Publications

- Category: Tax

Beginning the series of articles on the changes implemented by Executive Order No. 905, published on Tuesday, November 12, we review below changes in the rules for creating and paying a Profit Sharing Plan (PLR).

Granted by companies to their employees as a means of integrating capital and labor and as an incentive for productivity gains, PLRs are not included in the calculation basis of social security contributions, provided that the legal requirements are duly fulfilled. Currently, Law No. 10,101/2000 regulates the matter and expressly provides for, in its articles 2 and 3, the requirements for the implementation of PLR plans.

Despite the existence of clear regulations on the subject, companies are often surprised by assessments based on requirements that are not found in the law.

The Superior Chamber of Tax Appeals (CSRF), often based on the casting vote, has ratified some of the theories and requirements created by the tax authorities, thus assuming the position of a veritable legislator, which seems to go beyond its jurisdictional function.

In this scenario, MP 905 comes to the aid of taxpayers in order to combat and eradicate illegalities perpetrated by the CSRF. In general, the various changes promoted by MP 905 seek to clarify the text of the rules used as a basis for constructing restrictive interpretations of the legislation by the tax authorities and administrative courts.

The table below compares, briefly, the position that was being consolidated before the CSRF with the new rules introduced by MP 905:

|

Legal requirement |

CSRF majority position |

Rules established by MP 905 |

|

Participation by the labor union |

||

|

Implementation of PLRs through collective bargaining agreement or joint committee chosen by the parties, also including a representative appointed by the labor union. |

The absence of labor union participation from the same territorial base, even in the event of refusal on the part of the union, entails disqualification of PLR payments. |

Implementation of PLRs through collective bargaining agreement or joint committee chosen by the parties. Labor union participation is waived if the PLR is implemented by a committee elected by the parties. |

|

Definition of rules |

||

|

PLR plan should contain clear and objective rules. |

Disqualification of PLR payments where, based on a subjective interpretation, the board considered the targets not clear or objective. |

In establishing substantive rights and ancillary rules, including the setting of amounts and the exclusive use of individual goals, the autonomy of the will of the parties to the contract must respected and prevail vis-à-vis the interest of third parties. |

|

Prior negotiation of rules |

||

|

The PLR plan may be based on previously agreed-upon schedules of goals, results, and deadlines. |

The PLR plan must be signed before the start of the period for measuring targets (i.e., before the start of the calendar year, if it is an annual plan). |

The rules set in a signed instrument are considered previously established: (i) prior to advance payments, when provided for; and (ii) at least 90 days in advance of the date of payment of the lump sum or final installment, if there is advance payment. |

|

Frequency of payment |

||

|

It is prohibited to pay any advance or distribution of funds as profit sharing of the company more than two (2) times in the same calendar year and at a frequency of less than one (1) calendar quarter. |

All PLR installments should be disregarded and not only those that exceeded the frequency. Social security levied on all amounts paid in the period. |

Noncompliance with the frequency of payments only disqualifies payments made in violation of the rule, thus understood to be the following: (i) payments in excess of the second, made to the same employee, within the same calendar year; and (ii) payments made to the same employee at a frequency of less than one calendar quarter from the previous payment. |

Despite the good news for taxpayers, the provisions related to the payment of PLR, according to MP 905, will only have effects when an act of the Minister of Economy attests to compatibility with the tax results targets provided for in the schedule of the Budgetary Guidelines Law itself and compliance with the provisions of Supplementary Law No. 101/2000 and the provisions of the Budgetary Guidelines Law related to the matter.

Still, MP 905 indicates that the interpretations that were being adopted by CSRF were not in line with the spirit of the law, which may be used as an additional argument by taxpayers in pending administrative and judicial proceedings.

We will continue to monitor the evolution of the subject and its potential developments.

- Category: Tax

Continuing the series of articles on the changes implemented by Executive Order No. 905, published last Tuesday, we review below the changes regarding the payment of premiums by companies to their employees.

