Publications

- Category: Restructuring and insolvency

The Third Panel of the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) recognized, in the judgment of Special Appeal 1.991.103/MT (REsp 1.991.103/MT), which took place in April, the limits of the judicial reorganization court's power to decide on restraints imposed in individual executions filed by out-of-court creditors and the (im)possibility of prohibiting restraints that fall on the debtor's assets after the legal period of suspension of executions against the company in reorganization, the so-called stay period.

In an interpretation of articles 6, paragraph 7-A, of Law 11,101/05, included in the 2020 reform, and the final part of article 49, paragraph 3, of the same law, established that "the jurisdiction of the reorganization court to suspend the constrictive act carried out as part of the execution of an extrajudicial credit is restricted to that which falls solely on capital assets essential to maintenance of the business activity (...) to be exercised only during the stay period."

According to the STJ's interpretation in the judgment of REsp 1.991.103/MT, based on this new provision, it would not be possible to speak of a universal court of judicial reorganization, insofar as it would not always have the power to decide on the legality of all the acts that affect the debtor's assets.

The jurisdiction of the judicial reorganization court, according to the decision in the special appeal, would be limited to examining:

- attachments on capital goods (i.e. those directly used in the production chain) that are essential to the debtor's business; and

- the stay period of the executions referred to in article 6, subsection II, of Law 11,101/05.

At the time, the importance of equalizing the interests of creditors was highlighted who, by legislative choice, are excluded from the effects of judicial reorganization, with the principle of company preservation: "once the stay period has expired, especially in cases where a judgment granting judicial reorganization is passed, giving rise to novation of all obligations subject to the judicial reorganization plan, it is absolutely necessary for the bankruptcy exempt creditor to have his claim duly equalized within the scope of the individual execution, and it is not possible for the reorganization court to continue, after such an interregnum, to obstruct the satisfaction of his claim, based on the principle of company preservation, which is not absolute."

The aim of Law 11,101/05 is to guarantee the recovery of effectively viable business activities, by removing unviable entrepreneurs from the market as quickly as possible.

The dependence on the assets of certain creditors (the equitable owners excluded from the judicial reorganization) coupled with the inability to meet their extrajudicial obligations, even after the restructuring of debts through the judicial reorganization plan, would even create doubts as to the debtor's economic viability.

In the words of the reporting judge, Marco Aurélio Belizze, "if even after the stay period has elapsed (and once the judicial reorganization has been granted), the maintenance of the business activity depends on the use of the asset, which, in truth, is not properly owned by the company, and the related creditor who owns it, on the other hand, does not have its debt duly equalized in any other way, this factual circumstance, in addition to showing a serious indication of the unfeasibility itself of the company's recovery, completely distorts the way in which the reorganization process was designed, emptying the legal privilege conferred on bankruptcy-exempt creditors, in an unreasonable benefit to the company in reorganization and the creditors subject to the judicial reorganization."

The precedent is quite important, especially for the credit market, as it seems to indicate a welcome limitation on the understanding that the principle of company preservation would override the rights and interests of creditors. This has sometimes been the line adopted even by the STJ to submit acts of asset constriction to the judicial reorganization court.[1]

The decision in REsp 1.991.103/MT reinforces the impossibility of recurrence of cases involving companies in judicial reorganization which, after the end of the stay period, indefinitely prevent the execution of claims or repossession of assets fiduciarily sold by their bankruptcy-exempt creditors.

It was not uncommon for the judicial reorganization court to reject the rights of non-subject creditors on the basis of the application of the principle of company preservation.

Accordingly, it seems to us that the STJ's understanding expressed in the special appeal mentioned above has given Law 11,101/05 the interpretation most in line with the legislator's objectives, adequately equalizing the interests involved in a judicial reorganization.

In any case, it is still too early to predict whether REsp 1.991.103/MT will lead the STJ to consolidate this position.

It is important to monitor future STJ decisions on the subject. New judgments on the limitation of the judicial reorganization court's jurisdiction to restrict freezes ordered by the courts in which individual executions of bankruptcy-exempt creditors are being processed and the possibility of repossession of capital assets after the end of the stay period will allow us to see whether there is a consensus in the court's understanding on this matter.

