- Category: Labor and employment

There is no other subject being talked about than the first debate of the presidential candidates in the 2022 electoral race. The topic is on people's lips and, of course, in virtual chat groups.

In our last article, we addressed the precautions employees and employers should take when using work tools and private social networks to exchange messages, and the consequences they may face when transmitting fake news. It was not for nothing: shortly after publication, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) opened an investigation against members of a virtual chat group precisely because of the content shared.

Fearing something already discussed in the 2018 election - the possibility of businessmen influencing their employees to vote for one candidate or another - the Labor Prosecutor's Office (MPT) this year issued Recommendation 01/2022 to curb certain corporate practices.

According to the agency, companies must refrain from granting (or promising to grant) any benefit in exchange for voting, as well as threatening, embarrassing, or directing people to vote for candidates in the upcoming elections.

The message is clear and ends with a warning: failure to comply with the recommendation will lead the Labor Prosecutor's Office to apply administrative and judicial measures to guarantee individual liberties and the democratic order.

It is important to say that this embarrassment does not have to take place within the gates of the company, nor does it have to be materialized solely by the acts of its officers or CEO. It can happen in the virtual field - in message groups or in posts on social networks - and can be committed by any representative of the company who has a management position, such as managers and coordinators, among other employees who can influence the decision of their subordinates.

Once again, awareness is the appropriate instrument to prevent the conduct. Companies should not ignore the political moment that Brazil is going through and simply close their eyes to the possibility that certain anti-democratic practices may occur among their employees, even if they are disguised as jokes or “pranks".

Information, lectures, and courses can be given to employees so that they avoid unnecessary exposure of the employer and practices considered abusive by the prosecutorial bodies. The companies must also be prepared to deal with any non-compliance of their conduct by employees who do not follow the Labor Prosecutor’s guidelines. To do this, they need to draw up a contingency plan.

The authorities are watching the companies' movements closely. It is therefore essential to guide and monitor employees so that they do not end up engaging in anti-democratic practices during the presidential elections.

- Category: Capital markets

The Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) has the function of regulatory agent of the Brazilian capital market under the terms of Law 6,385/76. In this capacity, the authority is responsible for the regulation, oversight, and imposition of sanctions on issuers, controllers, and administrators of securities, to the entities that are part of the securities distribution system, to the independent auditors, and to other persons that act professionally in the capital market.

Due to the inspection and supervision activities performed by the CVM, a securities markets oversight fee was instituted by law. The taxable event is exercise of the police power legally attributed to the CVM, under the terms of Law 7,940/89, with constitutional support in article 145, subsection II, of the Federal Constitution.

This Law 7,940/89 was recently amended by Law 14,317/22 (originated from the conversion of Executive Order 1,072/21), which modified the oversight fee as follows:

- expanded the list of taxpayers;

- updated the sums charged;

- established a new calculation criterion based on the net equity of the regulated participants;

- created a type of fee resulting from CVM registration activity, in addition to the already existing periodic oversight fee and public offering fee; and

- changed the form of appeal for coercive fines imposed when a CVM order is not complied with.

For the purpose of clarifying the levying and collection of the oversight fee, the CVM disclosed Circular-Letter 1/2022-CVM/SER, on January 14, 2022. The CVM also makes available on its website a series of answers to frequently asked questions, through which it seeks to clarify the taxpayers' main doubts about the levying, collection, and calculation of the oversight fee.

Considering, however, the questions received, especially from investment fund managers, regarding the correct interpretation of Law 14,317/22, the CVM published, on September 20, 2022, Circular-Letter 2/2022/CVM/SIN/SSE, with guidelines on the levying and collection of the oversight fee, directed especially to the sector in which these administrators operate. We highlight the main clarifications provided by the authority:

-

Modalities of the CVM oversight fee

There are three cases for levying the oversight fee for the securities markets (CVM fees):

- CVM registration activity, for which a registration fee will be due;

- periodic inspection activity, for which an annual fee will be due; and

- activity of public offering oversight, for which an offering fee will be due.

-

CVM Fee Payers

The CVM fee payers are the individuals and legal entities listed in article 3 of Law 14,317/22, among which are, with special regard for the investment fund industry:

- individuals and legal entities within the securities distribution system;

- investment funds, regardless of the assets that make up their portfolio;

- administrators of securities portfolios;

- providers of securities bookkeeping and custody services;

- non-resident investors' portfolios (and not directly the investors); and

- offerors of securities in the public offering of securities, subject to registration or exemption from registration by the CVM.

-

Situations, frequency, and conditions for the collection of CVM fees

The situations, frequency, and conditions for the collection of CVM fees are indicated in articles 4 and 5 of Law 14,317/22. We highlight the main points:

Registration Fee

The CVM registration fee will be due upon initial application for registration as a securities market participant or issuance of an equivalent authorizing act, including market participants whose registration is simplified or automatic, as long as they are regulated by the CVM.

This fee must be paid in full, regardless of the date of the initial registration application or equivalent act, and therefore pro rata payment is not allowed.

As a general rule, the registration fee will be due within 30 calendar days of the registration request. The CVM advised to pay within this deadline, even if the payment notice issued on the CVM website has a different due date.

The regulator explained that it was not possible to customize the system used to issue the payment notice to allow correct setting of the due date. It advised that it is the participant's responsibility to keep track of the deadline.

The CVM made a point of clarifying again, as it had already done in its answers to frequently asked questions, that the registration fee is different from the annual fee. The former is not an advance, even if partial, of the payment of the latter. This point raised doubt since the registration fee consists of 25% of the annual fee applicable to the regulated participant. This, however, does not mean that it is an advance; it only refers to the way of calculating the amount due as a registration fee.

Annual Fee

This fee will be due annually and must be paid in full considering the entire year to which it refers, with pro rata payment not being admitted.

The CVM's annual fee is now due from the date of registration with the CVM until the request for cancellation or suspension is granted, even if the taxpayer is not performing activities or has had its registration suspended by an administrative act of the CVM.

Law 14,317/22 contains a table in its Annex I with the ranges of amounts owed by legal entities for the annual fee. The calculation criterion used is the taxpayers' net equity, except in relation to independent auditors, whose criterion is the number of establishments, according to Annex III of the standard. For individuals, the fees are fixed and are listed in Annex II of the law.

- Investment Funds:

The annual fee for the oversight of investment funds has some specifics:

- Investment funds with asset separation between classes/subclasses:

If the units of the fund are divided into classes or sub-classes for the purposes of calculating the annual fee the sum of the amounts calculated according to the net equity of each class or sub-class should be considered, observing the parameters established in Annex I of Law 14,317/22.

The CVM clarified that this form of calculation provided in the law already considers the new structure of investment funds with mandatory separation of equity between classes and subclasses, whose regulation is still being discussed in the scope of Public Hearing SDM 08/20, which intends to change the rules for investment funds, regulated by CVM Instruction 555 and the standardized and non-standardized Receivables Investment Funds (FIDCs), regulated by CVM Instruction 356 and CVM Instruction 444.

The public hearing has already been subject to comments by market participants and, according to the CVM's Regulatory Agenda 2022, the standard should be issued this year.

- Investment funds with a single class:

In relation to single class funds, for the purposes of calculating the annual fee, the fund's net equity should be considered, observing the parameters set forth in Annex I of Law 14,317/22.

- Method of calculation of the annual fee:

The value of the net equity of the investment funds for the purpose of determining the annual fee should be calculated as follows:

- by the arithmetic average of the daily net assets ascertained in the first four months of the calendar year (i.e. January to April) for funds with daily calculation; or

- based on the value calculated on the last business day of the first four-month period of the year (that is, the last business day of April) for those who have not calculated their net equity on a daily basis.