As already discussed in this article, the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service, upon publishing Cosit Response to Public Inquiry No. 151/2019, created difficulties for companies in paying premiums and went against the provisions of article 28, paragraph 9, "z", of Law No. 8,212/1991, which expressly excludes premiums from salary for the purposes of contributions. Instead of clarifying the issue and establishing guidelines on the use of premiums, the body maintained the confusion and lack of legal certainty, because, although it does not have the force of law, Cosit’s resolution of public inquiry binds the Public Administration and guides the actions of tax inspectors.

In summary, according to the restrictions imposed by Cosit Response to Public Inquiry No. 151/2019, only payments made spontaneously and unexpectedly that (i) were not due to contractual agreements (contracts, policies, job postings, etc.) could be considered premiums and (ii) derive from performance above what is ordinarily expected, objectively proven by the employer.

Aiming to restore legal certainty on the subject and remove the obstacles created by the Federal Revenue Service, MP 905 established the validity of the premiums dealt with in paragraphs 2 and 4 of article 457 of the Consolidated Labor Laws (CLT) and item “z”, paragraph 9, of article 28 of Law No. 8,212/1991, regardless of the respective form of payment and means used to fix it. Even unilateral acts of the employer, agreements between the employer and the employee or group of employees, and collective bargaining rules, including when premiums are paid by foundations and associations, are valid, provided that:

the payment is made exclusively to employees, individually or collectively;

the payment of any advance or distribution of funds is limited to four times in the same calendar year and once in the same calendar quarter;

the premiums result from performance higher than what is ordinarily expected, evaluated at the discretion of the employer, provided that ordinary performance has been previously defined; and

the rules for the premium are established prior to the payment.

From an analysis of MP 905, it is evident that the intent of the changes is to make it clear that the parties may fix the terms and conditions for payment of premiums through a written document, via a bilateral act (contract, agreement, or collective bargaining agreement) or unilateral act (internal or communicated policy).

The rules regarding payment of premiums must be filed by any means for a period of six years from the date of payment.

In our view, this point resolves the controversy over the requirement of "liberality." Based on MP 905, the understanding that we defended in a prior article prevails, to the effect that liberality is all that is granted by the company beyond what is required by law. Therefore, premiums cover any and all forms of variable remuneration, even if contractually agreed upon, provided that the other requirements set forth in article 457 of the CLT are observed.

Another important issue addressed by MP 905 is the requirement of “payment due to performance higher than that which is ordinarily expected.” According to the changes implemented, this assessment may be done at the discretion of the employer, provided that the ordinary performance has been previously defined by it, unilaterally or by agreement.

MP 905, however, brought in restrictions on frequency of the payment, which directly impacts on companies that have been making monthly premium payments.

We will continue to monitor the evolution of the subject and its potential developments.

- Category: Capital markets

It is increasingly important for publicly traded companies to dedicate themselves to fully complying with the obligations imposed by current laws and regulations, keeping themselves up to date, and having an adequate Investor Relations Department and legal support structure. Important changes have been observed in sanctions rules, as well as a significant increase in the obligations to be fulfilled, which increases the risks of non-compliance. We emphasize the sanction actions of the Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission (CVM) for companies listed as public companies and the regulations of B3 S.A. - Bolsa, Brasil, Balcão (B3) for companies listed in the B3.

Recent changes in the rules for CVM sanctions procedures include profound changes by Law No. 13,506/17 (which followed Executive Order No. 784/17, which expired without being converted into law). The topic was dealt with in this portal in two articles:

- An analysis of the “new” administrative sanctions procedures of Bacen and CVM

- Law No. 13,506 and the actions of the Central Bank and CVM

In 2019, due to these legislative changes, CVM sought to consolidate the normative acts that regulated its sanctions procedures by publishing CVM instructions 607, 608, and 609, already dealt with in the Legal Intelligence Portal:

- CVM publishes new framework to regulate its sanction actions

- What changes in practice with the new regulatory framework for CVM's sanction actions

Regarding corporate governance, there have also been recent changes to applicable rules and regulations, among which one may highlight:

- Amendments to the provisions of the “novo mercado” regulation;

- Mandatory distance voting and its recurring updates; and

- The requirement to publish corporate governance reports.

