- Category: Labor and employment

The Labor Reform (Law No. 13,467/17) extended the jurisdiction of the Labor Courts to include in its list of duties decisions on ratification of out-of-court settlements (article 652, item IV, letter "f", of the Consolidated Labor Laws), based on the Voluntary Adjudication Process.

In the general judiciary, in turn, the Code of Civil Procedure of 1973 already set forth in its article 1 the exercise by magistrates of voluntary adjudication. With the enactment of the New Code of Civil Procedure, the subject gained even more prominence, with the drafting of a separate chapter on the matter (Chapter XV, in articles 719 to 770).

In the Labor Courts, the inapplicability of voluntary adjudication had as its justification the characteristics of labor relations, according to which, in theory, the employee is always at a disadvantage vis-à-vis the employer. In other words, there is allegedly a defect consent in any and all negotiations, regardless of the characteristics and the desire of the employees.

The impossibility of ratifying out-of-court settlements by the Labor Courts was certainly one of the reasons for the so-called "judicialization of labor relations."

Since employers had no assurances about the enforceability of out-of-court settlements (as a result of the alleged unwaivability of labor claims), it was common practice to bring "strike suits" or so-called "sham litigation" in association with employees. This occurred mainly in cases of workers with a higher hierarchical level as a way of guaranteeing the effectiveness of settlements to resolve conflicts in a definitive manner, without the possibility of future surprises on any other subject. In other words, security was sought.

This procedure was repudiated by the Labor Courts because it was understood that mock litigation was fraudulent, which could lead to denial of ratification of the settlement or even to termination of any ratification if the parties were discovered later. There was also a risk of opening of a complaint with the Brazilian Bar Association against the parties' lawyers.

The new prerogative has been regulated by articles 855-B and 855-E of the Consolidated Labor Laws, which establish that the parties may reach a settlement out of court and present it for ratification by the Labor Courts, provided that: (i) it is done by joint petition between the parties' lawyers; and (ii) the parties are assisted by different lawyers.

Except for the 15-day deadline for the judge to review the settlement, as well as the latter's option to schedule a hearing, the Labor Reform did not bring in further procedural details relating to ratification of settlements before the Labor Courts.

In view of this lack of regulations and the importance of the matter, the Higher Council of the Labor Judiciary (CSJT) chose this issue for its first public hearing, led by the Deputy Chief Judge of the Council and of the TST, Justice Emmanoel Pereira.

According to news piece published on the TST’s website, the objective is to standardize voluntary adjudication by creating a standard procedure for ratifications of out-of-court settlements at a national level. Thus, the CSJT seeks to provide a general guideline for all Labor Courts.

In this sense, and considering the broad adherence by parties (more than 600 settlements since November of 2017), the Judicial Center for Consensual Methods of Dispute Resolution of the Circuit Court of the 2nd Circuit (Cejuscs-JT-2), the body responsible for ratification together with the judges of the Labor Courts, was a pioneer in providing guidelines to be followed in the assessment of the Voluntary Adjudication Process:

- Requirements for the complaint: The filing brief must contain identification of the contract or legal relationship, the obligations agreed upon (amount, time, and mode of payment), a penalty clause, items negotiated and their respective amounts, the amount in controversy, as well as assignment of responsibility for tax and social security payments.

- Listing of amounts: the complaint must list the installments subject to the settlement, thereby defining their respective legal nature, respecting the rights of third parties and matters of public policy.

- Registration in the PJe: it is necessary that the lawyers of both parties register, and it is not enough for the lawyers to sign the petitions together.

- Processing of the petition: the request for ratification of the out-of-court settlement is filed, the court sends the record to the Judicial Center for Consensual Methods of Dispute Resolution (Cejusc-JT-2), which will review the application.

- Procedural costs: The costs of 2% over the value of the settlement must be advanced by the parties and prorated among the interested parties. The collection of costs shall be determined in the order by the judge of the Cejusc-JT-2 that receives the complaint.

- Powers of the magistrate: judges may order amendment of complaints; reject complaints because of unlawful or inadmissible settlements; grant ratification; order the curing of procedural defects; or schedule a hearing for the parties to provide testimony.

- Scheduling a hearing: a hearing is not mandatory, but the Cejusc-JT-2, as a rule, should schedule one.

- Management of the hearing: the judges may preside directly over the hearings or do so through mediators, always under the supervision of the magistrate, who alone is competent to approve the settlement.

- Attendance at the hearing: when scheduled, unjustified absence of any party at the hearing will cause the proceedings to be closed, resulting in extinguishment without a resolution on the merits.

- Discharge of the settlement: discharge involving a subject foreign to the process or legal relationship not brought to court is possible only in the event of judicial voluntary settlement in contentious proceedings. The discharge must be limited to the rights (amounts) specified in the petition for settlement.

- Employment relationship: the existence of an employment relationship or lack thereof is not at the discretion of the parties.

- FGTS and unemployment insurance: no authorizations shall be issued for the release of the Guarantee Fund for Length of Service (FGTS) and unemployment insurance; it is up to the employer to assure the employee access to these benefits.

- Execution of settlements: ratified settlements are judicially enforceable instruments, and any execution due to noncompliance must be submitted to the judge of the original Labor Court, since the Cejuscs-JT-2 is only responsible for reviewing and ratifying settlements.

It is important to note that the guidelines issued by the Cejuscs-JT-2 do not have the force of law. Magistrates have the autonomy to follow different guidelines in ratifying out-of-court settlements.

In any case, within the jurisdiction of the Circuit Court of Labor Appeals of the 2nd Circuit (Greater São Paulo and the Southern Seaboard/Shoreline), the Cejuscs-JT-2 guidelines serve as important recommendations to be followed for future out-of-court settlements brought to court for ratification.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

The expansion of the power sector, one of the flagships in Brazil's infrastructure, has been assured in recent years by investments obtained in several auctions of new, existing, and reserve energy held by the Federal Government through the National Electric Energy Agency (ANEEL) and the Electric Energy Trading Chamber (CCEE). The authorizations or concessions granted in these auctions conferred upon various agents the right (and responsibility) to develop power generation projects for delivery under commercialization contracts also resulting from the auctions. These documents follow the format of an Electric Energy Trading Contracts in the Regulated Environment (CCEARs), between generators and distributors, in the case of new and existing energy auctions, or Reserve Energy Contracts (CERs), between generators and CCEE, in the case of reserve energy auctions. In both cases, after the results of the public tenders are ratified, a search for sources of funding begins in order to enable the development of the projects and the generation and delivery of the power purchased. In this context, a fiduciary assignment of the receivables originating from the CCEARs or CERs of the project receiving the financing is used as collateral in almost all financing transactions. The manner for formalization and perfection of this type of collateral is already well established and involves the execution of a collateral agreement, filing it with the appropriate registry of deeds and documents, and sending notifications regarding the fiduciary assignment to the counterparties purchasing the energy (power distributors, in the case of CCEARs, and CCEE, in the case of CERs). The notifications have two main objectives: (1) informing the counterparties of the creation of a lien over the receivables with a fiduciary assignment in favor of the creditors; and (2) instructing the counterparties to direct payments due under the contracts to the escrow accounts indicated by the creditors. In addition to sending these assignment notices, it is also important to follow the procedure for changing the payment instructions under CCEARs and CERs, established by CCEE, an entity that, among other duties, is responsible for implementing rules for electric energy trading contracts and mechanisms. In order to change the banking data provided in CCEARs and CERs, an electronic form generated and made available by CCEE, upon the agent’s request, should be filled out, pursuant to Module 3, Sub-module 3.2, of the CCEE Trading Procedures (approved by ANEEL through Order No. 1,454/2016 and updated by Order No. 1,911/2017). Specifically with regard to CERs, it is also necessary to obtain CCEE’s prior consent in order to conduct a fiduciary assignment of receivables arising therefrom. Consent is required under the terms of the CERs themselves and must be requested by following the procedure established by CCEE in a document complementary to Sub-Module 3.2, mentioned above, issued in August 2017. Based on the CCEARs used in the latest energy auctions, the distributors' consent is not required for the fiduciary assignment of receivables therefrom.