In view of the rule set out above, the CVM clarified in Circular-Letter 2/2022/CVM/SIN/SSE that the annual fee will only apply to funds that have been created by the end of April of each year and are operating during this first four-month period.

There will be no annual fee for investment funds created after the beginning of May of each year. In this case, the annual fee will be due as of the next calendar year.

If the fund is created at any time after the beginning of May and ends up being closed in the same year, there will also be no levying of the annual fee.

If the fund is created or closed during the first four months of the year, however, the calculation of the annual fee should consider the arithmetic average of the net equity in the period in which the fund operated within that four-month period.

- Investment funds with net equity or zero equity:

The authority clarified that the investment funds registered with the CVM that have zero or negative net equity during the entire first four months of the year must pay the annual fee at the lowest value of the table in which they fit. This means that pre-operational investment funds are also required to pay the annual fee, at the lower amount provided for in Annex I of Law 14,317/22.

- Investment funds that are closing down their activities:

As a general rule, the annual fee will be due up to the closing date of the fund's registration with the CVM, calculated in the ways set out above.

The CVM has clarified how taxpayers should proceed when faced with two exceptional situations related to the liquidation of investment funds:

- in extraordinary liquidation attributed to some external factor caused by a third party (such as liquidation order by the CVM or resignation or extrajudicial liquidation of the fund administrator without replacement), a new annual fee will not be due if the forced liquidation extends into the following year;

- in ordinary liquidation ordered by unitholders, whether by total redemption of the units or by resolution in a meeting, the annual fee for the following year will be due, if the liquidation extends into the next calendar year.

Offering Fee

The CVM offering fee will be due on the occasion of a public offering of securities, including cases of exemption from registration by the CVM, and will be calculated based on the total value of the transaction.

Regarding the public offering of investment fund units, the offering fee must be collected:

- in the case of public offerings subject to registration with the CVM, when filing the registration request; and

- in the case of public offerings with restricted placement efforts that benefit from an automatic waiver of registration with the CVM, by the closing date of the public offering. As stated by the authority, this date may be the settlement date, but not necessarily, since it may be some later date if the structure of the offering provides for the fulfillment of steps related to the completion of the offering after the liquidation date.

If the public offering is done concomitantly with the issuer's initial application for registration with the CVM - including for investment funds - there will be no registration fee, only the offering fee. In other words, there can be no double charging of the CVM oversight fee in this situation.

The offer rate corresponds to a 0.03% rate over the total value of the transaction, observing the minimum rate of R$ 809.16 (that is, transactions under R$ 2,697,200.00 must pay the minimum amount). There is no longer a maximum ceiling for the offering rate.

In public offerings, the total value of the transaction for purposes of calculating the registration fee must cover the base lot, the additional lot, and the supplementary lot, if any. In case of a bookbuilding procedure, the ceiling value of the issue must be considered.

In restricted offerings, the total value of the transaction for the purposes of calculating the registration fee will be the total amount effectively raised, as reported in the closing notice. In this notice, the reference number of the payment of the offering fee that has been made at the closing of the offering must be filled out for information to the CVM.

It is important to note that the concept of the closing of the offering, for the purposes of payment of the registration fee, is not necessarily confused with the date of sending the closing notice.

The offering fee is not charged for public offerings:

- of shares owned by the Federal Government, states, Federal District, and municipalities and other Public Administration entities, which cumulatively: do not seek placement with the public in general and are held in an auction organized by an entity managing an organized market, under the terms of Law 8,666/93;

- of a single, indivisible lot of securities; or

- of Audiovisual Investment Certificates.

The CVM guidelines in Circular-Letter 2/2022/CVM/SIN/SSE are timely and useful to clarify unclear areas, especially regarding the assumptions of levying and form of calculation of the CVM fees that must be collected by administrators of investment funds at the time of registration of issuers, periodically for the funds under management and for the administrator itself and its employees accredited with the CVM, and in conducting public offerings of units.

This is a subject with material economic implications, since any errors that lead to under calculation of the amounts due or delays may generate interest and a late payment fine, in addition to legal charges, under the terms of article 5, paragraph 1, of Law 7,940/89 , which is obviously undesirable.

We remain at your disposal for any further clarifications on this subject.

- Category: Labor and employment

Published on September 5, Law 14,442/22 substantially amended the rules on food allowances and remote work.

The new law clarifies that the amounts paid by the employer as food allowance, provided for in paragraph 2 of article 457 of the Brazilian Labor Law (“CLT”), must be used for the payment of meals in restaurants and similar establishments or for the purchase of foodstuffs in commercial establishments.

The concept of food allowance encompasses both food vouchers and meal vouchers.

Regarding the hiring by employers of a legal entity to provide the food allowance, the legislation now states that the employer cannot demand or receive:

- any kind of discount or imposition of discounts on the contracted value;

- onlending or payment terms that denature the prepaid nature of the amounts to be made available to the employees; and

- other amounts and benefits not directly related to promotion of the employee's health and food safety in the contracts executed with companies that issue food allowance payment instruments.

The prohibitions on the relationship between the employer and the companies that provide the food allowance established by the law do not apply to contracts for the provision of food allowances in effect until their termination or until the period of 14 months has elapsed from the date of publication of the law (November 5, 2023), whichever occurs first. It is forbidden to extend a contract for the provision of a food allowance that does not comply with these prohibitions.

The new legislation establishes a fine ranging from R$5,000 to R$50,000, applied in double in the event of recurrence or obstruction against inspection, inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the food allowance by the employers or companies that issue the instruments for payment of the food allowance.

The establishments that sell products not related to employee nutrition and the companies that accredited them are also subject to a fine. The criteria and parameters for calculating the fine will be subject to an act by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security.

From a tax standpoint, the new legislation amends the provisions of Law 6,321/76, which deals with deduction from taxable income for corporate income tax purposes, to establish that corporate entities may deduct from taxable income, for corporate income tax purposes, twice the expenses proven to have been incurred during the base period in worker food programs previously approved by the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, in the manner and limits set forth by the decree that regulates the matter.

The new law also establishes that expenses allocated to worker food programs (so called “PAT”) must cover exclusively payment of meals in restaurants and similar establishments and acquisition of foodstuffs in commercial establishments.

Law 14,442/22 reproduces in Law 6,321/76 the prohibitions on the relationship between the employer and the companies that provide food allowances (such as prohibition on any kind of discount on the contracted value). The prohibitions will be in effect as defined in the regulations for the worker food programs.

The new legislation also provides that food payment services contracted to carry out food programs must observe the following additional rules:

- placement into operation by means of closed or open payment arrangements, and companies organized in the form of closed payment arrangements, must allow interoperability among themselves and with open arrangements, indistinctively, to share the accredited network of commercial establishments, as of May 1, 2023, it is worth noting that operation of open arrangements is allowed as of now. 2023 is the date as of which the sharing of accredited networks will be mandatory, always respecting the commercial conditions established; and

- free portability of the service upon express request of the worker, in addition to other rules set forth in a decree from the Executive Branch, as of May 1, 2023.

In relation to the penalties applicable in the event of inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the worker food programs by the beneficiary legal entities or companies registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, the new legislation introduces a provision in Law 6,321/76 that establishes the same fine mentioned above, in the same terms.

