the Court of Appeals of the State of Rio de Janeiro in July 2014, lawsuit registered under no. 0016509-16.2014.8.19.0000, Targa turned to the judicial court to request the suspension of an arbitration proceeding claiming that the issues under discussion involved a matter that could not be subject to arbitration because the company was under a reorganization proceeding. The court ruled that since the discussion was substantially contractual, there were no grounds to discuss the lack of arbitral jurisdiction.

Such cases are not isolated and are in line with legislative developments on the subject. First, the II Commercial Law Seminar of the Council of Federal Justice (CJF), held in 2015, approved the 75th statement as it follows: "if there is arbitration agreement, if one of the parties has been declared bankrupt: (...) the judicial trustee cannot refuse the effectiveness of the arbitration clause, given its autonomy in relation to the contract.". Despite this statement had no binding force, it reassured the interpretation given by scholars regarding the matter.

With the enactment of Law No. 14,112/20, the Brazilian Judicial Reorganization and Bankruptcy Act was amended to expressly provide that "the commencement of judicial reorganization proceeding, or the decree of bankruptcy does not authorize the judicial trustee to refuse the enforcement of the arbitration agreement, not preventing or suspending the beginning of the arbitration proceedings" (art. 6, § 9).

This means that the judgment of the 3rd Civil Chamber of the Court of Appeals of Rio de Janeiro, that rejected the enforceability of the arbitration clause, disregarded all recent case-law developments and even legislative changes about the matter.

If the precedent of the 3rd Civil Chamber of the Court of Appeals of Rio de Janeiro is not reviewed – which is apparently a remote hypothesis –, such interpretation will bring legal uncertainty to the arbitration agreements and will imply a real setback in relation to the institute.

There are still problems regarding the compatibility between arbitration and insolvency, however, provided that the matter under discussion is considered arbitrable under Brazilian Arbitration Act, the state and the arbitral jurisdictions can and must live harmoniously. It is expected that when the appeal is judged by the Superior Court, they will maintain its position regarding the binding effect of the arbitration clause, which will be aligned with the legislative developments on the matter.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Alberto Faro, Renata Oliveira and Felipe Baracat

The recently published Law No. 14,112/20, which amends the Judicial Recovery Law, brought innovations on the institute of substantial consolidation, generating some concern for sponsors and funders of infrastructure projects in the modality Project finance.

The consolidation of assets arises in American jurisprudence as a measure of unification of assets and liabilities of companies of the same economic group that are going through an economic and financial crisis, so that all recoverers are responsible for all creditors of the economic group, and that all creditors take the risks of the entire group, and not only their direct debtors.

The U.S. courts then define two determining tests for substantial consolidation, applied in this order, (i) the fact that creditors have negotiated with different companies believing that it is a single economic one; and (ii) the fact that the businesses developed by debtors are characterized by such equity confusion that substantial consolidation would be a beneficial measure for all creditors. The requirements of American jurisprudence are also:

- the presence of consolidated financial statements;

- identity in market performance and corporate composition;

- the existence of cross-guarantees; And

- the existence of a single integrated capital control system.

In any case, substantial consolidation in the form currently configured in the United States represents an exceptional measure and is based on clear legal certainty.

The concern for Project finance in Brazil arises characteristics inherent in this financing model. There are traces such as centralized ownership structure and segregation of projects in several SPEs (specific purpose companies), in addition to the identity of market action between the various companies of the same business group. There are also real guarantees of the projects, and it is common to grant personal guarantees by the parent companies. Cross-guarantees are often also observed.

The concept of substantial consolidation arose with the edition of Law No. 14,112/20, but was already applied by jurisprudence. A not-so-recent decision of the 1st Bankruptcy and Judicial Recovery Court of São Paulo,[1] regarding the judicial recovery process of the Urbplan group, it was the first to establish objective criteria applicable to companies of the same economic group, highlighting: interconnection of companies of the economic group; existence of cross-guarantees; wealth confusion; joint market action; coincidence of directors and corporate composition; relationship of control and/or dependence; and asset diversion.[2] In any case, before the new law, substantial consolidation had already been applied with some degree of legal certainty.

Law No. 14,112/20 innovates by pointing out the institute as an exceptional measure, defining objective requirements for its application. First, and necessarily, when there is "interconnection and confusion between debtors' assets or liabilities" and then cumulatively with at least two other of the following four requirements:

- existence of cross-guarantees;

- relationship of control or dependence;

- full or partial identity of the corporate framework; And

- joint market action among the postulants.

The market concern is related to these requirements, as the structures of the Project finance may have some similarities with such elements.