- After so many changes, how are CVM's sanctions activities and B3's regulatory actions having an impact on companies?

In an analysis of the report on CVM’s sanctions activities, the 140% increase in the number of sanctions imposed by the authority in the year 2018, compared to 2017, is striking. Of particular note is the substantial increase in the number of warnings (342%) and fines (133%). In 2019 (until June 30), 106 sanctions were applied (72 of them in the form of fines), a number similar to the total recorded in 2017 (128 sanctions).

Another noteworthy fact is the increase in the average amount of the fines imposed by the authority (as a result of the increase allowed by Law No. 13,506): while in 2017 and 2018 the average amounts of the fines imposed by CVM was, respectively, R$ 1.5 million and R$ 1.4 million, in the first six months of 2019 it reached R$ 10.7 million.

Thus, the total amount of the fines imposed by CVM in the first half of this year already exceeds R$ 770 million, more than double what was collected via fines in 2018 and almost four times more than in 2017.

There was also a strong increase in the number of consent decrees approved by CVM joint board. In 2018, the increase was 56% over 2017, totaling 179 consent decrees. In addition, the amounts involved also increased, which we believe to be a reflection of the increase in the fines provided for in Law No. 13,506: in 2017, the total was R$ 20.7 million, with an average amount of R$ 180 thousand per consent decree; In 2018, it was R$ 41.2 million, with an average of R$ 230 thousand per consent decree; and, in 2019, only in the first half of the year, the total was R$ 25.1 million (considering the 73 consent decrees approved up to June), with an average unit value of R$ 344 thousand.