Furthermore, it establishes as a penalty the cancellation of registration of the beneficiary legal entity or registration of companies linked to the worker food programs registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security, as of the date of the first cancellable irregularity and, consequently, loss of the tax incentive of the beneficiary legal entity.

If the registration of the beneficiary legal entity or registration of the companies linked to the worker food programs registered with the Ministry of Labor and Social Security is cancelled, a new enrollment or registration with the same ministry can only be requested after the deadline to be defined in regulations.

It is important to explain that the penalties established by Law 14,442/22 as a result of inadequate execution, deviation, or distortion of the purposes of the food allowance by employers or companies that issue instruments for payment of the food allowance are applicable to all companies, regardless of whether they are enrolled in food programs, with the exception, of course, of cancellation of the registration of the legal entity in food programs, applicable only if the company is enrolled in a food program.

Due to the changes introduced, companies must reevaluate their food allowance programs to adapt them to the new rules, both from the labor/employment perspective and from the tax and regulatory perspective, especially companies that adopt flexible benefits policies.

In addition to the changes regarding the food allowance, Law 14,442/22 also introduced changes regarding remote work. We addressed this topic in another article, available through this link.

Machado Meyer Advogados will continue to monitor the evolution of the matter and its potential developments. Keep up with our publications by subscribing to our newsletter.

- Category: Tax

Executive Order 1,137, published on February 21 of this year, introduced a zero rate for withholding income tax (IRRF) on income paid to foreign investors. The goal is to attract foreign credit and encourage the issuance of private debt securities.

After republished in an extra edition of the Official Gazette of the Federal Government on the same date, MP 1,137 also changed the legal regime applicable to foreign investment, regulated by CMN Resolution 4,373, in equity investment funds (FIP), among others.

The MP incorporates some provisions that were being discussed in Congress in the scope of Bill 4,188, the substitute of which had already been approved by the House of Representatives in June of this year and became known as the Legal Framework of Guarantees.

The measure takes effect January 1, 2023, and must be converted into law within 60 days, extendable for another 60 days.

Main changes

| Change | Requirements and conditions - who can benefit |

|

The previous rules regarding the composition of FIP's portfolio (minimum limit of 67% of shares of joint stock companies, convertible debentures, subscription warrants, and debt securities in a percentage greater than 5% of the net equity) have been revoked.[1] There is compatibility and alignment with the rules of the Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil (CVM). The restriction on applying the zero tax rate to foreign investors who hold more than 40% of the FIP’s units was also revoked. Expansion of the benefit to: · foreign investors who are shareholders in FIP-IE and FIP-PD&I; and · sovereign wealth funds.[2] Important: expansion of the restriction on the application of the zero tax rate for investors domiciled in a tax-favored jurisdiction to beneficiaries of a privileged tax regime[3] (except sovereign wealth funds). |

· securities subject to public distribution, issued by private legal entities, excluding financial institutions;[4] · FIDC whose originator or grantor of the credit rights portfolio is not a financial institution and other institutions authorized to operate by the Central Bank of Brazil; · financial notes; and · investment funds that invest exclusively in: - securities mentioned above; - federal government securities; - assets producing exempt income referred to in the MP; and - repo operations backed by federal public securities or units of investment funds that invest in federal public securities. *The MP defines income as "any amounts that constitute remuneration of invested capital, including that produced by variable income securities, such as interest, premiums, commissions, bonuses, and discounts, and positive results from investments in investment funds.” |

· The securities must be registered in a registration system authorized by the Central Bank of Brazil or by the CVM. · FIDCs and CRIs can have as objective the acquisition of receivables from only one assignor or debtor. · The FIDC units must be admitted for trading in an organized securities market or registered in a registration system authorized by the Central Bank of Brazil or by the CVM. Exceptions: transactions entered into between related parties[5] and an investor domiciled in a tax-favored jurisdiction or beneficiary of a privileged tax regime do not qualify for the 0% tax rate (except in the case of a sovereign wealth fund). |

[1] Repeal also applicable to the general regime for investments in FIP (15% tax rate).

[2] Foreign investment vehicles whose assets are composed exclusively of funds derived from the sovereign savings of the respective country.

[3] As per IN 1,037/2010.

[4] The following are considered to be financial institutions: banks of any kind; credit cooperatives; savings banks; securities distribution companies; foreign exchange and securities brokerage companies; credit, financing, and investment companies; real estate credit companies; and leasing companies.

[5] As defined in subsections I to VI and VIII of the head paragraph of article 23 of Law No. 9,430/96.

- Category: Tax

In recent years, incentives for electric and electrified vehicles, such as hybrids and plug-ins, have become increasingly common. This is because these vehicles are seen as a way to tackle the climate crisis by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

In the state of São Paulo, for example, the Pro Green Vehicle program, created in March of 2022, aims to encourage the development of industrial companies assembling less polluting motor vehicles through the immediate monetization of accumulated ICMS credits. For commercial companies of this type of vehicle, the São Paulo state government reduced the ICMS tax levied on the marketing and sale of trucks, buses, and electric and electrified vehicles from 18% to 14.5% as of January of this year.

The market for electric and electrified vehicles is tending to become even more consolidated, as pointed out in the report by the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which estimates an almost 500% growth in the production of electric cars by 2030.

However, despite the growing stimulus to the production, marketing, and sale of electric and electrified vehicles, it is noted that the tax treatment of the commercial recharging of these vehicles has not received due attention. Before analyzing the possible tax effects of recharges, it is worth clarifying some relevant technical issues about these operations.

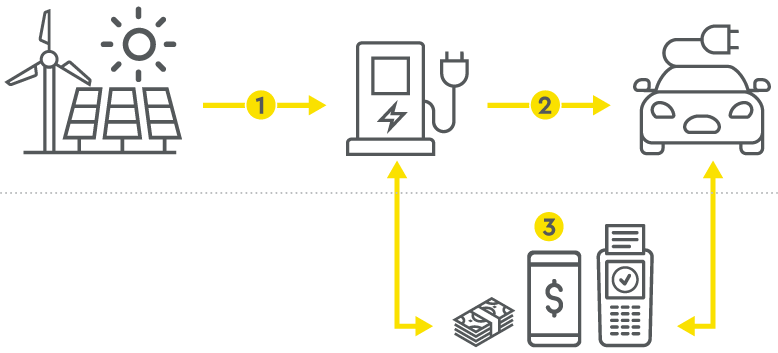

Broadly speaking, the charging process for electric and electrified vehicles follows the following flow:

- The electricity supplier (distributors, in the case of captive consumers of electricity, or generators/traders, in the case of electricity contracted in the Free Contracting Environment - ACL) feeds the load stations with electricity.

- The Charge Point Operator (CPO), commonly called an electric station, offers consumers electric charging from chargers (wallbox or electric pump), with other additional services, such as the possibility of remote station reservation, information about free terminals and charging power, payment methods, etc.

- To facilitate the management of the various issues associated with recharging, the electric station can operate recharges through an e-Mobility Service Provider (eMSP), which brokers recharging - with the management of additional services via the platform - and payment of the recharge. In this situation, the eMSP enters into the contract with the consumer and releases to the consumer the recharge and other service components received from the charging station.

Regarding the remuneration for recharges, the price charged generally consists of a basic fee per charge plus a variable fee per volume (per kWh) or per charge time (per hour or minute). However, it is common for large supermarket chains, shopping centers, and office buildings to also offer free charging of vehicles during the customers' stay, as a form of attraction.

Considering the above scenario, a number of relevant questions arise regarding the tax treatment of electric vehicle recharging activities, which may become even more complex if the eMSP is also involved in the recharging supply process.