In any case, the first filter would be impaired: there should not, as a rule, be equity confusion in structured financing operations. This is because each SPE is, in general, the embodiment of an independent enterprise. Creditors are also not expected to negotiate with the same economic group. On the contrary, creditors understand that the contracting of debts with the SPs represents, above all, a protection of their credit, since they assume a risk, previously quantified, specific to the project financed, even if they often have reliable guarantees from shareholders or with the conclusion of an ESA (Equity Support Agreement).

The main difference from more traditional business financing is that the Project finance adopts this structure exactly to allocate risks efficiently and protect creditors within a resource leverage scenario – the creditors of these projects do their risk and credit analysis based on this structure and, consciously, adopt the risks of a given project without the intention of assuming the risk of the business group. The new law also seems to bring greater predictability to the application of the institute in this context, by positively the conditions and requirements for its application and also considering that the jurisprudence has well understood the contractual, corporate and capital structure inherent in this type of financing.

Another important and sensitive innovation for the Project finance substantial consolidation will result in the immediate termination of trust sums and claims held by one debtor in the face of another. This will not, however, impact any lender's real guarantee. That is, if, on the one hand, there are impacts on the credit risk of projects with the potential extinction of the fidejussory guarantees, on the other hand, the law would rule out the possibility of ineffectiveness of real guarantees.

[1] TJ/SP. Case No. 1041383-05.2018.8.26.0100. Processing in the 1st Bankruptcy and Judicial Recoveries Court of the Capital.

[2] Such requirements are not adopted in a unique manner by case law. This is the decision of Judge Daniel Carnio Costa, holder of the 1st Court of Bankruptcies and Judicial Recoveries of São Paulo, a court specialized in the matter of the TJ / SP - today the court of greater relevance in matters of commercial law and whose theses are usually replicated by other courts.

- Category: Tax

The year 2020 will be marked not only by the pandemic, but by the speed with which the organs of public administration have adapted to the new reality of social distancing. The Administrative Council of Tax Appeals (Carf), the body responsible for the trial of federal tax administrative proceedings, also had to adapt to the new non-face-to-face format.

For the council, the year 2020 began with the prospect of a new internal rules, including the possibility of society giving an opinion in the draft following the transparency passed on by Carf, through a public consultation.

However, the placement of a new regiment was in the background, since the pandemic forced the body to concentrate its efforts on maintaining the trial activity in the period of social distancing.

In March, with the stoppage of face-to-face sessions, the Ministry of Economy published Ordinance Carf No. 10,786/20, instituting non-face-to-face trial sessions for administrative processes involving: (i) historical values of up to R$ 1 million; or (ii) matter subject to the summary or resolution of Carf or, furthermore, decisions finalized by the Supreme Court or the Supreme Court given in the system of the general repercussion or repetitive appeals. Until then, the possibility of virtual sessions existed only for the trial of cases below 60 minimum wages, and, in such cases, without the possibility of oral support or participation of interested parties.

For this new trial model, Carf implemented new systems for virtual sessions, enabling oral support or real-time monitoring of judgment. And in order to check the publicity of the trials, the sessions are later made available to the public on YouTube.

Some say that virtual sessions surround the taxpayer's right of defense, claiming that prerogatives concerning trials in face-to-face sessions have been mitigated. However, it seems to us that Carf is trying, to the fullest, to minimize any harm that virtual judgment can bring to taxpayers.

With the implementation of non-face-to-face sessions, the departing of requests for removal of the agenda was made flexible, for later reinclusion when the session resumes in person, being another attempt by the agency to reduce any damage that virtual sessions can bring to the parties. Carf also made it possible to hold virtual hearings, for the order of interested parties with the rapporteur of the administrative procedure, which confirms the commitment of the body to maintain satisfactory judicial provision.

On August 14, 2020, with the reduction of the number of lower-value cases, Carf published Ordinance No. 19,366/20, increasing the amount of jurisdiction to R$ 8 million and allowing several other cases to be brought to trial.

A few months after the establishment of non-face-to-face sessions, the results have already begun to appear. The president of the body, Counselor Adriana Gomes Rêgo, mentioned at the VI Carf Seminar on Tax and Customs Law that, surprisingly, compared to 2019, the year was marked by a significant increase in the number of trials – 55% more in the months of June to October.

The period was also distinguished by the extinction of the quality vote, with the publication of Law No. 13,988/20, which in its art. 28 determines, in case of a tie in the judgment of the tax credit requirement, the solution of the issue in a favorable way to the taxpayer.