- Category: Litigation

A novelty brought in by the New Code of Civil Procedure (NCPC), the chapter regarding partial dissolution of companies presents some controversies that we propose to analyze in this article, as we point out in summarized form below.

I- Partial dissolution of corporations

The first innovation of the NCPC is in its article 599, which expressly authorizes partial dissolution actions also for a “privately-held corporation", provided that the shareholder or shareholders holding at least 5% of its share capital demonstrate that it "cannot fulfill its purpose" (paragraph 2). This is a novelty of a material nature, insofar as both the Civil Code and the Brazilian Corporations Law provided only for the possibility of total dissolution of corporations, in accordance with what was previously determined by the Commercial Code and the Civil Code of 1916. The provision has already been subject to criticism because procedural law does not lend itself to governing substantive law, and such inclusion is outside the norm. Moreover, if a company is not fulfilling its purpose, that would relate not only to the dissenting partner, but to all partners. Therefore, the question should be treated as a scenario for total dissolution, and not partial, as provided for by the Brazilian Corporations Law. In any case, the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) has already had the opportunity to issue a judgment recently whereby it admitted, for example, the partial dissolution of a corporation that, in twelve fiscal years, only generated profit in three and distributed dividends in one of them. While the legal provision has received criticism for supposedly going beyond what it should, it is also the target of objections for having fallen short of what it could. This is because, for more than a decade, case law has admitted the possibility of partial dissolution of certain corporations with intuitu personae, privileging content over form. These are, for example, family businesses, usually of a small or medium size, styled as a corporation, but often with evident affectio societatis. However, the NCPC was silent on this point, having lost the opportunity to govern a scenario that had long been consolidated by case law.

II - Criteria for determination of assets

The criterion for determination of assets is possibly the point that most interests those involved in a partial dissolution of a company. In accordance with the Civil Code and the Draft Commercial Code, the NCPC determined that the provision contained in the articles of association would be observed. However, in spite of an express provision in this sense, it is not uncommon for case law to relax this point on the grounds that it considers a particular contractual provision to be unconscionable, or even asserting that the criterion chosen in the articles of association would only prevail in the event of consensus. However, in the event of omission in the articles of association, the NCPC establishes that the equity criterion for the determination of assets should be observed through a determination of the balance sheet, which should consider not only tangible assets but also intangible assets. This is a material change in relation to the provisions of the Civil Code, which, despite setting forth the equity criterion, is silent regarding the consideration of intangible assets. However, it is important to be alert to a tendency in case law to also relax this provision. Although most decisions comply with the provisions of the NCPC, many assert that the equity criterion cannot be adopted in isolation. They thus determine that the discounted cash flow method be observed after a determination of the balance sheet.

III - Date of dissolution of the company

Finally, attention is drawn to item IV of article 605 of the NCPC, which establishes as the date of dissolution of the company, in the event of judicial exclusion of a partner, the date of “a final and unappealable decision to dissolve the company." Notwithstanding the commendable effort by the legislator, the new rule, in practice, causes more harm than good. Unfortunately, conditioning the determination of assets on a final and unappealable judgment not only opens up space for perpetuation of the conflict but also for the possibility of manipulating the best date for a determination of assets by means of successive appeals. Given this, one has already observed a certain relaxation of the legal provision by case law, not least because article 607 allows for review of the date and the criterion for determination of assets, provided that "at the request of the party, at any time before the commencement of the court-appointed expert’s examination." The state courts, for example, have already set the date of dissolution as being the date of service of process in the suit or the sending of a notice stating the evident breach of affectio societatis. As summarized above, the NCPC did well to discipline partial dissolutions of corporations, a gap that was felt in the previous law. However, the aforementioned chapter has already been the subject of controversy, since it brought in innovations of a material nature and failed to explicitly set forth provisions governing issues that, in practice, had already been defined. Thus, we have it that, as before, one can expect that case law will have the role of answering questions on the matter.

- Category: Labor and employment

- Category: Litigation

Because of its economic and strategic relevance to national security, port activity has always been conducted exclusively by the Federal Government through legal and contractual relations, sometimes marked by conflicts, with concessionaires, permit holders, and other companies authorized to perform public services.

For years, the disputes in the sector were settled exclusively by the Brazilian Judiciary, which implied a delay in the resolution of these controversies, thereby hindering the renewal of contract and making the continuity of investments in infrastructure difficult. To solve these problems, Law no. 12,815 (the Ports Law), which governs the direct and indirect operation of ports and port facilities by the Federal Government, was enacted in 2013.

Among the innovations brought in by the Ports Law, paragraph 1 of article 62 allowed disputes relating to debts (namely, those debts listed in the head paragraph of the same article) of port concessionaires, lessees, licensees, and operators to be settled through arbitration, pursuant to Law no. 9,307/1996 (the Brazilian Arbitration Act).

The specific regulations on the application of arbitration to the port sector came with Decree no. 8,465/2015, which, although subject to some criticism, represents a significant stimulus to the adoption of arbitration by the Public Administration in the port sector, since it regulates important issues such as objective arbitrability, publicity, choice of arbitrators, and institutions, among others.

Decree no. 8,465/2015 provides for the possibility of debating, in the context of an arbitration, issues related to defaults on contractual obligations by any of the parties, as well as port charges and other financial obligations of the port concessionaires, lessees, licensees, and operators vis-à-vis the port’s administration and the National Waterway Transportation Agency (ANTAQ) (article 2).

It is also provided that disputes related to the recomposition of the economic and financial balance of contracts will be resolved by arbitration, but Decree no. 8,465/2015 restricts access to arbitration in these cases by establishing that the matter can only be subjected to arbitration by a submission agreement, signed after dispute has arisen (that is, it cannot be covered by an arbitration clause - article 2, II).

Decree no. 8,465/2015 also allows conflicts already brought in court to “migrate” to arbitrations, through the drafting of an arbitration agreement (article 9, paragraph 4). In addition, it is possible to extend the duration of contracts while an arbitration is pending, provided that the legal and regulatory requirements are met and provided that the party contracting with the Public Administration: (i) has paid in full the undisputed amounts due; (ii) has paid or deposited an amount corresponding to the amount in dispute; and (iii) undertakes to pay the entire amount that it may be ordered by the arbitral tribunal to pay within a time limit not to exceed five years (article 13).