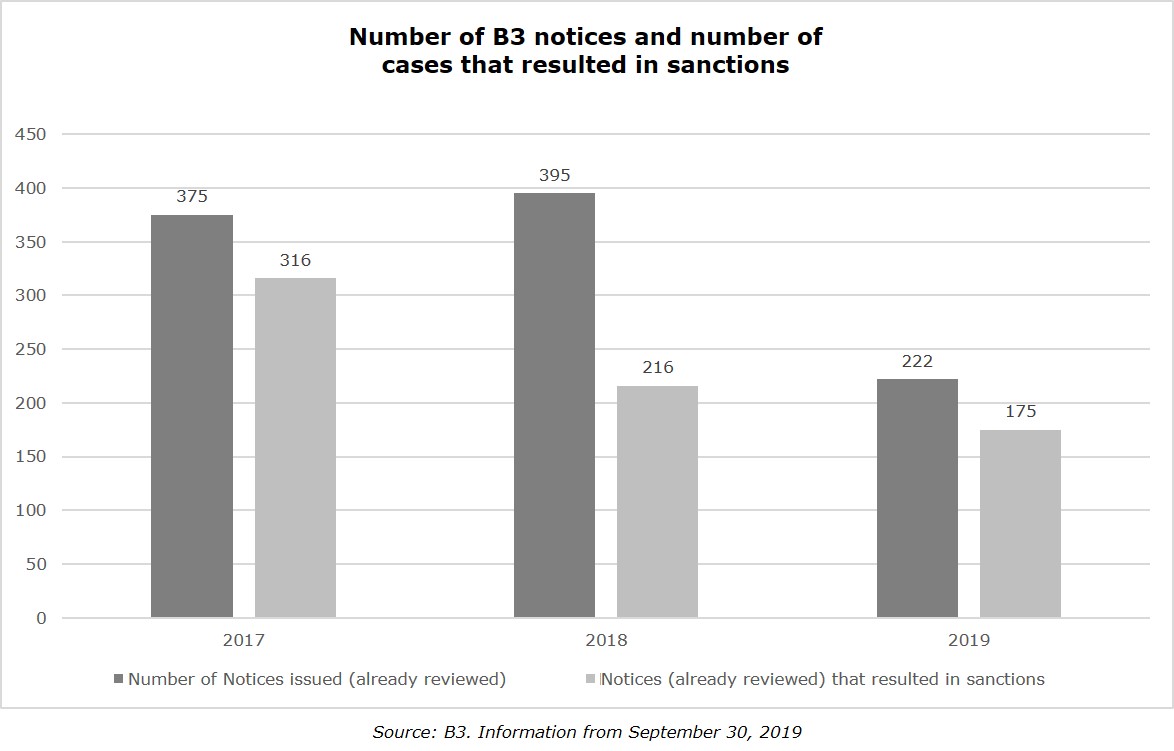

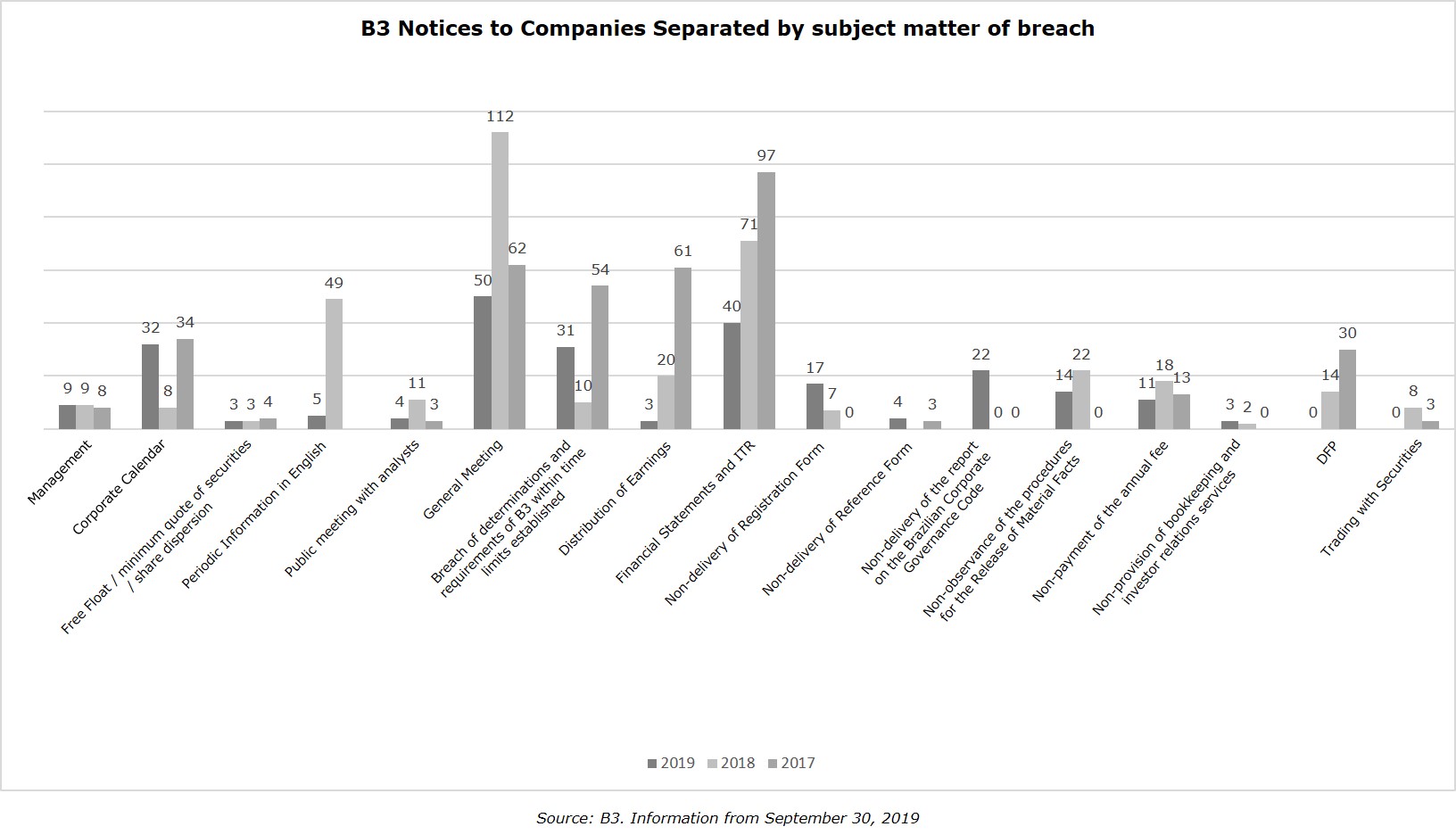

Regarding the regulatory action of B3, we review the enforcement report available on the Internet, which shows the number of notices sent by B3 to companies, and we find that there is not a significant variation from one year to another, as happened with CVM:

However, the variation in the most recurring matters related to notices sent by B3 in 2017, 2018, and in the first nine months of 2019 is significant.

The evolution in the numbers shows the importance that companies and managers must give to the full compliance with regulations for public companies in order to avoid heavy fines and other penalties. It is important to remember that the opening of investigations and proceedings also represents expense for and attention from management, which may divert its focus from executing the company's business strategy.

In addition, the increasing sanction actions of CVM and other self-regulatory entities, with concomitant increases in fines, may result in higher premiums in the purchasing of directors & officers (D&O) insurance and increased use of indemnity agreements by the companies in question, in substitution for insurance. In this sense, it is worth observing the dictates of CVM Guidance Opinion No. 38/2018, the subject of analysis by another article in this portal.

- Category: Labor and employment

In addition to instituting the Green and Yellow Employment Contract and implementing various significant changes in labor and social security laws and regulations and in the rules regarding payment of Profit Sharing, Executive Order (MP) No. 905, published last Tuesday, November 12, amended article 224 of the Consolidated Labor Laws (CLT) relating to the working hours of bank employees.

Before the publication of the executive order, the normal duration of working hours of employees at banks, banking houses, and Caixa Econômica Federal was six continuous hours on business days, with the exception of Saturdays, totaling 30 hours of work per week.