After controversial discussions about its applicability and extension, the Ministry of Economy issued Ordinance No. 260/20 to regulate the new provision, clarifying that the extinction of the quality vote would only apply to processes that discuss the requirement of tax credit through infraction notice or notification of release. Under the ordinance, the new provision will not apply to procedural discussions, judgment of declaration embargoes or other kinds of processes within Carf's jurisdiction.

Despite the regulation by the Ministry of Economy, the discussion on the extinction of the quality vote extended to the Supreme Court. Direct actions of unconstitutionality are being filed in the high court questioning the legislative process that resulted in the publication of Law No. 13,988/20. Until the closing of this article, the Supreme Court had not yet ruled on the merits of the issue.

While 2020 was the year of adaptations in the agency, the expectation is that 2021 will be consolidation, maintaining pace and judgment models, at least until a safer phase of the pandemic is reached. Virtual trial sessions, at least until the completion of the national vaccination plan, must follow.

And given the performance figures mentioned here, the agency's promise to continue implementing measures to optimize virtual judgment is already being fulfilled this early in the year.

In January, Ordinance Carf/ME no. 690/21 was published, which raised the amount of jurisdiction for virtual judgment of administrative proceedings to R$ 12 million, in addition to providing for the possibility of judging representations of nullity also virtually.

This increasing increase in jurisdiction values – from R$ 1 million to R$ 8 million and, in 2021, to R$ 12 million – indicates the reduction in the number of lower-value cases and the body's interest in increasing the percentages of trial of cases.

It is not yet known what Carf's next steps will be throughout the year. The resumption of the renewal of the bylaws, after public consultation, is of great interest to taxpayers, who also yearn for a modernisation of the platforms for the transmission of the sessions and the system for monitoring administrative processes itself.

Given the significant increase in the number of judgments in virtual sessions, Carf is expected to establish, definitively, a mixed regime of judgment of administrative processes, granting taxpayers the opportunity to choose the modality of judging their cases.

- Category: Corporate

There is a mutually beneficial and synergetic relationship between non-governmental nonprofit organizations (NGOs) and for-profit companies in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) topics. Not only can nonprofit NGOs adopt good environmental, social and governance practices in the course of their activities, similar to for-profit companies, but for-profit companies can also count on nonprofit NGOs to help them in projects that create positive environmental or social impacts, a true feedback relationship that generates benefits for all parties. It couldn't be any other way. After all, they share similar and compatible purposes and principles. There should therefore be a cross-collaboration between the for-profit and nonprofit entities in advancing the ESG agenda in order to boost value generation.

What is ESG?

The theme of sustainability has always existed in the corporate world, but in a mandatory and less participatory way. Historically, the government borne the main role of promoting sustainability, pressuring companies through the enactment of laws and regulations. Sustainability discussions now take new contours. The corporate world is under pressure from investors (through the allocation of capital in sustainable projects), consumers (through boycotts of unsustainable products), employees (who demand a now look to human capital management and talent acquisition) and society in general. The "stakeholder capitalism" is no longer an investment niche of few organizations concerned with social and environmental issues and now reaches virtually the entire traditional economy. Companies are expected to be actively engaged in solving social and environmental problems.

In this context, the ESG theme has served as an important factor to boost sustainable development – "one that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs".[1]

The ESG approach requires the evaluation of businesses, companies, institutions and even countries not only from an economic point of view, but also according to environmental, social and governance indicators. The corporate environment is evolving; those who resist will be not only on the wrong side of history, but also at a competitive disadvantage.[2] In these new times, consumers and society at large expect much more from businesses. They are not satisfied with companies that seek only profit. Organizations that accept these responsibilities and are able to meet their stakeholders’ expectations will ultimately bring greater benefits to its shareholders.

In addition to contributing to a healthier and fairer ethical society, good ESG practices are related to several benefits, such as risk mitigation, better capacity for innovation and adaptation, cost reduction, good reputation, attracting new generation talent, resilience to adverse scenarios, among others. For these reasons, what was once an issue reserved for activists is now increasingly present in the daily lives of investors and the financial market.

A study by the Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing showed that sustainable funds outnumbered traditional ones and reduced investment risks during the covid-19 pandemic. Although the crisis caused a global recession and huge market volatility in 2020, sustainable funds have achieved better performances than traditional ones. An analysis of 3,000 mutual funds and Exchange Traded Funds - ETF (indexed exchange traded funds) in the United States showed that sustainable funds performed 4.3% above the median of traditional funds in the last year.[3] Also, according to Morgan Stanley, in early 2020, 1 in 3 dollars under professional management in the U.S. was employed in a sustainable investment strategy, totaling approximately $17.1 trillion, up 42 percent since 2018.