Although Decree no. 8,465/2015 provides that the Brazilian Arbitration Act should be applied to arbitration proceedings arising in the port sector, some rules included in Decree no. 8,465/2015 represent important modifications to the Brazilian Arbitration Act and, therefore, create a different procedure for port arbitrations from the procedure applied to arbitral proceedings in general under the Brazilian Arbitration Act.

Among the novelties included, the text (i) establishes that cases involving more than BRL 20 million will be settled by at least three arbitrators (article 3, V); (ii) grants both parties a minimum time period of 45 days to submit their respective defenses (article 3, VI); (iii) in an obvious violation of party equality, imposes on private parties the burden of advancing all expenses for the arbitration proceedings, even if the arbitration is initiated by the Public Administration (article 3, VII), in which case the contracting party will only be entitled to reimbursement if the Public Administration is defeated (article 12); and (iv) bars the payment of legal fees by the defeated party (article 3, IX).

Arbitration under Decree no. 8,465/2015 may be institutional or ad hoc (article 6, paragraph 4). However, the preference is for the management of the proceeding by an arbitral institution, and the option for ad hoc arbitration is considered an exception and must be justified. Institutional arbitration will necessarily be administered by a Brazilian chamber (article 4, paragraph 2).

After more than two years since the enactment of Decree no. 8,465/2015, it is still not possible to determine whether the changes it brought in fact contributed to greater efficiency in the resolution of conflicts related to the port sector, especially since there are still no precedents on the issue.

Since its enactment, only one arbitration has been initiated based on Decree no. 8,465/2015. The case involves Libra Terminal S/A, the terminal operator of the Port of Santos, in São Paulo. In September 2015, Libra Terminal S/A signed a submission agreement along with the Government, through the Secretariat of Ports (SEP), and the State of São Paulo Docks Company (Companhia Docas do Estado de São Paulo - CODESP), with the assent of ANTAQ.

The signing of the agreement, which represented the parties’ withdrawal from nine lawsuits (some of which had already been pending for 15 years) was very well received, as it was considered a landmark in arbitration involving the Public Administration.

However, after more than two years, CODESP has not even appointed its representative in the case, which involves more than BRL 1 billion and is pending before the Center for Arbitration and Mediation of the Chamber of Commerce Brazil-Canada (CAM-CCBC).

Thus, arbitration in the port sector is still a blank canvas. This indicates that the excessive bureaucracy created by Decree no. 8,465/2015 makes proceedings slow and may even discourage parties from resorting to arbitration to settle port disputes.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

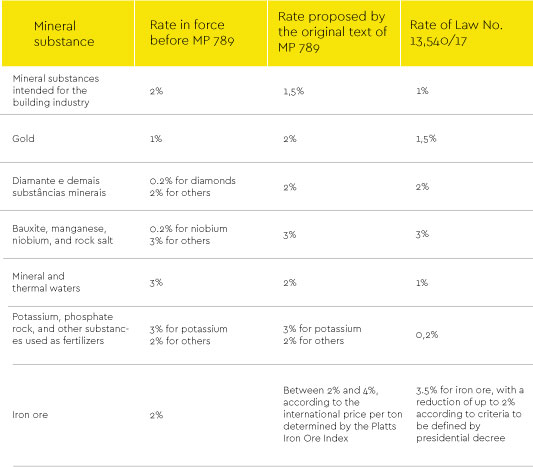

After lengthy discussions, at the end of November the Federal Senate approved two presidential decrees that alter the legislative environment of the mining sector. MP 789, which modifies the rules of Financial Compensation for the Exploration of Mineral Resources, CFEM, and MP 791, which creates the National Mining Agency to replace the National Department of Mineral Production. The final texts of Conversion Bills Nos. 38/17 and 37/17, submitted for presidential approval, were finally converted, respectively, into Laws No. 13,540/2017 and 13,575/2017, published in the Official Federal Gazette on December 19 and 27. The proposal approved by the Senate and converted into Law No. 13,540/2017, which deals with CFEM, generated since the publication of its original text in July 2017 (in the form of MP 789), severe reactions on the part of companies and experts in the sector, who claim that the new structure for collection of CFEM greatly increases the costs of a sector already heavily burdened by taxes. Among the changes approved, we highlight:

- the change in different CFEM rates:

- expansion of the calculation basis for CFEM, which is no longer calculated based on net sales (subtracted from expenses with transport, insurance, and sales taxes), but rather on gross revenue, with taxes applicable to marketing and sale deducted.

President Temer, upon approving Law No. 13,540/2017, exercised his prerogative of veto for two material provisions. The first veto resulted in the exclusion of "municipalities socially impacted by mining activity" among those that would be entitled to a share of the CFEM, on the grounds that the criterion "socially impacted" is too subjective. The second veto excluded the point two percent (0.2%) rate proposed for the extraction of gold and diamonds under the framework mines, previous stones, and colored cuttable stones, in addition to limestone as a soil corrective, potassium, rock salt, phosphate rocks, and other fertilizers, these materials being subject to the rate described above. The reason for the veto, according to the President’s office, was that reduction in the tax rate would result in a significant loss of resources for part of the municipalities that are entitled to a share in the CFEM, in addition to impacting on the transfer to the Federal Government, constituting a renunciation of revenue without an indication of compensatory revenue. The new law also brought in changes that have resolved various legal clashes over the last few years in a manner favorable to the government and to the detriment of companies. An example is the obligatory collection of CFEM when purchasing mineral assets at public auction. The new law also innovated when defined mining waste and tailings resulting from the exploration mining rights as mineral goods for CFEM collecting purposes. The CFEM rate applied to these mineral assets will be halved if the tailing is used in other production chains. It is also worth mentioning the adoption of a mechanism to define the base price for minerals by the sector's regulatory agency in order to guarantee a higher value-added calculation basis for collection of CFEM at the time of transactions transferring between establishments of the same company, or from the same economic group. This same mechanism also provide that the CFEM will apply at the time of consumption or effective sale of the mineral asset, another topic that may lead to new debates, given the difficulty of delimiting the new concept of consumption brought about by the legislative change, as well as the various stages related to the industrial transformation of mineral goods. MP 791, converted into Law No. 13,575/2017, in turn, sets forth the creation of the National Mining Agency, a federal agency that replaces the former National Department of Mineral Production, DNPM. Although the agency is still below the Ministry of Mines and Energy, the measure was positive since it aims to amend a previous legislative distortion that allowed the creation of an agency for each of the main economic sectors (telecommunications, with ANATEL, oil and gas, with the ANP, electric power, with ANEEL, among others), but left out the mining sector. Although it was well regarded by participants in the industry, the mere creation of a new agency, with the absorption of staff and budget of the predecessor agency, does little to alter the regulatory and oversight panorama of the mining sector, which lacks investments to supply retained work demand, especially in the light of new environmental and rules and regulations for mining dams in response to the Mariana accident. It is a consensus that if the agency's regulations are not accompanied by an increase in its budget allocation for new contracts and modernization of its equipment and systems, the measure may have little impact. The decree that will regulate the new agency and detail its regulatory limits is still pending publication, as well as is the definition of its budget. The new Law No. 13,575/2017 has already been published with some expansion of the DNPM's previous regulatory allocation. However, the decree that will regulate the new agency should detail its role, which will determine whether its new duties will be able to remedy the existing flaws in the actions of the predecessor agency. Lastly, MP 790, issued by the president together with the two others presented here and, in fact, the only one of the presidential decrees that dealt with material changes in the current Mining Code, did not succeed in the National Congress. The text was not voted in due time by the National Congress and lost its effectiveness, which represented a defeat for participants in the mining sector who defended its approval as essential for legal security brought about by the set of presidential decrees and for the necessary modernization of the current regulatory framework. The uncertainty in the sector is therefore maintained as to possible new legislative changes in the future and the understanding of a considerable part of the investors and agents in the mining sector is confirmed to the effect that the government’s measures were predominantly for revenue purposes, without any relevant upside for the industry.