In particular, there is a lot of uncertainty regarding the levying of ICMS and ISS on the charging activities of electric vehicles. The uncertainty lies especially in the qualification of the recharging activity as a service, taxable by the ISS, or as a form of electricity trading, taxable by the ICMS.

At first sight, we believe it would be defensible to qualify electric vehicle recharging activities as a service, of which electricity would be an input. This perspective is based on the fact that consumption of the electric energy used for recharging is done by the charging station (which uses this input to provide its recharging service).

In other words, the charging station would act only as a consumer unit of the electricity supplied by the distributor, generator, or trader, and the electricity trading cycle for ICMS purposes would end there.

Supporting this interpretation, the chairman of the National Agency of Electric Energy (Aneel), when approving Aneel Normative Resolution 819/18 - which regulated electric vehicle recharging activities - expressed the understanding that "the recharging of electric vehicles is characterized as a distinct service, which uses electricity as an input.

Although the resolution was revoked by Aneel Normative Resolution 1,000/21, the provisions on electric vehicle recharging activities were maintained in the current resolution, which seems to indicate no change in Aneel's interpretation on the subject.

It would be possible to argue, therefore, that operation of recharging electric vehicles does not represent marketing and sale of a commodity (in this case, electric energy), since it only aims to offer optimized recharging of the vehicle. Electricity is used as an input for a recharging service, not as a commodity in itself.

However, considering the perspective that recharging of vehicles represents a service, the list of services attached to Complementary Law 116/03 is not clear enough as to the qualification of this activity for ISS taxation purposes and the form of taxation (the tax calculation basis).

Specifically as to the form of taxation, we recall that the only item on the list of services attached to Complementary Law 116/03 that refers to the "loading and reloading" of vehicles (item 14.01) excluded the "parts and pieces used" from the municipal tax assessment, which would be subject to the ICMS.

The absence of an express provision on energy (which would not be a part and piece) in the ISS legislation could be considered by the states as permission for the ICMS to be levied on the amount of electricity used in the recharge, even if the recharge activity is considered a service.

However, it seems to us that electric energy could not be considered a part or piece used in the recharging of electric vehicles, since it is not part of the car, much less indivisible from it - so much so that the recharging is consumed integrally with the use of the vehicle.

The very nature of electricity - as the movement of electric charges resulting from the existence of a potential difference between two points - prevents it from assuming the appearance of a part or piece, since it has no material aspect.

Although the value of the energy has already been taxed by the ICMS when it is acquired by the charging station, this same value could be understood as a cost of providing the recharge service and, consequently, included in the calculation basis of the ISS. As the municipal tax legislation did not expressly intend to cover recharging of electric vehicles, there is a risk that the ISS tax basis would be unduly broadened to also include the values of the energy used in recharging.

Even if the charging station is not considered an electricity trader for regulatory purposes, one cannot rule out the possibility that the state treasury departments will consider these operations to be a type of supply of electricity, directly taxable by the ICMS.

Even if the state tax authorities have this claim, it does not seem to us that there is an ICMS taxable basis. Let us explain: when the electric station recharges the vehicle, the recharge value (P) will be priced based on the sum of the amount paid for the electric energy consumed by the recharging point (E) and the remuneration for the service provided (S).

As is known, the value "E" was taxed by the ICMS when the electricity was supplied by the distribution company or when the energy was contracted with the generating/trading company in ACL. With regard to the supply of this energy in the recharge, there is no surcharge on the purchase price of the electricity by the charging station. Thus, there would be no ICMS taxable amount on the energy used in the recharge.

The only remaining controversy regarding any ICMS taxation would be regarding the "S" value, since Complementary Law 87/96 provides in its article 13, paragraph 1, II, that all "other amounts paid, received, or debited" in the context of the paid circulation of goods are integrated into the ICMS tax basis. There is therefore a risk that states would consider the remuneration fee for the recharging service (S) as part of the ICMS tax basis.

However, it does not seem possible to accept the levy of ICMS on the "S" value, since the recent Complementary Law 194/22 - in addition to establishing the essential nature of electricity, fuels, communication services, and public transportation for purposes of defining the applicable ICMS rates - expressly provided for non-assessment of the ICMS on "transmission and distribution services and industry charges related to electricity transactions," as provided for in the new subsection X added to article 3 of Complementary Law 87/96.

Among these services and charges now exempt from the ICMS are included the Tariff for the Use of the Electricity Transmission System (TUST) and the Distribution System Use Tariff (TUSD).[1]

In a systematic and analogical interpretation of the new subsection X added to article 3 of Complementary Law 87/96, the amounts charged for recharging electric vehicles (S) must also be covered by the same device, since they constitute an amount paid in consideration for a service of distribution/supply of electricity by the charging stations.

In addition, Precedent 391 of the Superior Court of Appeals (STJ) provides that "[t]he ICMS is levied on the value of the electricity tariff corresponding to the power demand actually used.” If the charging station represents an electricity consumer unit, ICMS taxation on the electricity consumed could occur only when it is purchased by the charging station, and there is no possibility for subsequent levying of a state tax on the fee charged for the recharging service (S).

Considering the vagueness of the current tax scenario regarding electric vehicle recharging activity, we believe that legislative changes will be necessary to better accommodate these operations, guaranteeing greater legal security to the market players. The sectors related to electrified means of transportation have been speaking out about the lack of a legal framework and infrastructure, according to a recent report in Valor.

It is necessary that the various incentives that have been granted for the industrialization and sale of electric vehicles be accompanied by a better definition in the tax field of the electric vehicle charging activities. Thus, it seems to us that the issue will still be subject to extensive and considerable discussion, until it is sufficiently tackled and settled by the tax authorities.

[1] The inclusion of the Tariff for the Use of the Electricity Transmission System (TUST) and the Electricity Distribution System Use Tariff (TUSD) in the ICMS tax basis is subject to the STJ's Repetitive Topic 986, which is awaiting judgment by the First Section of the Court. With Complementary Law 194/22, however, we believe that this judicial discussion is substantively moot.

- Category: Litigation

The electronic performance of procedural acts has been constantly favored by the legal system not only to adapt procedures to the technological innovations experienced by society, but also to make it an instrument capable of ensuring a fair and satisfactory judicial outcome within the shortest time possible.

The phenomenon began, still incipiently, on May 26, 1999, with the publication of Law 9,800/99, more commonly known as the "Fax Law". This standard allowed - in an innovative way for the time - the use of a facsimile or similar data and image transmission system for the performance of procedural acts.

Shortly thereafter, Law 10,259/01, known as the "Law of Special Civil and Criminal Federal Courts" was enacted, establishing, for the first time, the possibility for courts to organize services for serving parties and receiving petitions electronically.

In order to increase the security of electronic performance of procedural acts in the scope of the special courts, president Fernando Henrique Cardoso promulgated Executive Order 2,200/01, responsible for creating the Brazilian Public Keys Infrastructure (ICP-Brasil). This system was intended to "ensure the authenticity, integrity, and legal validity of documents in electronic form, of the supporting applications, and of the enabled applications that use digital certificates, as well as secure electronic transactions," as stated in the executive order.

Given the great repercussion of the standards in question, several laws were published amending the Code of Civil Procedure of 1973 (CPC/73) to allow the performance of procedural acts electronically. This was the case with Law 11,280/06, which established the possibility for the courts to regulate the practice and communication of electronic procedural acts, and Law 11,341/06, which authorized the presentation of proof of divergence of case law for the purposes of filing special appeals through electronic media.