With the publication of MP 905, the normal working hours for bank employees became six hours per day exclusively for those who work as a teller, expressly excepting the possibility of agreeing on longer working hours, at any time, via individual written agreement or collective bargaining agreement. In relation to other bank employees, working hours will be eight hours per day.

In the previous wording, article 224 of the CLT expressly stated that the normal working hours of bank employees did not include Saturdays, since activities should be performed from Monday to Friday. However, the new wording made no provisos/exceptions regarding the subject. Accordingly, there is no longer a legal prohibition on having bank employees work on Saturdays, subject to the limit of the 30-hour workweek.

However, the discussion regarding bank employees' ability to work on Saturdays is not limited to the wording provided for in article 224 of the CLT. This is because, according to Precedent No. 113 of the Superior Labor Court (TST), which is still in force, the bank employees' Saturday is an unworked business day.

In this sense, the amendment by MP 905 of article 224 of the CLT should lead to the cancellation of TST Precedent No. 113, since it denotes an apparent incompatibility with the Court’s summarized understanding, especially if the MP is approved by the Brazilian Congress.

Another issue that may give rise to debate is whether the weekly working hours of bank employees, with the exception of tellers, are 40 or 44 hours per week, as there is no express provision on the subject in article 224 of the CLT, as is the case with 30-hour work week shift for tellers.

Considering the limitation of 30 hours per week for tellers, it could be interpreted logically that, for other employees with a daily shift work of eight hours, the work week would be 40 hours.