[1] For example, we cite Special Appeal 1.610.860/PB, decided by the Third Panel of the STJ, and Internal Interlocutory Appeal 1.692.612/RJ, decided by the Fourth Panel of the STJ

- Category: Real estate

The Superior Court of Justice (STJ), in the judgment of Repetitive Topic 1,142/STJ, put an end to the following controversies:

- "define whether the scenario for unenforceability of collection provided for in the final part of article 47, paragraph 1, of Law 9,636/98 covers or does not cover the Federal Government's credits related to sporadic revenue, notably that related to annual land rent;" and

- "assess whether lack of real estate registration of the transaction (drawer agreements) prevents finding of taxable event of annual land rent and, therefore, prevents the flow of the lapse period for it to be levied."

In the case in question, the Federal Government lodged the respective special appeals on the grounds that the provision of article 47, paragraph 1, of Law 9,636/98 covers only periodic revenue of the Federal Government, not applying to occasional revenue, such as annual land rent.

Revenues from annual land rent, therefore, should not be included in the rule of unenforceability of the debts mentioned in the rule, according to recommendations provided in internal memoranda and opinions.[1]

The Federal Government also argued that legal transactions between private individuals allow the collection of annual land rent. Therefore, the taxable event is independent of real estate registration. The private transfers (drawer agreements) are characterized as a sufficient fact justifying the levy of annual land rent.

Finally, the special appeals argue that the initial term for counting the statute of limitations for the collection of annual land rent should be based on the moment when the Federal Government becomes aware of the taxable event.

The judgment, with the vote of the reporting justice Gurgel de Faria, partially met the Federal Government's requests, admitting that lack of real estate registration for the transaction would not prevent finding of the taxable event of the annual land rent, since, if it prevented, it would result in encouraging illegality to avoid its collection.

The decision also indicated that reading article 3 of Decree-Law 2,398/87, as amended by Law 13,465/17, could only result in the interpretation that the legislator established two alternative forms of levy: transfer for consideration of the equitable ownership of Federal Government land or assignment of rights related to it.

In addition, the request that the limitation period should start from the date of formal knowledge of the transaction by the Public Administration was accepted. In addition, it was pointed out that the topic had already been previously mentioned by the Second Panel in REsp 1.765.707/RJ.[2]

In this special appeal, the theory was established that the triggering event for counting the limitations period corresponds to the moment when the Federal Government becomes aware of the sale, instead of the date on which the legal transaction between the individuals was consolidated or, even, the date of registration of the transaction in the real estate registry.

The STJ, however, held that the final provision of paragraph 1 of article 47 of Law 9,636/98 applies to cases of annual land rent. The reason for the understanding is that the legislator did not differentiate between periodic revenue and sporadic revenue, and therefore the issue of lapse and the statute of limitations of non-taxable asset revenues of the Federal Government must follow the rules established in the provision, regardless of qualification.

In this context, from the judgment of Repetitive Topic 1,142, the interpretation that must be given to the subject was standardized, thus making it unequivocal that:

- private contracts, even without real estate registration, are facts that generate annual land rent;

- computation of lapse periods and statutory limitations periods follow the rules of article 47, paragraph 1, of Law 9,636/98; and

- the collection of the annual land rent must be limited to the five years preceding the knowledge, by the Public Administration, of the legal business entered into between individuals.

[1] Memorandum 10,040/2017 of the Ministry of Planning, Development, and Management, Circular Memorandum 372/2017-MP, Opinion 0088 - 5.9/2013/DPC/CONJUR-MP/CGU/AGU, Opinion/MP/CONJUR/DPC/N. 0471 - 5.9/2010

[2] REsp 1765707/RJ, opinion drafted by Justice Herman Benjamin, Second Panel, decided on August 15, 2019, DJe of October 11, 2019

- Category: Tax

Brazilian legislation on the taxation of investments abroad will undergo major changes if Bill 4.173/23 is approved in its entirety. These changes could impact the way Brazilian investors and companies operate and invest in assets outside the country.

To help you understand the proposals under discussion and prepare for the possible impacts, we have prepared a detailed publication covering the main points of the bill and how they may affect your investments.

- Category: Life sciences and healthcare

As of August 1, 2023, the RDC Anvisa 786/23 introduced a new health regulation affecting the operations of clinical laboratories, anatomical pathology, and clinical analysis exams (EAC). The goal is to enhance the health safety standards of these activities and to allow specific tests to be conducted in pharmacies.

Businesses have up to 180 days to comply with the new rules. To understand what changes, download our exclusive publication on the topic and stay updated with the latest guidelines in the healthcare sector.

- Category: Litigation

Faced with the overloading and congestion[1] of the Brazilian judiciary – which slows down the achievement of judicial relief and hinders access to justice – it is urgent to seek and use other appropriate methods for dispute resolution – such as negotiation, conciliation, mediation, arbitration, and dispute board.

In some situations, it is also necessary to evaluate the possibility of customization and implementation of a unique system to prevent, manage, and/or resolve a range of disputes, establishing specific procedure(s). This is the case of Dispute System Design (DSD).[2] This solution deals with systems designed to handle specific situations and needs and, for this reason, usually presents satisfactory, efficient, and fast results.

One of the most emblematic and well-known cases[3] of the DSD is the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund (VCF). This financial compensation program was created to serve the victims and families of victims of the terrorist attack that hit the Twin Towers in New York in 2001.

Through the program, more than $7 billion was paid to surviving victims and representatives of victims who died in the bombing.[4] The VCF was considered a great success, as the beneficiaries were treated fairly, with respect, dignity, and compassion, and the adoption rate was very high.[5]

Change of mindset

Before addressing the stages of the design of a dispute system and presenting examples of Brazilian cases and the benefits of the solution, it is necessary to emphasize that the adoption of this method requires a change of mindset.

The overloading of the Judiciary is mainly caused by the litigious mentality of our society and of a good part of the lawyers, for whom the best way to resolve a dispute is through state adjudication, with a definition by a trial judgment. Something that in the words of the illustrious scholar Kazuo Watanabe can be defined as the "judgment culture".

Admitting the possibility and use of new, alternative, customized, and even faster systems often faces resistance from the stakeholders involved. This is most likely because "Narcissus finds ugly what is not a mirror ...", in the words of the poet Caetano Veloso.

There is no doubt that one of the starting points for unburdening the judiciary is to use appropriate methods of dispute resolution. Developing this alternative requires less formalities and belligerence from legal professionals and more sensitivity, creativity, and flexibility. This is the mindset shift we are referring to.

Instead of stimulating litigation, lawyers need to act as negotiators, using purposeful communication, with the goal of gaining empathy and trust. They should also encourage the parties to use appropriate methods for dispute resolution and, when applicable, act as designers of a unique system to prevent, manage, or resolve a range of disputes.

The stages of designing a dispute system

According to the doctrine of Diego Faleck, the stages of designing a dispute system are:[6]

- analysis of the dispute and of the interested and affected stakeholders;

- definition of the objectives and priorities of the system;

- consensus building and system development;

- dissemination, training, and implementation of the system; and

- constant evaluation of the system.

In the first phase of the process, the appropriateness of the DSD will be analyzed. To do so, it is necessary to ascertain who the affected parties are and what the interests of each one of them are. Next, it is necessary to understand what would encourage them to seek a composition rather than litigate.

Moreover, is important to identify the damages involved in this dispute and their extent. It should also analyze the possible means or systems for prevention and/or management and/or resolution of the dispute and what the pros and cons of each of them are. Based on this information, we assess the need for and feasibility of creating a specific system for the dispute and whether this system is, indeed, the most appropriate.

In the second phase, the main goals of the system and the guiding principles to achieve these objectives are defined. Considering that the system created will be a non-binding alternative for those involved (since the judicial route, constitutionally guaranteed, will always be available), it is necessary that everyone opt for the system and, therefore, trust it.

According to Diego Faleck,[7] in order for parties to trust the system, there are six key factors:

- transparency;

- equality;

- support in objective criteria;

- efficiency;

- dignified treatment for the parties, defining worthy values; and

- government participation.

In the specific case of a compensation program, the following should also be analyzed at this stage:

- admission criteria;

- list of documents that will be required from beneficiaries;

- pricing of compensation;

- legal certainty in the system; and

- measures that can be taken to mitigate and prevent fraud, among others.

In the third stage, it is necessary to build a relationship of consensus with all the interested and affected stakeholders, including the public authorities involved, such as the Public Prosecutor's Office and the Public Defender's Office. It is of utmost importance that everyone participates in the creation process and approves it.