In this context of growing technological procedural evolution, Law 11,419/06 was published, more commonly known as the "Electronic Procedure Law".

This normative law brought in several innovations to the CPC/73, besides having regulated the performance of several procedural acts electronically, such as the complaint and interlocutory petition. It also authorized the bodies of the Judiciary to develop electronic systems for processing and managing lawsuits through totally or partially digital records, which led to the creation of various digital platforms, such as PJE, e-proc, e-saj, and projudi, among others.

With the publication of Law 13,105/15, the current Code of Civil Procedure (CPC/15) entered into force, giving even more importance to the electronic performance of procedural acts, by providing, for the first time, that the Public Administration (direct and indirect) and public and private companies must keep their records updated in the digital case systems for the purpose of receiving summonses and subpoenas electronically (articles 246, 1,050, and 1,051, CPC/15).

Under the pretext of regulating this registry, Judicial Review Board Resolution 236 was issued (CNJ Resolution 236/16), which established the Platform for Procedural Communications (Electronic Domicile), among other procedures. Given the shallowness of the regulation, however, this system was not adopted in court cases immediately.

After that, Law 14,195/21 was issued, which amended several provisions of CPC/15, especially with regard to the communication of procedural acts. This standard established, among other points, that service of process will preferably be done electronically, reinforcing the obligation of registering the parties for the purposes of receiving summons and subpoenas, raising this registration to the category of a procedural duty (articles 77, VII, 246, head paragraph, CPC/15).

It was also established that, if the electronic summons is not received by the defendant within three business days, it must present in the record, at the first opportunity, justification for not having received the summons, under penalty of answering for contempt against the Judiciary, subject to a fine of up to 5% of the amount in controversy (article 246, head paragraph, paragraphs 1-B and 1-C, CPC/15).

With this, again with the objective of regulating the registration of the parties in the electronic case systems, CNJ Resolution 455/22 was promulgated. This resolution established the Judicial Branch Services Portal and regulated the service of summonses and subpoenas via Electronic Judicial Domicile and the National Electronic Gazette of the Judiciary (DJEN) - the latter already in regular use by the federal courts.

According to information recently released by the CNJ, the Judicial Branch Services Portal and the Electronic Judicial Domicile will finally be implemented on September 30.

According to CNJ Resolution 455/22, the Judicial Branch Services Portal, a digital platform for access by external users, will allow unified consultation of all electronic proceedings in progress, electronic petitioning, and access to summonses and subpoenas received both via Electronic Judicial Domicile and via DJEN. The system promises to standardize the various digital platforms operated by the courts, giving users greater security.

The Electronic Judicial Domicile, in turn, will allow the parties to receive summons and subpoenas electronically, either by e-mail or other digital means of communication they may opt for, such as SMS or instant messaging applications (for example, WhatsApp), unifying the communication channel between the litigants and the Judiciary.

It is important to reinforce that registration is mandatory for the Public Administration (direct and indirect) and for public and private companies, which must register within 90 days from the date of implementation of the Electronic Judicial Domicile, as expressly established by CNJ Resolution 455/22. This requirement is not imposed on individuals, micro-enterprises, and small businesses that have an e-mail address registered in the integrated system of the National Network for the Simplification of Registration and Legalization of Companies and Businesses (Redesim).

Without the registration, the interested party will be subject to procedural sanctions, ranging from possible imposition of a fine in the event of failure to confirm receipt of the electronic summons within the established deadline, to expiration of the deadline to respond to the summons. It will also be subject to the legal consequences associated with its inaction (article 246, head paragraph, paragraphs 1-B and 1-C, CPC/15 and article 20, paragraphs 3 and 4, CNJ Resolution 455/22).

It is essential, therefore, to monitor the implementation of the Electronic Court Domicile and subsequent registration as requested. We are available to assist you with this new measure.

- Category: Labor and employment

The possibility of working from wherever employees want, without limiting themselves to a home base, is currently one of the most desired benefits by employees.

According to research conducted by MBO Partners,[1] the number of North American professionals who adopted work-from-anywhere grew 50% in the first year of the pandemic. The Conference Board estimated that only 8% of jobs were primarily remote in the US before the coronavirus. After that, estimates range from 20% to 50% of jobs.[2]

This change did not happen exclusively in the US. It is a global trend. Various companies have adopted strategies to improve remote working to make it more attractive, healthy, and productive, benefiting both employees and employers. More and more people are rethinking the need to continue living in large cities and working only from one place.

According to Vagas, a Brazilian HR tech recruitment company, the technology, finance, consulting and business management, insurance, telecommunications, and education sectors are the ones that most offer remote work positions in Brazil.

The work-from-anywhere model has allowed a major change in Brazil, as the number of foreign companies, without local subsidiaries/entities in Brazil, engaging Brazilians citizens to work remotely from Brazil has substantially increased over the last three years.

It is becoming common, especially in the tech industry, to have Brazilian individuals engaged directly by foreign companies, receiving in USD, EUR or even in bitcoins, abroad.

But what are the labor and employment risks/issues foreign companies should consider before engaging individuals in Brazil? Do they have to comply with local employment laws?

Firstly, it is important to have in mind that, according to Brazilian laws as well as case law, labor relationships (which include independent contractor relationships) and employment relationships with the provisions of services in Brazil are both subject to Brazilian labor and employment laws and, also, to the jurisdiction of Brazilian labor courts.

The parties cannot agree otherwise and, even if they do so by, for example, agreeing to an arbitration clause or to the application of US law, such contract would be deemed null and void. This is because, according to the Brazilian Federal Constitution, whenever there is a dispute involving the existence of a potential employment relationship between two contracting parties, Brazilian labor courts have jurisdiction to rule the dispute and such ruling must be made in accordance with Brazilian labor and employment laws.

In this context, it is important to have in mind that, although there is no statute prohibiting foreign companies from hiring Brazilian citizens, it is not possible, from a practical perspective, for a foreign company to engage an individual, in Brazil, under an employment relationship, without having a local subsidiary incorporated in Brazil. This is because there are certain obligations that employers must comply with vis-à-vis the Brazilian Government that require the existence of a Brazilian entity.

Due to this, foreign companies hiring individuals in Brazil usually engage them as independent contractors only, without an employment relationship.

In Brazil, independent contractors may be engaged (a) as individual independent contractors or (b) through legal entities incorporated by them (so called “PJs”).

Independent contractors are not entitled to labor and employment benefits (annual vacations and vacation bonus, Christmas Bonus, deposits into the Guarantee Fund for Length of Service (FGTS), benefits established by the applicable collective bargaining agreement, etc.), but solely the remuneration package agreed upon between the parties.

Payments made to independent contractors by foreign companies are also not subject to social security charges in Brazil, as the paying source is not a Brazilian entity.

This is why foreign companies are able to offer remuneration packages much more attractive to Brazilian individuals when compares to Brazilian companies. Not only they usually pay abroad, in USD or EUR, but also they do not collect charges in Brazil.

However, Brazilian laws do not avoid the pronouncement of a direct employment between independent contractors and the contracting company in the event the legal requirements for an employment relationship are found to have been met.

On the contrary: if the independent contractor renders services (i) on a personal basis, (ii) on a regular basis, and (iii) under the subordination/direction of the contracting company’s employees/representatives abroad, an employment relationship must be declared directly between the individual rendering services and the contracting company.

This is based on the general principle of “substance over form”, according to which an employment relationship shall exist directly between the contracting parties, regardless of any agreement entered into between them if all the legal requirements for an employment relationship described above are found to have been met in the case.