However, in addition to the fact that article 224, head paragraph, of the CLT does not exclude Saturday from bank employees’ working hours, TST Precedent No. 124 provides for the application of divider of 220 in calculating bank employees' overtime hours with eight hour work days. Using the divisor 220 for the 30 days of the month we get 7.33 hours per day, which, multiplied by 6 days a week, results in a 44-hour weekday, which is why the discussion on the bank employees' weekly working hours has not yet been overcome.

With regard to the express authorization for working hours over six hours per day for bank employees working as tellers, it is important to remember that this possibility was already being defended by the labor courts, based on the systematic interpretation of articles 59 and 225 of the CLT.

Article 225 of the CLT provides that bank employees may work overtime on an exceptional basis, and article 59 of the CLT provides that daily working hours may be increased with overtime, not exceeding two hours, pursuant to an individual agreement or collective bargaining agreement.

That is, the only way to preserve both provisions in the legal system would be to find that bank employees may work overtime (i) exceptionally, even if there is no agreement in this regard; and (ii) habitually, when the agreement is formalized in the course of the employment contract, since article 225 of the CLT itself states that the general principles regarding the duration of work should be observed, such as the possibility of formalizing extension of working hours provided for in article 59 of the CLT.

This interpretation has not yet settled by the labor courts, but has been reinforced by MP 905, as article 225 of the CLT remained unchanged, thus maintaining the provision regarding the exceptionality of extension of bank employees' working hours. In view of the limitation of the special working hours to bank employees working as tellers, it should be considered that the wording provided for in article 225 is also limited to these professionals.

In addition to the amendment of article 224, head paragraph, of the CLT, and the inclusion of paragraph 3 mandating an eight-hour workday for other bank employees, paragraph 4 was also included in article 224 of the CLT, establishing that, in the event of a judicial decision that rules out an employee's classification within the exception provided for in paragraph 2 of article 224, the amount due by virtue of overtime and consequential payments must be fully deducted or offset in the amount of the bonus for the position and consequential payments.

This change was possibly the least impactful for this group of employees, as it only reproduces the first paragraph of section 11 of the Bank Employees’ Collective Bargaining Agreement (CCT), which since 2018 has governed any possible offsetting between overtime hours and position bonuses, in the event of de-qualification, in a labor claim, of the position with the bank as being one of trust.

The provision set forth in the CCT is now applicable to labor claims filed as of December 1, 2018, and, therefore, has been known to this group of workers for at least one year. However, the reproduction of this provision in the CLT is important in settling its application, since the validity of section 11 of CCT 2018/2019 has not yet been consolidated by the labor courts. The reason for this is the fact that some judges demonstrated a certain resistance to applying it, arguing that the provision constitutes intervention into the role of the judge, which is exclusive to the Judiciary, and, therefore, is not a question of the prevalence of what is negotiated over what is legislated.

Some judges also contend that employees hired before the effective date of the provision may not undergo prejudicial changes in the conditions of the labor contract, under the terms of article 468 of the CLT.

The matter was apparently settled with the publication of MP 905, which is immediately effective in relation to article 224 of the CLT.

The term of duration of MP 905 is 60 days, extendable once for the same period. If not converted into law during this period, the text will lose its effectiveness. This means that although the changes in bank employees' working hours indicate a positive and expected change, especially given that the activity of this group of employees in modern society does not have the same peculiarity that supported its special framework, it is possible that the text suggested by MP 905 not be converted into law, as we observed in relation to MPs 808/17 and 873/19.

Accordingly, we recommend that prior to making any changes to employees' employment contracts, even if via contractual amendment, financial institutions should be properly advised by their legal department in order to avoid undue or inapplicable changes in view of the still provisional nature of the executive order.

We will cover the main changes of MP 905 in the next articles in this series. Click here to read the analyses already published.