Among the metrics most commonly used in the ESG theme, the following stand out:

Environmental

- Proper waste management

- Efficient management of water, clean energy and other resources

- Emission of polluting gases

- Deforestation

- Biodiversity

Social

- Enforcement of labor rights and labor safety

- Talent attraction and retention

- Employee welfare

- Encouraging diversity and gender protection

- Human rights and positive impacts on society

- Data protection and privacy

Governance

- Transparent corporate governance practices

- Compliance and promoting ethical values in the conduct of business

- Composition of the Board of Directors

- Relationship with government entities and politicians

What is the third sector?

The first sector includes the State and its public institutions, the entities of direct and indirect Public Administration, traditionally the main responsible for coping with social and environmental problems. The second sector is the private sector, composed of the private non-governmental initiative, usually companies with the aim of obtaining profit – that is, the market. The third sector is formed by private non-governmental organizations without the objective of profit that perform voluntary activities developed in favor of society and the public at large, independently of the other sectors (government and market), although with them can establish cooperation agreements and partnerships and can receive funding from them.

The third sector is a direct result of the inability of the public authorities to solve certain social and environmental problems, thus making great room for the prominence of civil society. The performance of the third sector promotes an active and participatory civil society, which seeks the public interest and provides better services to the community. In addition, it makes civil society more engaged and interested in participating in state decisions.

Among the best-known non-governmental organizations in the third sector are charities, social organizations, non-profit entities, community funds, foundations, and various types of associations.

How ESG can help the third sector and vice versa

In view of the previous definitions, it is clear that there are common objectives between companies and the third sector in the search for environmentally, socially and governance-sustainable practices.

Several ESG practices developed by private companies can also be used by nonprofit organizations, such as governance, return and impact measurement and efficient capital allocation, to promote greater efficiency in the administration and use of resources. The use of corporate governance mechanisms of for profit companies by the third sector allows to achieve the objectives of:

- Transparency: making clear, true and complete information available to all stakeholders, including sponsors, donors, partners and supported communities;

- Equity: fair treatment of all stakeholders, avoiding discriminatory attitudes or policies, under any pretext;

- Accountability: accounting and measurement of social impacts and project efficiency) by managers (members, directors, executives, tax advisors, auditors); and

- Sustainability: adoption of social and environmental considerations in the definition of programs, projects and operations, with a view to the longevity of the organization.

Similarly, we can imagine several forms of collaboration between nonprofit entities and companies in relation to ESG practices. In this sense, nonprofit organizations can, for example, work together with companies in projects and terms of partnership or consulting, lending the experience and knowledge acquired in the pursuit of their causes, to assist in the supervision and development of ESG performance indicators in the corporate world. This would be the case of an NGO focused on protecting the environment that helps private companies verify the achievement of pollution and deforestation metrics. Or the situation of an entity engaged in the fight against gender inequality that assists private companies in adopting measures to increase the representativeness of women and blacks in their payroll and senior management. Both sides benefit: the NGO, advancing its cause and creating a new source of fundraising and partnerships, and the company, with a more efficient way to monitor its metrics, achieve goals and achieve greater transparency in its commitment to such metrics.

With the increasingly common formation of partnerships and agreements between the State and the organizations of the third sector, the Public Administration ends up having the task of supervising the legal entities of the third sector. Then comes a great opportunity for the managers of these organizations to take advantage of ESG practices to create a robust corporate governance structure that allows the adoption of control mechanisms, and to promote diversity, respect legality and follow principles of social and economic responsibility. This process helps make administration more efficient in order to prevent fraud and corruption, promote transparency, and take better advantage of resources.

Transparency driven by corporate governance can also increase the value of the entity, helping it in its fundraising initiatives and contributing to its own development. The adoption of best practices of corporate governance and sustainable performance from a social and environmental point of view can also inspire more confidence in key donors, giving them more peace of mind that their resources will be employed honestly, efficiently and responsibly.

Companies that adopt the ESG in their business model and their strategic planning have an incentive to promote donations to third sector institutions in order to help them in this cause, in view of their common interest in the environment and sustainability. The positive social and environmental impacts generated by NGOs with the support of private corporate donations ultimately backfeed the system and help companies achieve the sustainability goals required by shareholders, investors and consumers.

[1] Brundtland Report, UN, 1987

[2] Hunt, Vivian, Simpson, Bruce and Yamada, Yuito. The case for stakeholder capitalism, 12/11/2020. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/strategy-and-corporate-finance/our-insights/the-case-for-stakeholder-capitalism

[3] Institute for Sustainable Investing. Sustainable funds outperform peers in 2020 during coronavirus, 24/2/2021. https://www.morganstanley.com/ideas/esg-funds-outperform-peers-coronavirus