In this case, if the independent contractor files a labor lawsuit against the contracting company, it may be required to pay all labor and employment benefits described above, in accordance with Brazilian law. This risk exists regardless of the nature of the contract.

It is true that if the foreign entity does not have a Brazilian legal entity, the chances of materialization of the risks are lower, but they still exist. As there is no Brazilian entity, the independent contractors would have to sue the foreign company, which is time consuming and depends on how long the courts take to rule the case, etc. Even though the risk exists, it would be more difficult to enforce a decision against a foreign company.

The risks increase, however, if the foreign entity decides to incorporate a local entity in Brazil, as it will become liable for all potential past labor and employment liabilities. This is especially relevant for foreign companies plaining to set foot in the Brazilian territory.

Bearing this in mind, foreign companies should map potential risks and address them before engaging individuals in Brazil.

[1] https://s29814.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/MBO-Digital-Nomad-Report-2020-Revised.pdf, accessed on August 30, 2022.

[2] https://vocesa.abril.com.br/sociedade/o-futuro-do-anywhere-office/, accessed on August 30, 2022.

- Category: Real estate

On October 17, the Judicial Review Board of the State of Rio de Janeiro issued CGJ Ordinance 77/22 with the intention of facilitating the disposal of assets of estates before completion of probate, without the need for intervention by the Judiciary.

Under the new rule, it will be possible to sell an estate's assets by public deed, regardless of court authorization. The deed, however, must include and prove the payment, as part of the price, of the full causa mortis transfer tax on the entire inheritance, in addition to prior deposit of the fees due for the extrajudicial probate. In other words, instead of giving this part of the price to the seller, the purchaser will directly discharge these expenses of the estate.

The change aims to facilitate the sale of real estate during out-of-court probate, whether due to urgency on the part of the parties or the heirs' lack of resources to complete the probate process. It is not uncommon for the cost of fees and taxes to prevent the division of the estate or to resort to the courts in the probate process in an attempt to obtain a court order to authorize the sale of part of the estate and thus raise funds to pay for these expenses. The new rule, therefore, can be seen as an important litigation prevention measure.

It is fundamental to note, however, that failure to draw up the public deed of extra-judicial probate within 90 days from the acknowledgement of the prior deposit, unless there is a fully justified reason, will cause the seller to lose the fees deposited by the purchaser in favor of the notary public, since, in this case, the notarial act will be considered effectively performed.

Although the real estate transaction itself is not affected, it is recommended, therefore, that the parties assess the inclusion of a regulation on this subject in the deed of sale and purchase, with possible consequences and penalties if the established deadline is not met, in order to provide greater security for the parties and the transaction.

The property sold will be listed in the estate list for the purposes of determining the emoluments, tax classification, and calculation of the apportionment, but it will not be subject to partition. Its sale will be noted in the probate deed.

This new rule does not apply to disposal of real estate located outside the State of Rio de Janeiro and will also not control in cases where probate cannot be done up by a public deed in an extrajudicial manner and/or where there is an unavailability of assets in relation to one of the heirs or the executor.

The new regulation is an incentive for heirs to proceed with the extrajudicial division of property. At the same time, the rule relieves the Judiciary by stimulating the payment of transmission causa mortis, speeding up the process and benefiting the purchaser, who gains legal security with the regulation of the transaction.

- Category: Litigation

The Fourth Panel of the Superior Court of Appeals (STJ) completed in August the judgment of Special Appeal (REsp) 1.837.386/SP, in which it was litigated whether the promulgation of Precedent 326 of the STJ[1], based on the Code of Civil Procedure of 1973 (CPC/73), would conflict with the wording of article 292, V, of the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) in force.[2]

Among the provisions submitted for analysis by the court in the REsp,[3] article 86 of the CPC merits attention, according to which the parties must bear, proportionally, the case costs and the attorneys' fees in the event of reciprocal loss of suit.

According to the recent understanding of the STJ, established on the occasion of the judgment of REsp 1.837.386/SP, in actions for compensation for non-economic damages, even if the amount of the compensation awarded by the judgment is miniscule if compared to the amount indicated in the complaint, "there is no question of loss of suit for the plaintiffs, who were victorious in their claim for compensation," which reinforces the content set forth in Precedent 326.

This is because the plaintiff would be allowed to formulate a claim for compensation for non-economic damages in an estimated manner, such as, for example, using "generic formulas like 'compensation not less than', without an award in an amount higher than his estimate qualifying as an ultrapetita decision."

The discussion submitted to the STJ is old and subject to divergence. On one side, there are those who, in the legal scholarship[4] and in the case law,[5] defend maintenance of the validity of what is stated in the precedent. Considering that the judge, in theory, is be bound to the amount requested in the complaint to fix the quantum of the compensation, the understanding would prevail that, if the request for compensation for non-economic damages is granted, even if in an amount lower than that requested, there would be no partial or reciprocal loss of suit between the parties.

In this sense, although article 292, V, of the CPC expressly requires that a claim for non-economic damages be quantified and determined by the plaintiff when the suit is filed, the total loss of suit would fall to the defendant, since the amount indicated in the complaint for the award of compensation for non-economic damages would be merely an estimate.

From the point of view of constitutional law, the first current seeks to protect full access to Justice (article 5, XXXV, of the Federal Constitution), as it finds that the risk of the party incurring costs for loss of suit, in the case of partial acceptance of the claim for compensation, may inhibit the filing of suits seeking compensation for non-economic damages. In practice, this happens not infrequently, since the amount of compensation is derived from the subjective assessment of the judge.

In line with the understanding held by the STJ when ruling on REsp 1.837.386/SP, it would be inconsistent to impose a burden for loss of suit on plaintiffs who won a suit for compensation for non-economic damages, since, depending on the situation, the amount of the compensation set by the court could even be lower than the attorneys' fees imposed on the winner in the claim.[8]

Thus, by upholding the understanding set forth in Precedent 326, the STJ demonstrates its concern for the potential legal effects and consequences that would result from a possible overruling of said precedent, as provided for in article 21 of the Law of Introduction to the Norms of Brazilian Law (LINDB).[9]

On the other hand, as to the second trend, it is impossible to ignore that the CPC is explicit in requiring the plaintiff to present a certain and determined claim in “actions for compensation, including those based on non-economic damages", not allowing generic or estimated requests. Although we recognize the existence of legal authorization in article 324, paragraph 1, II, of the CPC for the formulation of a generic claim, "when it is not possible to immediately ascertain the consequences of the act or fact", this scenario does not apply to claims for non-economic damages.

This is because, even though the instability of the case law is undeniable, the courts, especially with the advent of the internet, have ample access to countless parameters to quantify claims for compensation according to the concrete case, as seen in case research in the courts of all the states in the federation, preparation of legal studies, among others.

Even if the judgment does not establish the exact amount of damages requested in the complaint, the judge should evaluate whether, in the concrete case, the plaintiff lost in a minimum part of the claim that would justify an exclusive judgment against the defendant for the costs for loss of suit, as provided for in the sole paragraph of article 86 of the CPC.

This interpretation honors the system provided for in article 7 of the CPC, assuring the parties exercise of the adversarial process, inasmuch as, in addition to allowing the defendant to discuss the extent of the amount sought by the plaintiff, it prevents irresponsible claims for compensation for non-economic damages due to the possibility of partial loss of suit.