In addition, at this stage, the system is also developed. For this, it is necessary for the designer to select, sequence, and/or combine the appropriate methods for dispute resolution that will be used.

According to Ury, Brett, and Goldberg, there is a "dispute resolution ladder" in which different methods can be selected and sequenced as steps (the lowest-cost mechanism should be prioritized):

- prevention mechanisms (consultations and incorporation of learning from a dispute);

- interest-based negotiation (manifested in different forms);

- mediation, by peers, by an expert, in the different modalities as the case may be;

- mechanisms for returning to interest-based procedures (sources of information and mechanisms involving non-binding opinions);

- mechanisms to support the lowest cost (rights-based – variations of arbitration – and power-based – voting, limited symbolic strikes, and rules of prudence).[8]

Once the system is developed, the fourth stage begins. At this stage, the system is, in fact, put into practice, with the dissemination of information to all involved. It is explained how the system will work and who can join, among other relevant information.

Subsequently, the system is implemented and everyone who has an interest in participating joins it. Then, the procedure created is executed.

In the case of compensation programs, after entry, the legal analysis will take place. If eligible, a proposal for an agreement will be submitted, which may or may not be accepted by the interested party.

The last and fifth phase is the continuous evaluation of the system, which allows improvements to be made based on the experience with various situations that may arise during the procedure.

Cases in Brazil

After this theoretical introduction with the step-by-step to design a dispute system, we present the Brazilian cases of the DSD. All of them illustrate in an extremely satisfactory way the many benefits of a system for resolution and/or management and/or prevention of disputes for those involved – whether based on the principles of access to justice, saving time, or efficiency.

The main cases of success of the DSD in Brazil – all out-of-court compensation programs – can be divided up based on the event that led to their design:

- aircraft accidents;

- dam collapse;

- involuntary eviction; and

- socioeconomic isolation.

1) AIR ACCIDENTS

TAM Case: Compensation Chamber 3054 (CI 3054)

- Context: aircraft accident occurred on July 17, 2007 (Flight 3054, which was en route Porto Alegre – São Paulo).

- Nature of damage: moral damage and material damage.

- Public agencies involved: Public Prosecutor's Office of the State of São Paulo, Public Defender's Office of the State of São Paulo, Procon/SP Foundation and Department of Consumer Protection and Defense of the Bureau of Economic Law of the Ministry of Justice.

- Acceptance of agreements: 92% acceptance (55 proposals accepted, 3 withdrawals, and 1 proposal rejected).

- Highlight: First Extrajudicial Compensation Chamber implemented in Brazil.

Air France Case: Compensation Program 447 (PI 447)

- Context: aircraft accident occurred on May 31, 2009 (Flight 447, which flew the route Rio de Janeiro – Paris).

- Nature of damage: moral damage and material damage.

- Public agencies involved: Public Ministry of the State of Rio de Janeiro, Ministry of Justice and Procon/SP Foundation.

- Acceptance of agreements: 95% acceptance (19 proposals accepted and 1 withdrawal).

- Highlight: the complexity for directly involving a foreign company and the relevance of having the participation of the Ministry of Justice.

2) DAM COLLAPSE

Vale Case: Brumadinho Compensation Chamber (CIB)

- Context: collapse of the Fundão dam in Mariana (MG), which occurred on November 5, 2015.

- Nature of damage: moral damage, material damage, and economic damage.

- Public agencies involved: Public Defender's Office of the State of Minas Gerais.

- Acceptance of agreements: 93% acceptance (12,136 proposals submitted and 11,497 proposals accepted).[9]

- Highlight: national relevance of the accident due to the number of people affected by the disaster.

3) INVOLUNTARY EVICTION

Subsidência Maceió (AL): Financial Compensation and Relocation Support Program (PCF)

- Context: eviction occurred in five neighborhoods of Maceió (Pinheiro, Mutange, Bebedouro, Bom Parto, and Farol), due to the geological phenomenon that generated the subsidence of the soil and cracking in properties in the region.

- Nature of damage: moral damage, material damage, and economic damage.

- Public agencies involved: Federal Public Prosecutor's Office, Public Prosecutor's Office of the State of Alagoas, Federal Public Defender's Office, and Public Defender's Office of the State of Alagoas.

- Acceptance of agreements: 94% acceptance (19,501 proposals submitted and 18,356 accepted).[10]

- Highlight: the first preventive extrajudicial compensation program in Brazil, with recognition from the National Council of Justice[11].

Madre de Deus Case (BA): Eviction Program for Environmental Treatment (PDTA)

- Context: eviction occurred in Madre de Deus/BA, due to the need for environmental remediation of land owned by Colloidal Carbon Company (CCC)

- Nature of damage: material damage and economic damage.

- Public agencies involved: Madre de Deus City Government, Bahia State Prosecutor's Office, and Colloidal Carbon Company (CCC).

- Acceptance of agreements: 100% acceptance (240 proposals submitted and accepted).[12]

- Highlight: the first extrajudicial compensation program in Brazil that obtained 100% acceptance.

4) SOCIOECONOMIC ISOLATION MACEIÓ (AL)

Flexal Case: Flexais Urban Integration and Development Project

- Context: the involuntary eviction of the neighborhoods affected by the geological phenomenon (which originated the PCF), led to the socioeconomic isolation of the neighborhood of Flexais.

- Nature of damage: moral damage, material damage, and economic damage.

- Public agencies involved: Municipality of Maceió, Federal Public Prosecutor's Office, Public Prosecutor's Office of the State of Alagoas, Federal Public Defender's Office.

- Acceptance of agreements: 97% acceptance (1,578 proposals submitted and 1,533 proposals accepted).[13]

- Highlight: in addition to compensating those affected who suffered from socioeconomic isolation, the program also aims to revitalize the area, with the development of actions to promote access to public services and stimulate the region's economy and thus reverse socioeconomic isolation.

When analyzing these cases, the success of Dispute System Design in Brazil is evident, especially when we observe the following points:

- the acceptance rate of the agreements is above 90%, which demonstrates the satisfaction of those involved and the efficiency of the systems;

- speed is another highlight, especially if compared to the time of processing of cases in the Judiciary[14];

- the reputational damages of the companies involved in using the DSD are mitigated, as the company, in general, assumes the strict liability that is due to it by force of law (regardless of the actual cause of the events). This demonstrates attitude, proactivity, and good faith, which are added to the quick action in the extrajudicial solution of the conflict – always considering parameters consolidated in the case law of the Brazilian courts;

- irrevocable and irreversible discharge, as well as full compensation of the damage suffered – it is, therefore, a definitive solution;

- predictability of the amount of liability involved, since the metrics and values to be compensated are based on objective and pre-defined parameters.

The instruments of agreement entered into in the DSDs mentioned above have already been tested and endorsed by the Judiciary. Although annulment actions for a few agreements were filed, none of these actions were successful in the Judiciary – which, upon confirming the seriousness of the compensation programs and correction of the values and parameters used, accepted the solution adopted and ratified the validity of the extrajudicial agreements.

Considering all the above, although the use of a Dispute System Design in Brazil is still in an early stage, the results of the existing programs are extremely satisfactory and demonstrate efficiency, speed, and several other benefits for all involved.

Because we believe that slow justice is not justice, we are not satisfied with the statistics: they indicate that, on average, the lawsuits take around five years. This prognosis motivated us to deepen our studies in alternative and appropriate methods for dispute resolution and in Dispute System Design. Therefore, we have become enthusiastic about applying these methods, recommending them whenever appropriate.

[1] According to the Justice in Numbers Report 2022 prepared by the National Council of Justice, the congestion rate (percentage of cases not resolved in relation to the total in process, fewer new cases, plus pending cases) in the Judiciary is 74.2%. The average processing time for pending cases is four years and seven months.

[2] This is how Stanford professors Stephanie Smith and Janet Martinez define it in the article An Analytic Framework for Dispute Systems Design: "A dispute system encompasses one or more internal processes that have been adopted to prevent, manage, or resolve a stream of disputes connected to an organization or institution."

[3] The movie "How Much Is It Worth?" on Netflix tackles the subject. Trailer is available on YouTube.

[4] Information taken from the book Dispute system design: preventing, managing, and resolving conflict, written by Lisa Blomgren Amsler, Janet K. Martinez, and Stephanie E. Smith, as follows: "The VCF was closed in 2004, having paid over $7,049 billion to surviving personal representatives of 2,880 people who died in the attacks and to 2,680 claimants who were injured in the attacks or the rescue efforts . . . thereafter."

[5] Information taken from the book Dispute system design: preventing, managing, and resolving conflict, written by Lisa Blomgren Amsler, Janet K. Martinez, and Stephanie E. Smith, as follows: "In retrospect, Feinberg concluded that the VCF was very successful under the circumstances but that he would not hold it out as a standard model for no-fault public compensation. The several success factors he highlighted seem relevant to other circumstances. Claimants were treated fairly and with respect, dignity, and compassion. Participation was very high."

[6] Brazilian Arbitration Magazine -v1, n. (jul/Oct 2003) – Porto Alegre: Synthesis; Curitiba: Brazilian Arbitration Committee, 04 -v.6, n.23. Introduction to Dispute System Design: Indemnity Chamber 3054.

[7] Revista Brasileira de Arbitragem -v1, n. (jul/Oct 2003) – Porto Alegre: Synthesis; Curitiba: Brazilian Arbitration Committee, 04 -v.6, n.23. Introduction to Dispute System Design: Indemnity Chamber 3054.

[8] URY, William L Brett, Jeanne M; Goldberg, Stephen B. Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems to cut the Costs of Conflict. Cambridge: PON Books, 1993, p.41.

[9] Numbers updated Aug. 1. The program is still ongoing, so the numbers are subject to change.

[10] Official figures in news published by Braskem on August 10. The program is still ongoing, the numbers mentioned are therefore subject to change.

[11] https://www.cnj.jus.br/caso-pinheiro-a-maior-tragedia-que-o-brasil-ja-evitou/

[12] Numbers updated Aug. 21. The program has already been finalized, the result, therefore, is definitive.

[13] Numbers updated Aug. 21. The program is still ongoing, so the numbers are subject to change.

[14] According to the Justice in Numbers Report 2022 prepared by the National Council of Justice, the average processing time of pending cases is four years and seven months.

- Category: Life sciences and healthcare

Twelve months after a substantial update of the regulatory framework for medical devices, the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) continues to prioritize the revision or drafting of rules related to this category. The goal is to modernize the Brazilian regulatory environment.

More than 20 years after the previous standard (Anvisa RDC 185/01 ), Anvisa RDC 751/22, which came into force on March 1st this year, updated the requirements on the risk class, regularization, labeling requirements and use instructions of medical devices.

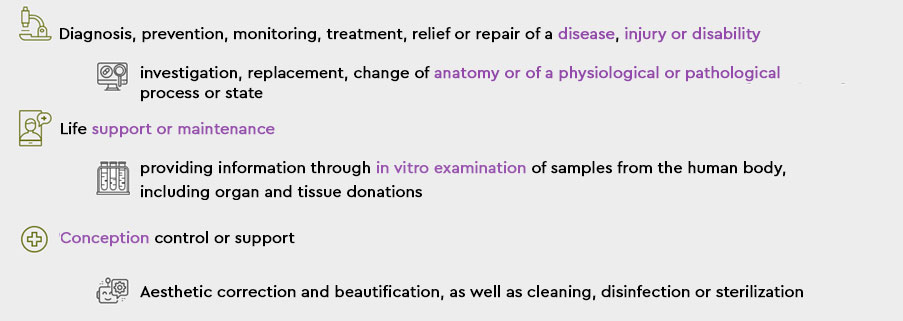

According to the new rule, medical devices (formerly called a medical product or related), are defined as any instrument, apparatus, equipment, implant, in vitro diagnostic device, software, material or other article intended for use in humans, for any of the following purposes:

The applicable framework to each product considers 22 rules that assess the risk inherent in the functionalities, purposes and mechanisms of action of each device. According to the framework, the regularization regime at Anvisa is defined: whether the request for notification or marketing authorization (MA).

Medical devices fall into two subcategories:

In vitro diagnostic medical device: reagents, calibrators, standards, controls, sample collectors, software, instruments or other articles for the in vitro analysis of samples derived from the human body, with the aim of providing information for diagnosis (or aid), monitoring, compatibility, screening, predisposition, prognosis, prediction or determination of the physiological state. Activities involving these products is also regulated by Anvisa RDC 36/15.

- Medical software (also called Software as a Medical Device or SaMD): is the product or application intended for one or more of the purposes indicated in the medical device definition and performs its functions without being part of a hardware. Can have these possible characteristics:

- run on a general-purpose computing platform (non-medical purpose); and

- be used in combination (e.g. as a module) or interaction with other products.

Medical software is also subject to specific regulation – Anvisa RDC 657/22, which sets out the processes, documents and information needed to regularize these products.

More recently, Anvisa approved the first amendment in Anvisa RDC 751/22 to regulate the situations in which the importation of products with manufacturing date prior to the regularization date in Brazil would be allowed.

In addition, Anvisa's Collegiate Board recently opened a public consultation on the use of analyses carried out by an equivalent foreign regulatory authority (AREE).

Check out the details on the topic below:

- Regulatory convergence with foreign authorities

As of September 11, Anvisa will receive contributions to the Public Consultation 1,200/23, which intends to regulate the procedure for analysis and decision of petitions for medical devices registration, using the analyzes performed by AREEs.

AREEs are defined as regulatory authorities or foreign international entities recognized by Anvisa as being of regulatory reliance. Effectively, they are institutions considered capable of guaranteeing that products authorized for distribution have been properly evaluated and meet recognized quality, safety and efficacy standards.

General rules for admission of analysis performed by AREE were recently defined through Anvisa RDC 741/22.

The rules will be applicable to medical devices classified as risk classes III and IV, as well as to in vitro diagnostic medical devices (regulated by Anvisa RDC 36/15) – except when they have been authorized by AREE through an optimized analysis process.

The main points of the draft normative instruction presented in the consultation include:

- The applicant for registration must submit the following documents: specific declaration present in the normative; document proving registration or authorization issued by the foreign authority; and the product’s instructions of use, in addition to the other documents already required in the dossier.

- Only authorities in Australia, Canada, Japan and the United States are considered AREEs.

- The optimized analysis requirement does not prioritize the petition. The analysis should be maintained according to the petitions chronological order.

Anvisa's prediction is that the new rule anticipates the analysis of 1/4 of the requests that are currently in the queue.

Contributions can be made until October 25 through an electronic form that will be available on Anvisa’s website as of September 11.

- Update of the medical device regulatory framework

Anvisa RDC 810/23, approved in August and already in force, changes Anvisa RDC 751/22. The new resolution regulates the medical devices importation with a manufacture date prior to the regularization date in Brazil.

In the past, Anvisa imposed restrictions in these cases. However, considering the absence of restriction on the matter in the Imported Goods and Products Technical Regulation (Anvisa RDC 81/09), the agency began to allow products manufactured before obtaining the MA or notification to be placed on the Brazilian market, provided that they comply with the following requirements:

- a period of five years between the manufacture and regularization dates;

- compliance with the characteristics of its sanitary regularization; and

- presentation of a declaratory document issued by the notification or MA holder, attesting the compliance with the two requirements above-mentioned, as well as attesting that the product was manufactured according to the good manufacturing practices for medical devices.

- Cybersecurity will be subject to specific regulation

At the end of 2022, Anvisa held Public Consultation 1.112/22 to discuss the essential safety and performance requirements applicable to medical devices, including in vitro diagnostic (IVD).

Now, the agency is analyzing the contributions received and should issue an updated text until the end of the regulatory agenda.

The future standard is expected to update the requirements set forth in Anvisa RDC 56/01 – recently replaced by Anvisa RDC 546/21 during the "Review" process.

It is likely that the standard also aligns with the principles and elements adopted internationally, such as: requirements related to clinical evaluation, sterilization and contamination, the environment and conditions of use, chemical, physical and biological properties, labeling, among others that are necessary to ensure the safety and effectiveness of new technologies in the regulated market.

- Upcoming discussions

Anvisa's current 2021-2023 Regulatory Agenda foresees the discussion of other relevant topics regarding the medical device industry, including:

- review of the regulation on clinical trials with medical devices (Anvisa RDC 548/21);

- preparation of a new Documentation Specification Guide for the Medical Devices Electronic Petitioning; and

- updating the standard on in vitro diagnosis medical devices (current Anvisa RDC 36/15).

The Life Sciences & Healthcare practice can provide more information about products regulated by Anvisa.