- Category: Labor and employment

Law No. 13,467/2017 (the Labor Reform) eliminated the obligatory nature of ratification of termination of employment contracts by the trade union representing the category or the Ministry of Labor and Social Security (MTPS) for employees with more than one year of service. With the repeal of the provision, regardless of the duration of employment, no termination of employment after the entry into force of the Labor Reform is subject to any type of ratificfation as a validity requirement, except for cases in which the collective bargain agreement applicable to the category so establishes. Because of this change, many questions have been asked about the procedures for withdrawing FGTS, since in the period prior to the Labor Reform, the Termination of Employment Agreement (TRCT) ratified by the competent entity (trade union and/or MTPS) was considered requirement to the process. There is even news of an impediment to withdrawal of FGTS by workers without the submission of a duly ratified TRCT. In order to resolve doubts and avoid controversy over the collection procedures, Caixa Econômica Federal changed its "FGTS Manual - Movement in Restricted Accounts", which became established as mandatory documentation for withdrawing deposits:

- For termination of employment contracts formalized as of 11/11/2017: original and copy of CTPS, provided that the employer has reported to Caixa Econômica Federal the date/code of movement for Social Connectivity or in the Form for Termination Collection.

- For termination of employment contracts formalized before 11/10/2017: TRCT duly ratified.

The established transition rule provides that, for terminations formalized after the entry into force of the Labor Reform, the worker must only submit the CTPS, but it is the duty of the employer to correctly report to Caixa Econômica Federal the date/Social Connectivity movement code or the Form for Termination Collection. It is important to note that the employer's failure to comply with this obligation will make it impossible for the employee to withdraw FGTS, giving rise to complaints and inquiries by competent bodies, including the Labor Courts. Therefore, the requirement should be rigorously and correctly observed.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Among the mechanisms to foment development provided for by the law, the authorization for the Federal Government to participate in a fund set up exclusively to finance specialized professional technical services that will support the structuring and the development of concession projects and public-private partnerships stands out. Subject to the framework of the State-owned Companies Act (Law No. 13,303/2016), the hiring of these professionals must be regulated by means of internal regulations on bids and contracts to be observed by the fund, including with respect to the scenarios for dismissal and unenforceability of bidding.

The fund, which will have a private nature and equity separate from that of its unitholders, will be created, managed, and represented by a financial institution controlled directly or indirectly by the Federal Government. In addition to federal entities, any individual or legal entity, public or private, under public or private law, may be a unitholder. An initial fund payment of R$ 40 million is expected, in 2017, plus R$ 70 million in each of the next two years.

In addition to the payment of units, the assets of the fund may be constituted through (i) donation from foreign states, international and multilateral organizations; (ii) reimbursement of amounts spent by the managing agent in the contracting of professional services, per the purpose of the fund; (iii) funds arising from the sale of assets and rights or from publications, technical material, data, and information; and (iv) financial proceeds obtained from the investment of its funds.

Law No. 13,529/2017 also introduces significant changes in the legal framework for public-private partnerships, the Growth Acceleration Program (PAC) and the Brazilian Agency for Guarantee and Guarantee Fund Management (ABGF). Thus, an amendment is introduced for article 4, item I, of Law No. 11,079/2004, in order to reduce the minimum amount of administrative and sponsored concessions contracted to R$ 10 million, half of that originally fixed by the PPP Law. Regarding the PAC, Law No. 11,578/2007 allows the program to benefit from the transfer of funds identified in the budget law as of the type “remnants to be paid", whether or not inserted via parliamentary amendments. Finally, the scope of the ABGF was expanded, allowing the Infrastructure Guarantee Fund to cover risks in public-private partnerships even when contracted by municipalities, and not only by the Federal Government and the states, per the initial version of Law No. 12,712/2012.

In short, the conversion of MP 786 complements the list of regulatory tools available to the public administration to stimulate privatization processes. Since projects modeled on concessions and public-private partnerships are only able to attract investors when properly structured from a technical-operational, economic-financial, and legal-institutional point of view, a new standard of quality is expected in the next call for proposals to be published, especially by the states and municipalities.

- Category: Labor and employment

One of the main and most important changes promoted by Law No. 13,467 (Labor Reform) is the distinction between two categories of workers: the hyposufficient and the hypersufficient. According to the prevailing understanding in the Brazilian Labor Code (CLT), all workers, without distinction, were presumably hyposufficient and, therefore, would not have bargaining power (autonomy of will) to negotiate with employers. Since 1943, the date of entry into force of the CLT, until now, however, great evolution of the social, legal, intellectual, and economic has occurred in the world. To accept that the rules adopted more than 70 years ago be applied today in the same way, without a contextualized analysis, would be to disregard all this evolution. The factual context has changed, and so have the standards and qualifications of the Brazilian workforce. We see that today senior executives have extensive CVs, national and international work history, vast professional experience, and a rich academic background. They cannot be equated with the truly hyposufficient employees, who have often not even completed basic education and for whom, with some exceptions, the rules of the CLT were drafted. With the evolution of the Brazilian economy, more complex labor relations have become common, especially in large urban centers. Often top executives, because of their technical knowledge and the strategic position they occupy in the market, have even greater bargaining power than their employers. Thinking about this, in the process of the Labor Reform, this single paragraph was included in article 444:[1] "The free negotiation referred to in the head paragraph of this article applies to the scenarios set forth in article 611-A of these Consolidated Laws, with the same legal effectiveness and preponderance over collective bargaining instruments, in the case of an employee holding a higher-education degree and who receives a monthly salary equal to or greater than twice the maximum benefit limit of the General Social Security System.” The interpretation drawn from the text above is that employees who have, at the same time, a higher-level diploma and who receive a monthly salary equal to or greater than R$ 11,062.62 (today's values), have the autonomy to (re)negotiate/loosen the provisions of their existing employment contracts in relation to the topics listed in article 611-A. Moreover, it is clear from the text that this free negotiation has the same legal effectiveness and preponderance over collective instruments. In other words, it is possible to reach the interpretation that the free negotiation between the hypersufficient workers and the companies would have the same weight as those negotiations between the union and the company. In this context, and in conducting a systematic analysis of the labor rules based on the Federal Constitution of Brazil (CRFB/88), a possible interpretation is that it would be possible, then, to renegotiate salary/remuneration with hypersufficient workers. This is a syllogism, as explained below. According to article 7, item VI, of the CRFB/88, the irreducibility of wages is a right of workers, except if provided in a collective convention or collective bargaining agreement. Article 611-A itself ratifies the understanding embodied in CRFB/88, stating that collective conventions and collective bargaining agreements prevail over the law when dealing with compensation, bonuses, and profit sharing. Considering that the sole paragraph of article 444 establishes that negotiations with hypersufficient employees have the same effectiveness as collective bargaining, it could be possible to argue then that workers belonging to this new category could renegotiate their salaries. Notwithstanding the possible interpretation indicated above, which will certainly arouse much debate, it is very important to have caution. Firstly, because of the scenario of great legal instability regarding the Labor Reform. Presidential Decree No. 808/2017 was not even voted on and has already received more than 900 amendments. In addition, there are numerous suits of unconstitutionality filed before the STF, none of which has been reviewed thus far. Therefore, it is possible that article 444 and its sole paragraph may still undergo changes. Second, because the cut-off line differentiating hypersufficient workers established by the Labor Reform, despite representing 2% of the national population, is relatively low and does not necessarily reflect the autonomy in negotiations that article 444 sought. Although there are still no precedents in this regard, since the Labor Reform has been in force for only a month, we see good arguments to defend this negotiation in highly specific situations and for positions of extreme relevance in the companies, called C-levels, provided that such negotiation is conditioned to the granting of other advantages for the worker, such as the possibility of future variable gains, the guarantee of employment itself, among others. It is noteworthy that prevailing labor case law has already authorized, in collective bargaining, conditional reduction in salary, even temporarily. In some situations, for different reasons, monthly remuneration becomes excessively high and outside the applicable benchmark. Not infrequently, in times of crisis and reduction in demand, wages previously paid need to be readjusted to reflect companies’ new reality. It is also not uncommon for employees themselves to see this new reality and prefer to reduce their salaries to current levels and remain in their jobs rather than being fired. That is, the proposition identified in the new rules brought about by the Labor Reform constitutes an instrument capable of giving balance and security to the needs of employers and employees who are hypersufficient. Therefore, while it is necessary to be very cautious on the issue of "wage irreducibility" even for the hypersufficient, this is a debate that deserves attention in times of crisis.