Except in the case provided for in the sole paragraph of article 86 of the CPC, it seems reasonable that the percentage of the fees for loss of suit to be awarded in favor of the defendant's lawyer should observe the economic benefit obtained, reached by the difference between the excessive amount claimed and the amount awarded in the judgment as non-economic damages.

This understanding was ratified by Ruling 14/15 of the National School for Training and Improvement of Judges (Enfam),[10] approved by about 500 judges during the seminar The Judiciary and the new CPC, held from August 26 to 28, 2015, at the seat of the STJ itself.

In summary, we start from the premise that bringing suit in court involves risks, among them the burden of loss of suit. In this context, the procedural subjects, including the judge, have the duty to cooperate with each other to enable delivery of judicial relief (article 6 of the CPC).

On the one hand, it is incumbent on the plaintiff to prudently set the amount claimed for non-economic damages, under penalty of, failing to do so, bearing part of the burden for loss of suit. On the other hand, it is the judge's role, weighing the defendant's allegations to the contrary, to examine the reasonableness of the amount of compensation sought, taking into account the factual situation and the existing case law on the subject.

This is the co-participative and collaborative model of proceedings,[11] founded on the principles of legal security and due process of law provided for in article 5, XXXVI and LIV, of the Federal Constitution, which also lends itself to improving the case law.

Regardless of sympathy for one view or the other, the fact is that the CPC does not provide an express solution for the controversy. Considering that article 292, V, of the CPC deals specifically with actions for compensation based on non-economic damages, the best way to settle the issue might be to seek the adaptation of the procedural law through the ordinary pathway of the constitutional legislative process, through the popular participation of all interested parties.

Until this occurs, or the matter is submitted for judgment under the system of repetitive appeals provided for in articles 1036 et seq. of the CPC, the result of the judgment in the STJ will continue to be the target of reasoned criticism, especially in light of the robust case law and scholarly divergence on the subject.

[1] "In the action compensation of non-economic damages, the judgment at a lower amount than that requested in the complaint does not imply reciprocal loss of suit" (Special Court, decided on June 7, 2006).

[2] Article 292. The value of the cause shall be established in the complaint or counterclaim and shall be: (...) V - in actions for compensation, including those based on non-economic damages, the sum sought;

[3] In the appeal briefs, the appellant indicates violation of articles 186 and 927 of the Civil Code (CC) and of articles 85, paragraph 2, and 86 of the CPC.

[4] “An interesting position has been adopted by the case law regarding the action for compensation for non-economic damage. As the award of the amount of the compensation is of the judge's exclusive competence, the understanding of the Superior Court of Appeals has been fixed to the effect that, 'in actions compensation of non-economic damages, the judgment at a lower amount than that requested in the complaint does not imply reciprocal loss of suit’ (Precedent 326/STJ)." (THEODORO JÚNIOR, Humberto. Course on Civil Procedure Law. 56th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Forense, 2015, p. 308).

[5] STJ, REsp 579.195-SP, opinion drafted by Justice Castro Filho, 3rd Panel, decided on October 21, 2003; TJMG, Motion for Clarification-Cv 1.0000.22.037448-2/002, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge José Augusto Lourenço dos Santos, 12th Civil Chamber, decided on September 2, 2022; TJSP, Civil Motion for Clarification 1000476-56.2017.8.26.0412, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge Coelho Mendes, 10th Chamber of Private Law, decided on February 5, 2019.

[6] "A problem that deserves careful analysis is that of a generic claim in actions for non-economic damages: should the plaintiff quantify the amount of the compensation in the complaint or not? The answer is in the affirmative: the claim in these lawsuits must be certain and determined, limiting the plaintiff in how much he seeks to receive as compensation for the non-economic damage he has suffered. Who, other than the plaintiff himself, could quantify the 'non-economic pain' he claims to have suffered? How could a stranger, and therefore unaware of this 'pain', assess its existence, measure its extent, and quantify it in money? The judge's job is to judge whether or not the amount requested by the plaintiff is due; it is not incumbent on him, without a provocation from the plaintiff, to say how much the amount should be. Furthermore, if the plaintiff requests that the judge determine the amount of the compensation, he will not be able to appeal decisions that, absurdly, set it at one Brazilian Real (R$ 1.00), since the claim would have been fully granted, with there being no way to find an interest on appeal. Article 292, V, of the CPC seems to go in this direction, by imposing as the amount in controversy the amount of the prayer for relief in actions for compensation, 'including those based on non-economic damage'. The illiquidity of the claim is only possible, in these cases, if the act that caused the damage may also have repercussions in the future, generating other damages (e.g.: a situation in which the non-economic damage is continuous, such as undue registration in personal credit history or continuous offense to one's image); then, one would apply subsection II of paragraph 1 of article 624, commented here. Outside this case, the formulation of an illiquid claim is unacceptable" (DIDIER JÚNIOR, Fredie. Curso de direito processual civil: introdução ao direito processual civil, parte geral e processo de conhecimento [“Course on civil procedural law: introduction to civil procedural law, general part and cognizance process”], 17th revised ed., expanded and current. Salvador : JusPodivm, 2015, p. 581).;

[7] TJRJ, Appeal 0002064-42.2017.8.19.0079, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge Alexandre Câmara, 2nd Civil Chamber, decided on September 16, 2020.

TJSP, Appeal 1002707-40.2016.8.26.0655, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge Antonio Rigolin, 31st Chamber of Private Law, decided on January 23, 2018. TJ-MG, Appeal 10000191312040001, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge Lílian Maciel, decided on January 20, 2020. TJ-DF, 0723140-23.2018.8.07.0001, opinion drafted by Appellate Judge Leila Arlanch, 7th Civil Panel, decided on July 24, 2019.

[8] STJ, AgRg no Ag 459.509-RS, opinion drafted by Luiz Fux, 1st Panel, decided on November 25, 2003

[9] Article 21. The decision that, in the administrative, oversight, or judicial spheres, orders the invalidation of an act, contract, adjustment, process, or administrative rule must expressly indicate its legal and administrative consequences.

[10] Enfam Ruling 14/2015: "In the event of reciprocal loss of suit, the difference between what was claimed by the plaintiff and what was granted, including with regard to awards of non-economic damages, shall be considered the defendant's economic benefit, for purposes of article 85, paragraph 2, of the CPC/2015" (emphasis added)

[11]DIDIER JR, Fredie "The three models of procedural law: inquisitive, dispositive, and cooperative." Revista de Processo: RePro, v. 36, n. 198, p. 213-225, Aug. 2011.

- Category: Capital markets

The Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil (CVM) published CVM Guidance Opinion 40, approved by its joint committee, on October 11th. The document makes public the regulator's consolidated understanding of the rules applicable to cryptoasset securities. The aim of the agency is to guide market participants and bring legal security and predictability to development of the sector.

Cryptoassets, or virtual assets, are divided into cryptocurrencies, such as bitcoin, altcoins, and stablecoins, and tokens, such as utility tokens, security or equity tokens, and non-fungible tokens (NFT).

CVM's position is that bitcoins and most other cryptocurrencies are outside its regulatory scope, as they are not considered securities or financial assets.[1] The competence of the agency, therefore, does not cover service providers that perform administration, management, custody, or operate exchanges on which only cryptocurrencies are traded.

Tokens, in turn, may fall under the regulatory reach of the CVM, provided they are classified as securities. When this occurs, all service providers involved in the issuance, public distribution, centralized deposit, clearing and settlement, bookkeeping, and issuance of certificates, custody, as well as brokers that act, directly or indirectly, in the secondary trading of these tokens must comply with CVM regulations applicable to the respective professional activities performed.

Currently underway in the National Congress, Bill 4,401/21,[2] known as the Legal Framework for Cryptocurrencies, proposes regulation of virtual asset service providers. Its main regulatory focus, however, is virtual assets used for investment or payment that are not considered securities, since there is no regulation of their activities or supervision by a regulatory body.

The bill expressly excludes regulation of virtual assets considered securities, which are already subject to Law 6,385/76 (Capital Markets Law) and to the CVM’s supervision.

There is, therefore, complementarity between the initiatives of the CVM and the Legislative Branch regarding the regulation of the cryptoasset sector (virtual assets) as a whole. The Legal Framework for Cryptocurrencies bill even makes it clear that the CVM's jurisdiction over tokens considered securities should remain unchanged.

Regarding CVM Guidance Opinion 40, we highlight the main guidelines:

- Technological neutrality: following the international trend, the CVM adopts a neutral posture in relation to the technologies employed and is receptive to new technologies. The technologies behind cryptoassets (e.g. blockchain or other DLT) are not subject to regulation in the capital markets, nor are they relevant to the process of classifying an asset as a security or for submitting a certain activity to CVM regulation.

- Cryptoasset categories: the CVM chose to adopt a functional approach in categorizing cryptoasset to indicate their legal treatment, classifying them among:

- Payment tokens: their functionality replicates that of currencies, as a unit of account, medium of exchange, and store of value.

- Utility token: their functionality is to purchase or access a certain product or service.

- Asset referenced token: their functionality is to represent one or more assets, which can be tangible or intangible, such as, for example, security tokens, stablecoins, non-fungible tokens (NFT), and other assets subject to tokenization operations.

A single cryptoasset may fall into more than one category according to the functions performed and the associated rights. Furthermore, tokens may or may not be characterized as securities, depending on the analysis of each case, based on the guidelines explained below.

- Classification of cryptoassets as securities: the classification of cryptoassets as securities is important as this brings about the CVM's jurisdiction over issuers and public offerings of these virtual assets, as well as the agents involved in the brokerage, bookkeeping, custody, centralized deposit, registration, clearing, and settlement of transactions involving cryptoassets considered securities, in addition to the administration of organized markets for secondary trading of this type of cryptoasset.

According to the CVM’s guidance, cryptoasset securities should be considered securities in the following cases:

- If the token is characterized as a publicly offered collective investment contract that generates holding, partnership, or remuneration rights, including those resulting from the provision of services, whose income arises from the efforts of the entrepreneur or third parties, as set forth in subsection IX of article 2 of the Capital Markets Law.

This can occur even if the collective investment vehicle invests in or takes on exposure to cryptoassets that are not considered securities, such as bitcoin or other cryptocurrencies. According to the administrative case law of the CVM, the characterization referred to in the above paragraph does not depend on a prior opinion of the CVM but on the application of the Howey Test, which will be explained below.

- If the token is the digital representation of any of the securities provided for in subsections I to VIII of article 2 of the Capital Markets Law, that is:

- shares, debentures, or subscription warrants;

- coupons, rights, subscription receipts, and certificates of splitting of such receipts;

- certificates of deposit of securities;

- debenture notes;

- quotas of securities investment funds or investment clubs in any assets;

- commercial notes;

- futures, options, and other derivatives contracts, whose underlying assets are securities; and

- other derivative contracts, regardless of whether or not the underlying assets are cryptoassets.

- If the token is the digital representation of certificates of receivables offered publicly or admitted for trading on a regulated securities market, as provided for in article 20, paragraph 1 of Law 14,430/22 (Legal Framework of Securitization Companies).

- Collective investment contracts and the Howey Test to characterize a publicly offered cryptoasset as a collective investment contract under the terms of subsection IX of article in order to classify a security as a marketable security, the CVM uses the Howey Test, inspired by the method used by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC).

The CVM lists the characteristics that must be taken into consideration for classification purposes when analyzing a case:

- investment;

- formalization;

- collective nature of the investment;

- expectation of economic benefit by entitlement to some form of holding, partnership, or remuneration, which must result from the efforts of the entrepreneur or a third party, and not from external factors, such as, for example, equity participation or redemption rights, remuneration agreements, and receipt of dividends;

- entrepreneurial or third-party effort, such as when the entrepreneur's or the third party's actions are necessary for the creation, improvement, operation, or promotion of the enterprise; and

- public offering.

- Public Offering: the public distribution of cryptoassets considered securities in the capital markets is subject to prior registration with the CVM, as provided for in article 19 of the Capital Markets Law, except in situations in which the distribution is expressly exempted under the terms of the infra-regulatory rules issued by the CVM, as delegated to the agency by articles 8, I, and 19, paragraph 5, of that law.

At the infra-legal level, issues and offers for public distribution of securities are currently regulated by the CVM in CVM Instruction 400/03 and in Instruction 476/09. These two instructions, however, will be replaced and repealed on January 2, 2023, with the entry into force of CVM Resolution 160/22, which will inaugurate a new regulatory framework for public offerings of securities.

In addition, as the public offering of cryptoasset products is common through the internet and without geographic restrictions, the CVM advises that, in this case, one must observe the parameters of CVM Guidance Opinion 32 and CVM Guidance Opinion 33, both of 2005 and applicable to public offerings of securities issued abroad for a target public residing, domiciled, or incorporated in Brazil.

In the new opinion, the CVM supplemented the guidelines given in 2005 with information regarding the criteria to be taken into consideration in the evaluation of the:

- effectiveness of measures to prevent the general public from accessing the page containing a private offering of securities; and

- irregularity of public offerings of securities abroad, without the due registration with the CVM, and of brokerage of transactions with securities issued abroad, including derivatives, intended, in both cases, to the general public resident in Brazil.

- Informational framework and valuing of of transparency: based on the principle of wide and adequate disclosure that guides the information framework adopted by the CVM, the agency has guided the participants of the cryptoasset market classified as securities to value maximum transparency in their issuance, public distribution, and trading in the secondary market.

It recommended that the applicable regulation on this subject be observed and pointed out as an example CVM Resolution 80/22, CVM Resolution 86/22, and CVM Resolution 88/22, as applicable in view of the characteristics of the cryptoassets and the issuer, under the terms of articles 19 and 21 of the Capital Markets Law. As explained above, the current regulations applicable to public offerings of securities must also be complied with.

Regarding the admission for trading in the secondary market, the agency guided that cryptoassets classified as securities must be traded in organized markets that have authorization from the CVM, pursuant to CVM Resolution 135/22.

In a complementary way, it highlighted as an example a minimum set of information related to the rights of crypto holders and to trading, infrastructure, and ownership of cryptoassets, the provision of which in language accessible to the target audience of the offering was considered important by the agency.

The regulator has indicated that it may evaluate the creation of a more flexible framework in the future depending on the evolution and development of the issue. For now, it recommended that market participants give preference to broad transparency and observe all the rules that guide the disclosure of information in effect regarding their respective activities, so that the investor can make a more informed investment decision.

- Role of brokers: the CVM highlighted the role of brokers that act, directly or indirectly, in the secondary market for trading of cryptoassets considered securities. In addition to the duty to observe applicable regulations, the agency again emphasized the importance of disclosing information to investors.

It recommended that, within their area of expertise, these participants act to ensure an adequate level of transparency and information regarding the characteristics and risks associated with virtual assets in trading, especially when cryptoassets are offered directly, rather than through a regulated product such as, for example, investment funds and ETFs - these investment vehicles are already required to comply with a fairly comprehensive information arrangement.