- Category: Environmental

One of the most important changes brought about by Federal Law No. 13,874/19, known as the Economic Freedom Law and arising from the conversion into law of Executive Order No. 881/19, is the waiver of prior licensing for the exercise of economic activities defined as being “low risk." Subsection I of article 3 of the law provides for the possibility of waiving the presentation of prior licenses, authorizations, registrations, or permits for the regular operation of low-risk economic activities that may be performed by any individual or legal entity essential to Brazil’s development and economic growth.

In order to determine what constitutes a low-risk economic activity, the law, in its paragraph 1, provides that this classification must be the result of an act of the Federal Executive Branch, in the absence of specific state, federal district, or municipal legislation. It is worth remembering, on this point, that the competence for land planning and defining activities is, in general, assigned to municipalities.

In order to comply with the provision of law with a general and subsidiary standard, the Steering Committee of the National Network for the Simplification of Registration and Legalization of Companies and Business (CGSIM) published, on June 12, 2019, in the Federal Official Gazette, Resolution No. 51, which deals with the definition of low-risk economic activities in order to comply with MP 881/19.

The resolution conceptualizes low-risk (or “low-risk A”) economic activities as those that do not call for a site visit for their continuous and regular exercise, and classifies 287 activities into this concept. Comparatively, in the city of São Paulo, low-risk activities are classified in Decree No. 57,298/16 and conceptualized in Law No. 16,402/16. Under the new legislation, they must prevail for the purpose of dispensing with the documentation necessary for the regular performance of these activities.

As for the scope of the waiver of licensing, the law is clear in providing that “public acts of liberation of economic activity” are waived. Thus, in a restrictive interpretation, the waiver of licensing may conceptually encompass municipal business licenses, but should not, in theory, encompass Fire Inspection Reports and the Certificate of Completion of Works (Inhabit), since both refer to the good standing of the building and not just the activities to be performed there.

In this respect, although the law does not expressly provide for its application in environmental issues, there is also room to hold that, in relation to these “low impact” activities, there is also no need to submit to environmental licensing.

For situations that require release from the Federal Public Administration or even from states and municipalities that have voluntarily bound themselves to this procedure, subsection IX of article 3 provides that, after the presentation of all the necessary supporting elements for the procedure to release the economic activity, the applicant will be informed of the maximum period stipulated for the review of its application. In addition, once the deadline has elapsed without a response from the competent authority, silence will imply tacit approval for all purposes, except in cases expressly forbidden by law, such as the in the case of a financial commitment by the Public Administration or when the procedure relates to tax issues.

The base text sent for presidential signature provided a caveat to this provision regarding environmental licensing, providing that the specific deadline was not to be confused with those of Complementary Law No. 140/11, which regulates the competence for licensing and defines the deadlines for processing environmental licensing proceedings. However, this caveat was the subject of a presidential veto, on the grounds that the provision was unconstitutional because it violated the government's duty of environmental prevention.

Complementary Law No. 140/11 provides that expiration of the licensing deadlines, without the issuance of an environmental license, does not imply tacit issuance thereof, thus representing a prohibition expressed in law. Therefore, the provisions of Law No. 13,874/19 regarding deadlines for public acts of release, although it may raise doubts, will not apply to environmental licensing.

These changes should expedite the opening of low-impact establishments, generally related to office activities and the provision of technical services, such as engineering, architecture, advertising, and general administrative support. The changes should also affect administrative licensing procedures, as they provide that the licensing agency is bound to meet deadlines vis-à-vis the interested party. Under the law, however, the loosening of the system is not complete. The competent supervisory bodies will continue to be in charge of supervising and assessing establishments that are in disagreement with the law, either sua sponte or as a consequence of a complaint sent to the competent authority.

Another aspect of the Economic Freedom Law to be highlighted is article 3, subsection XI, which eliminates the requirement for abusive compensatory or mitigating measures against private parties in impact studies or other releases of economic activity under urban planning law. The requirement of execution or provision of any kind for areas or situations beyond those directly impacted by the economic activity, as well as unreasonable or disproportionate measures, are classified as abusive, as are those that were already planned before the requirement of the private party, except in cases of impact from the activities in this planned measure.