- Category: Labor and employment

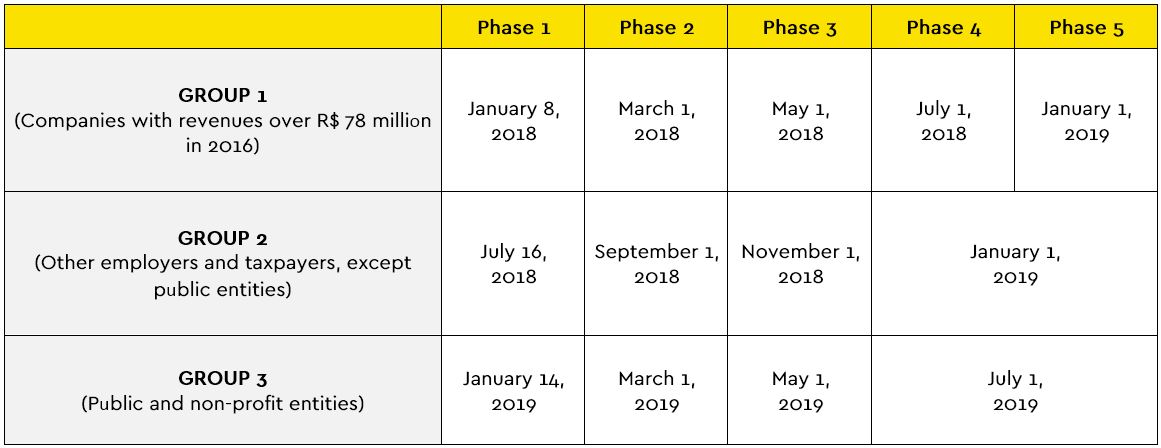

Yesterday, November 30, the Government published a new implementation schedule for eSocial, created by the Management Committee. The main purpose of the rules is to facilitate the implementation of the system by employers and to give greater certainty to the process, in response to various requests submitted by companies and class entities.

Under the new rules, the implementation of the system will be gradual, in five phases. It will begin in the first half of 2018 and should be complied by companies with revenues over R$ 78 million per year.

The entities comprising Groups 2 and 3 may choose to start using eSocial in January 2018, which should be done in an express and irreversible manner, according to regulations published in the future.

The five phases will be devoted to meeting the following obligations:

- Presentation of information related to companies/bodies, with records of data from the employer and tables containing payroll parameters;

- Presentation of information regarding employees/civil servants, their relationship with companies/bodies, and other non-periodic events (vacation, sick leave, termination);

- Submission of payroll and periodic events;

- Replacement of the GFIP form (Social Security Information Form); and

- Presentation of information related to Occupational Safety and Health.

With the implementation of eSocial, the Federal Government hopes to reduce red tape in presenting information regarding tax, fiscal, social security, and labor obligations, since they will all be gathered together in a single environment. This should reduce the number of obligations to be met by employers (eliminating obligations with the same purpose) in order to make Brazil more business-friendly.

The gathering together of information will also facilitate the supervision of companies by the competent authorities, which may cross-check the data available, without tax auditors’ having to appear at the companies or wait for them to present documents.

The expectation is that this will lead to a huge increase in the number of assessments. Therefore, companies should review their current internal policies, also considering the recent Labor Reform (Law No. 13,467/2017 and Presidential Decree No. 808/2017), in order to comply with current legislation, at risk of deemed admission to prohibited practices in providing the information required by eSocial.

It is recommended that the review of practices be started as soon as possible, taking as a lesson the implementation of eSocial for domestic employers, when there were clear complications.

- Category: Real estate

The word arra originates from the Latin arrha, whose meaning, as in the Egyptian aerb, Hebrew arravon, Greek arrabôn, and Persian rabab, which means a guarantee. A millennial institution in human relations, arras guaranteed, initially, the promise of a marriage, with the delivery, by the groom, to the person responsible for the bride or directly to the bride, an object or amount of money. If the marriage does not take place, quadruple of the amount or the thing should be restituted. Subsequently, this limit was reduced to double and replicated for other contractual relationships in order to create an obligation of compliance in the future. For a long time arras were used both to attest to the perfection of a contract and to ensure that "arranged marriages" were performed. However, with the falling out of use of contracts of arranged marriages, the institute of arras came to be applied exclusively within the scope of the obligational rights, but always carrying with itself the idea of a guarantee that the deal desired would be perfected. In Brazil, arras (or earnest money) were originally regulated by the 1916 Civil Code, in the general part on the contracts and with emphasis on its characteristic of preparation for the execution of a contract. In the 2002 Civil Code, the debts began to be treated under the law of obligations, more specifically in the section on default, containing a new characteristic: that of determining the amount of compensation in the cases of established contractual default as agreed upon by the parties. It is now possible to conclude that arras have the function of: (i) confirming the legal deal sought by the parties; (ii) pre-establishing losses and damages in the event the legal deal is not concluded; and (iii) initiating payment of the legal deal, whether in kind or by way of guarantee (in the event that a good is delivered other than that which was agreed upon for payment, such as a ring, that good must be returned after full payment). Much of legal scholarship classifies arras as confirmatory and penitential. Confirmatory arras make the contract compulsory, without the possibility of exercising buyer’s remorse. Penitential arras, in turn, allow for buyer’s remorse and serve as compensation for the injured party. As a rule, arras are confirmatory and, when the intention of the parties is to characterize them as penitential, this must be expressed in the contract. The main effect of confirmatory arras is to demonstrate that the parties are bound and rule out buyer’s remorse. If the contract is not fulfilled, the offender will be subject to penalties for non-compliance. Penitential arras also have a secondary function: to serve as compensation to the party harmed by the exercise of buyer’s remorse. In this case, they serve as the limit of indemnity expressed in the contract. In the buyer’s remorse on the part of the party who gave the arras, they are lost in favor of the other party. On the other hand, in the event that the party who received them has seller’s remorse, it will be necessary to return them in double corrected monetarily. In 1964, penitential arras were subject to restatement by the STF (Precedent 412), which established them as the limit of indemnity in contracts with a remorse provision. However, in a recent judgment (Special Appeal No. 1,669,002 - RJ 2016/0302323-0, published on October 2, 2017, of the authorship of Justice Nancy Andrighi), the STJ presented an innovative interpretation, admitting the possibility of full retention of penitential arras, even without the exercise of remorse. This was an action for rescission of a private instrument promising to assign rights to acquire real property, with a claim for damages and reinstatement of ownership, filed by the sellers. The sellers showed that the buyers, already in possession of the property, were not fulfilling their contractual obligations. The Court of Appeals of Rio de Janeiro (TJ/RJ) decided to terminate the agreement, ordered reinstatement of ownership in favor of the sellers, and authorized full retention of the arras. The arras had been determined in the contract as being penitential. Therefore, if buyer’s remorse were exercised, they would serve as a penalty to the party that withdrew from the deal. The

buyers argued that the full withholding of the arras was unjustifiable and abusive, since there was no buyer’s remorse, but simply delay in the fulfillment of contractual obligations. According to them, according to article 418 of the Civil Code, the full amount of the arras could only be fully retained in the event of exercise of buyer’s remorse by the buyers. The STJ understood that, although termination of the contract does not result from the exercise of buyer’s remorse, once the parties have negotiated the penitential arras, the effect of the indemnity must be applied immediately also in the event of breach of contract. In this sense, it upheld the lower court’s decision, having even stated that an express contractual provision to this effect is not required for the buyer to forfeit the arras. In addition, the STJ considered it reasonable to withhold more than 50% of the value of the deal, since the buyers had been enjoying and using the property for more than eight years, without any consideration to the sellers. The court opined that reduction of the arras defined by the parties in the contract would constitute, in this case, unlawful enrichment of the buyers. At a time when unlawful enrichment in analogous situations has been repeatedly rejected by the higher courts, this important precedent by the STJ deserves to be highlighted. This position in favor of enforcing contracts and maintaining contractual balance, which prizes the principle of a return to the status quo ante, is quite positive and is an advance towards greater legal certainty for parties to a contract.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

The scope of application of Provisional Presidential Order No. 800/2017, popularly known as the Highways MP, became clearer with Ordinance No. 945/2017, published by the Ministry of Transport, Ports, and Civil Aviation on November 16. Published in September of this year, the MP establishes the rescheduling of investments under federal highways concession contracts, with a view to solving the problem of concentration of investments in the first years of the concession (click here to read more about the “Highways MP”). In its explanatory memorandum, the MP shows its purpose, which, in large part, is to obtain a better conjuncture for the continuity of federal highway concession contracts, which provide for a concentration of investments at the beginning of their performance. In particular, the explanatory memorandum cites the concessions of the 3rd stage of the Federal Highway Concession Program (Procrofe), which were tendered between 2012 and 2014, whose contracts provided for the obligation to fully duplicate the road sections in five years, which, for this reason, were heavily affected by subsequent economic instability, as concessionaires faced a heavy loss of demand and liquidity, as well as great difficulties in obtaining long-term loans under the conditions stipulated at the time of preparation of the Logistics Investment Program), which could, according to the Federal Government, affect the adequate provision of public road services. It is important to emphasize that the scope of the Highways MP was not clear. As can be seen from its explanatory memorandum, the rescheduling of investments established in the MP was applicable to road concessions that included the execution of investments at the beginning of the contract, such as the concessions of the 3rd stage of Procrofe. With the advent of Ordinance No. 945/2017, the rule is now clear to the effect that the contracts that are suitable for rescheduling of investments are those that concentrate more than half the value of the investments on the execution of construction to expand capacity and make improvements in ten first years of the concession. Accordingly, Ordinance No. 945/2017, upon stipulating the term of 10 years, also includes certain concessions of the 2nd stage of Procrofe, tendered between 2008 and 2009. In implementing regulations for the Highways MP, Ordinance No. 945/2017 brought in the terms and conditions according to which the interested parties must support their requests, the documentation necessary, and other requirements for the rescheduling of investments, as well as the time limit for a response by the National Agency of Land Transport (ANTT). Facing little resistance in the National Congress by the opposition, the Highways MP, in force, in theory, until February 2018, assures federal highways concessionaires the right to request the rescheduling of the investments, provided that the requirements and conditions provided by the Highways MP and Ordinance No. 945/2017 are observed. The Mixed Committee of the National Congress, however, has already submitted 34 amendments to the MP, which, on an emergency basis, should soon be voted on to consolidate the Draft Conversion Law. Most of these amendments aim to reduce the maximum period for the rescheduling of investments, set in the Highways MP at 14 years. In line with the objective of Ordinance No. 945/2017, the Federal Government plans to avoid rescheduling of investments in upcoming federal highway tenders. To do so, it will require high initial contributions from companies or consortia winning future bids, thereby avoiding a fall in the price of tolls, in order to mitigate imbalance of contracts due to any fall in demand. Therefore, the higher the discount, the greater the initial capitalization. Ordinance No. 945/2017 and the Highways MP are inserted in a package of measures of the Federal Government for the infrastructure sector, whose purpose is to give more comfort to the market, taking into account the expectation of resumption of private investments in projects with speed, legal certainty, and transparency, even in the face of the still serious political scenario and the convalescent economic situation. What is observed so far is a positive response from investors in the sector regarding the introduction of new mechanisms for concession contracts, such as re-bidding, early extensions, and friendly terminations, which, as with the case of rescheduling of investments, bring in flexibility for the infrastructure sector and private investors and facilitate the provision of new investments.

- Category: Litigation

The case law of the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) on the issue of the government’s right to withdraw from an eminent domain action during the course of the judicial proceeding has recently changed. The issue is of the utmost importance, since eminent domain represents a form of suppressive intervention by the State in private property, and its reversal has relevant practical and legal effects. In the course of an eminent domain action, if the government understands that the reasons that motivated it no longer exist, such as public utility or social interest, it may withdraw from the proceeding and return the good to the owner. However, the STJ has established in the past some limits on the exercise of this prerogative by the public entity. More specifically, the court determined that withdrawal from the eminent domain action can only be done before full payment of the indemnity (Special Appeal 38.966/SP and Interlocutory Appeal in Special Appeal 1,090,549/SP) and it presupposes the return of the condemned property in the same conditions as the government received it from the owner. A request for withdrawal is therefore not possible when the condemned property is substantially altered by reason of occupation by the government (Special Appeal 722.386/MT). Despite this understanding, there is still doubt in the case law with respect to who is responsible for proving that the condemned property is no longer in the conditions in which it was delivered to the condemnor, thus preventing withdrawal. This uncertainty was finally settled with Special Appeal 1,368.773/MS, which decision was published earlier this year. According to the STJ's understanding, when the owner wishes to prevent withdrawal, it is incumbent exclusively on him to prove a any impediment to the exercise of this right by the public entity. The STJ's reasons follow the precepts of the Code of Civil Procedure itself in relation to the burden of subjective proof - it is incumbent upon the plaintiff to prove the facts that give rise to his right and, on the defendant to demonstrate the existence of a fact impeding, modifying, or extinguishing the plaintiff’s right. Therefore, when the impossibility of restoring the property to the previous state constitutes a fact impeding the condemnor's right, in this case withdrawal from the eminent domain action, it is the defendant property owner’s burden to prove whether this fact actually exists. In addition, according to the STJ, in this scenario there is no viable argument in favor of reversing the burden of proof to the detriment of the public entity, since granting this measure would violate due process of law, enshrined in the Federal Constitution. Finally, to force the public power to keep an asset that it does not need, because there is no longer any necessity, public utility, or social interest, would violate the public interest and the constitutional rules that discipline the institute of eminent domain. In this context, defendants in eminent domain actions must act diligently to demonstrate, through documentary evidence, testimony, experts, and other forms of evidence admitted by law, that the condemned property is somehow substantially altered and unfit for the use for which it was originally intended, which would cause the condemnor to no longer have the ability to withdraw. If the existence of an impending fact is raised and proved by the owner, there will be no alternative left to the public entity other than the continuation and conclusion of the eminent domain action, with the payment of just compensation after the final judgment in the eminent domain action. On the other hand, if it is not proved that the property has undergone significant changes that would prevent its use as prior to the eminent domain case (or if it is proved that the damages suffered are of little relevance), the owner must simply receive the property back and seek redress for damages and losses caused to the property by the condemnor in a separate suit seeking compensation. The scenario in which the eminent domain action is abandoned will normally be more favorable to the owner, since he will receive the property supposedly fit for the use he made of it before, without the need to wait for payment by the State. Only specific damages, of a relatively small amount, shall be awarded for the disturbance of quiet enjoyment caused by the public entity during the period in which it limited possession of the property. However, if the property really exhibits significant changes after the withdrawal by the public entity, it may be disadvantageous for the owner to accept the return. For this reason, he must take all the necessary precautions to fully prove, on the record of the eminent domain action, that the asset is no longer fit for the intended use. However, in adopting this position, the owner will most likely have to wait a considerable period of time to receive fair compensation. Consequently, the owner must adhere to the STJ's new understanding in agreeing to the restitution of the property, in the event that the public entity withdraws from the eminent domain action, or, if it considers this procedure not to be feasible, present in court all evidence corroborating the existence of significant changes to the asset during the possession of by the condemnor, under penalty of having to forcibly receive the property back and be compelled to seeks damages and losses by means of subsequent suit for compensation.

- Category: Labor and employment

One of the most striking and controversial changes promoted by Law No. 13,467/1207 (Labor Reform), later complemented by Presidential Decree No. 808, was the end of the obligation to pay union contributions. Also called the union tax, this contribution was collected annually from employees and companies and sent to unions, federations, confederations, trade unions, and even the Ministry of Labor. Between applause and criticism, most of the news and commentary on this change referred only to the end of employees’ obligation to contribute. In fact, the new wording of article 582 of the Consolidated Labor Laws (CLT) is clear and states that employers shall only deduct the union contribution from employees who have previously and expressly authorized collection. Article 582. Employers are required to deduct the union contribution in March of each year from the payroll of their employees who have expressly authorized in advance collection for their respective unions. However, although it received little comment, the Labor Reform also made union contribution to employers’ unions optional for companies. The old wording of Article 578 of the CLT was imperative in determining that union contributions would be "paid, collected, and applied" in the manner established. However, the Labor Reform added at the end of article 578 the expression "provided that they are expressly authorized in advance": Article 578. Contributions owed to trade unions by participants in economic or professional categories or professions represented by said entities shall be paid, collected, and applied in the manner established in this Chapter, provided that they are expressly authorized in advance. The conclusion that the union contribution will also no longer be mandatory for companies is strengthened by the new wording given to article 587 of the CLT by the Labor Reform: Article 587. Employers who choose to collect union contributions must do so in January of each year, or for those that come to be established after that month, at the time they apply to the authorities for registration or a license for the exercise of their respective activity. The end of the obligation will come into force in 2018, unless some proposed amendment to Presidential Decree 808 or a new law on this subject is enacted. It is important to note that the Labor Reform did not mention other forms of contribution to unions. Thus, there is nothing to prevent collective rules from establishing other payments to be made by companies and employees, with questionable obligatoriness for those not associated with the unions.

- Category: Environmental

The Strategic Environmental Assessment (AAE) has been causing concern among companies for some time. This is because, although this study is not legally required for environmental licensing of potentially polluting activities, the absence of the AAE has been viewed by some environmental agencies as an obstacle for the issuance of environmental licenses.

The Ministry of the Environment (MMA) defines AAEs as "an environmental policy instrument whose purpose is helping decision-makers in advance with the process of identifying and evaluating impacts and effects, thereby maximizing the positive ones and minimizing the negative ones, which a given strategic decision, regarding the implementation of a policy, plan, or program, could trigger for the environment or the sustainability of the use of natural resources, at whatever level of planning." While discussions of the concept, importance, and (in)dispensability of AAEs have advanced in recent years, it is no exaggeration to state that we still face a scenario of legal uncertainty on the issue. The scarce regulations on the study in question create a certain nebulousness due to the absence of a coherent legal framework. How can one demand a particular study if the law does not even clarify in what situations it should be required? How can one demand from entrepreneurs a macro-assessment of the environmental aspects of an entire region not necessarily related to the specific activity that they will carry out? In order to resolve this situation of uncertainty and to enable a proper environment for the effective sustainable development, it is crucial that the subject matter be explored in more depth. In order to shed light on the topic, the Federal Attorney General's Office (AGU), through the Specialized Federal Prosecutor's Office within the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (PFE-IBAMA), issued Opinion No. 00007/2017/COJUD/PFE IBAMA SEDE/PGF/AGU. The Attorney General stated, among other arguments, the following: “We emphasize that the AAE serves as support for government planning (PPP), and does not bind it nor the environmental licensing (...). The assessment of the cumulative and synergistic impacts of a licensed object is entirely possible within the environmental licensing. The measurement of cumulative and synergistic impacts is not exclusive to the AAE. This same function is present in the Environmental Impact Study (EIA), as clearly provisioned in the Conama Resolution 01/86, but is also present in other types of impact studies, since these must contextualize the environmental impacts caused, therein analyzing how the impacts of the licensed object behave in the environment, entailing, therefore a cumulativeness and synergy assessment, in proportion to their impacts. (...) What is argued herein is that an ecologically balanced environment is not adrift without the prevision of an AAE." It may be noted that the AGU considers an AAE to be a supporting and optional instrument. Thus, requiring it in the context of environmental licensing proceedings is unnecessary. According to the PFE-IBAMA, in addition to the fact that the assessment is not required by law and is directed only at non-binding orientation of public policies, its essential content (for example, the measurement of cumulative and synergistic environmental impacts) is already included in other environmental studies focused specifically on the environmental licensing of activities and undertakings, such as the Environmental Impact Study and the corresponding Environmental Impact Report (EIA/RIMA). In view of the aforementioned legislative disorientation, Draft Law No. 3,729/2004 (the proposed General Environmental Licensing Law, still under analysis by Congress) contains a chapter on AAEs and clarifies that: “Article 39: (...) Paragraph 2: The AAE cannot be demanded as a requirement for environmental licensing and not having one shall not constitute an obstacle to or hinder the licensing process." The same draft law clarifies that AAEs “shall be carried out by the agencies responsible for the formulation and planning of government policies, plans, and programs" (Article 38, sole paragraph), that is, by the Government. Although there are different understandings in Brazil, we note that currently there is a tendency in Brazil to consider AAEs to be studies attributable to the government authorities, which should guide them as a tool in decision-making for government policies, plans, and programs. AAE, therefore, are instruments that should be used even before – for the creation of – the policies. The environmental licensing, on the other hand, consists of an instrument to implement the already existing policies. Therefore, it is reasonable to argue that the duty to prepare an AAE cannot be transferred to individuals and legal entities under private law in the context of administrative environmental licensing processes. Positions to the contrary may stimulate masked arbitrariness under a false mantle of administrative discretion, thereby fostering the already acute legal uncertainty that plagues Brazil’s Environmental Law.

- Category: Tax

Advance on and reimbursement of procedural expenses

Disbursement of procedural expenses is handled by our legal system from two distinct chronological perspectives: advance (a priori, such that the act may be carried out) and reimbursement (a posteriori, with the outcome of the proceeding, according to the logic of loss of suit).

As a general rule, the parties must advance payment of expenses related to acts performed or required in the proceeding (article 82 of the Code of Civil Procedure). Thus, the plaintiff who files a suit for collection and, in this context, requests the production of expert evidence, must deposit the expert’s fees. Under this same logic, expenses with contracting for a certain guarantee, because it is a requirement for filing a motion to stay execution, must be initially assumed by the taxpayer.

At the end of the proceeding, as guidelines for reimbursement of procedural expenses, two principles are identified: that of loss of suit and that of causality.

From the rulemaking point of view, we see that the Code of Civil Procedure more explicitly addresses the reference point of loss of suit, according to which the unsuccessful party must compensate the winner for procedural expenses advanced (article 82, Paragraph 2). According to this same principle, in the event of reciprocal loss of suit (each party being partly winner and loser), the procedural expenses shall be distributed proportionally (article 86).

Specifically regarding the execution process, the content of article 776 of the Code of Civil Procedure, according to which "the judgment creditor shall reimburse the judgment debtor for the damages suffered by it when the judgment, which has become final and unappealable, declares that the obligation that gave rise to the execution was wholly or partially invalid."

Also in the Law on Tax Enforcement (Law No. 6.830/80), guidelines may be found in this regard, specifically relating to the responsibility of the Public Treasury for reimbursement of procedural expenses if it is unsuccessful in the end (article 39, sole paragraph).

Another principle is that of causality. Although there is an important zone of confluence between the principles of loss of suit and causality (in many cases, the losing party is also the party that gave rise to the demand and the costs involved), they should not be confused with each other.

The logic of causality helps to explain the duty to reimburse procedural costs (or payment of fees) on the part of the party who, although not exactly losing from the perspective of substantive law, has given cause to the procedural legal relationship and the resulting costs.

A paradigmatic situation relating to the subject of taxes should help one to perceive the distinction between loss of suit and causality. This paradigm is a tax execution to collect on a tax debt that was created as a result of an error in the filling out the Declaration of Federal Tax Debts and Credits (DCTF) by the taxpayer itself. Once the error has been found, the tax execution will have to be extinguished, with a recognition that the collection is undue, that is, with a "loss in the suit" by the Public Treasury.

However, the case law of the Superior Court of Justice (STJ), including in the context of a Special Appeal Representative of the Controversy, established that in such cases, in order to determine liability for the costs of the proceeding, it is important to investigate who caused the undue collection. If the taxpayer has filed for a rectification of the DCTF before the tax execution is filed, but the Tax Authorities, due to omission or inefficiency, failed to process it, the Tax Authorities are charged with improper filing of suit; if the evidence demonstrates that the error in filling out the DCTF submitted by the taxpayer is discovered after the filing of the tax execution, the taxpayer shall be considered the cause of the undue filing of suit and, therefore, liability for the costs of the proceeding (Special Appeal REsp 1111002/SP).

The notion of causality is the result of a construction created by case law, which ends up tempering the principle of loss of suit to the particularities of the individual case. That notwithstanding, the current Code of Civil Procedure innovates in relation to the subject by bringing in, timidly but expressly, a reference to this principle in the event of extinction of the suit due to supervening mootness (article 85, paragraph 10, of the Code of Civil Procedure). In this case, the costs of the proceeding will be borne by the party that gave rise to the filing of the suit, regardless of whether it is a plaintiff or a defendant, winner or loser from the point of view of the underlying substantive legal relationship.

May the costs of the guarantee be treated as procedural expenses for reimbursement purposes?

The technique used by the legislator in drafting article 84 of the Code of Civil Procedure is not the best, because it raises doubts, at least at a first glance at the matter, on the exemplary or exhaustive nature of the list provided therein (only procedural costs, travel expenses, and remuneration of the expert witness and per diem of witnesses are listed).

However, a systematic interpretation ends up showing that the term "procedural expenses" has a much broader scope. It is sufficient to note that Section III of Chapter II, Title I, of Book III of the Code is entitled "Expenses, attorneys’ fees, and fines" and brings in, in its Article 95, detailed provisions on experts’ fees, which are not listed in the list of expenses of article 84.

Article 98 of the Code of Civil Procedure, which deals with the gratuitousness of the Judiciary, also provides indications that the list set forth in article 84 is merely exemplary. This is because, according to the aforementioned article 98, the gratuitousness of the Judiciary is directed to the party with "insufficient resources to pay costs, procedural expenses, and attorneys’ fees." In its first paragraph, the text brings in precisely a list of costs of the proceeding subject to gratuitousness, addressing, beside the fees, a new list of procedural expenses that covers items not contemplated in article 84, such as postage stamps, expenses with publication in the official press, expenses with DNA examination, remuneration of the interpreter or translator appointed, the deposits provided for by law for lodging appeals or bringing suits, among others.

This provision mentions, among procedural expenses, "the deposits provided for by law for lodging appeals, for bringing suits, and to carry out other procedural acts inherent in the exercise of a full defense and adversarial proceedings." A guarantee offered as a requirement for filing a stay on a tax execution is similar in nature, since it is a requirement, established by law, to enable one to carry out a procedural act inherent in a full defense and adversarial proceedings (article 16, paragraph 1, of Law No. 6,830/80).

Therefore, costs with the guarantee presented as a precondition for filing a stay of the tax execution are unequivocal procedural expenses, which can be repaid, at the end, by the Public Treasury, if it is due (broadly speaking, if it is decided in the light of the principles of loss of suit and causality, that the latter will be liable for reimbursing procedural expenses).