- Category: Environmental

In an extra edition of the Official Federal Gazette of September 20, Law No. 13,874/19 was published, establishing the Declaration of Rights of Economic Freedom, arising from Executive Order No. 881. Although the law does not explicitly mention its application in environmental law, we must understand that this is a transdisciplinary branch and permeates the discussion of various other areas. For this reason, the Economic Freedom Law will also be applied in environmental issues.

Its changes in this area address, in short, authorizations in general and the licensing process. First of all, the law provides for the right of every person, whether an individual or legal entity, to carry out low-risk economic activity without the need for any public acts in order to authorize the economic activity, including environmental licensing and any other authorization on the part of the Public Administration. When not provided for by law, the classification of such activities will be done by an act of the federal Executive Branch. As a result, there will be less involvement of environmental agencies and their staff in determining which activities will be exempt from licensing, which may be questioned before the Judiciary.

Another point is that the supervision of the exercise of these activities will be carried out later, which may be considered contrary to the principle of prevention. On the other hand, this measure reduces discretion and varying interpretations. If the classification of activities is drafted well, it will facilitate supervision by environmental agencies and planning and prevention by developers, increasing legal certainty.

For activities that are not low risk, it is worth mentioning the provision of an express deadline for the review of requests for public acts of authorization as an essential right for Brazil's development and economic growth, except for the legal prohibitions. Once the deadline has expired, if the competent authority does not rule on the request, it shall be deemed to have been tacitly approved for all purposes.

The base text sent for presidential signature provided a caveat to this provision, providing that the specific deadline was not to be confused with those of Complementary Law No. 140/11, which defines the deadlines for processing environmental licensing proceedings. However, this caveat was the subject of a presidential veto, on the grounds that the provision was unconstitutional because it violated the government's duty of environmental prevention.

Complementary Law No. 140/11 also expressly states that expiration of the licensing deadlines, without the issuance of an environmental license, does not imply tacit issuance thereof, thus representing a prohibition expressed in law. Therefore, we believe that the provisions of Law No. 13,874/19 regarding deadlines for public acts of authorization, although it may raise doubts, do not apply to environmental licensing.

This subject has already been widely discussed in various bills and should be the subject of one of the next major environmental debates in Congress with Bill No. 3,729/04 (General Law on Environmental Licensing). Tacit approval of environmental licenses is repeatedly criticized due to the understanding that environmental licensing is a preventive tool and loses its meaning and essence, and therefore its function, if used as an a posteriori instrument, as it may be impossible to reverse any environmental damage.

The same reasoning does not apply, however, to other environmental authorization, such as clearance of vegetation or authorizations issued by auxiliary bodies such as Iphan, Funai, ICMBio, and Fundação Cultural Palmares, which may be tacitly approved under the new legislation. Although in its reasons for veto, the Brazilian President’s Office justified the unconstitutionality of tacit approval also based on the impossibility of regulating only one type of environmental license, implying that the other authorizations should also respect the duty of prevention, this was not reduced to positive law in the legal text.

The Economic Freedom Law also provides that the entrepreneur may not be required to compensate for or abuse or mitigate the abuse in the context of impact studies or other authorizations of economic activity. The execution or provision of any kind for areas or situations beyond those directly impacted by the economic activity, as well as unreasonable or disproportionate measures, are classified as abusive.

With this provision, the law prevents compensatory measures from being imposed on those affected indirectly, a situation very common in cases of large enterprises. However, it ensures that investments in compensatory measures will be made for impacts actually caused, making it difficult to transfer state obligations to entrepreneurs.

The authors also discussed the topic in Environmental Licensing in the Economic Freedom Executive Order, on Fausto Macedo's blog, in the newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo.