- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Liliam F. Yoshikawa, Carolina de Almeida Castelo Branco and Camila de Carli Rosellini

A new resolution of the National Mining Agency (ANM) that provides for rules regarding the Mine Closure Plan (PFM) was issued on April 30, 2021 and will enter into force on June 1, 2021. Resolution ANM No. 68/2021 presents provisions to standardize and regulate the set of procedures necessary for the monitoring of PFM throughout the life of the mine, as well as the decommissioning process of mining enterprises and post use of such areas.

Every mining enterprise, whether in force and in operation or with its activities to be initiated or suspended, must present a PFM prepared by a legally qualified professional and accompanied by the respective Technical Responsibility Note (ART).

These measures shall be complied with within certain deadlines that vary from 12 months, as of the publication of the resolution, up to 24 months from 1st june 2021, when the new rules will enter into force.

Operating mining enterprises in mining concession phase must present an updated PFM by May 4, 2021. In turn, those in mining concession request phase must submit the updated PFM within 180 days, as of the mining concession grant.

The elements that must necessarily make up the MPF to be submitted to the ANM vary according to the life phase of the mine and the start of its activities.

For projects that have just reached mining concession phase or those in the mining concession request phase which effective mining activity have not yet been initiated, the elements that should be included in the plan include:

- Maps, plants, photographs and images (standardized according to the standards of ABNT - Brazilian Association of Technical Standards);

- Documentation describing the current situation of the area;

- Mining infrastructure project overlaid to the current context of the area;

- Conceptual design of decommissioning of civil structures and physical and chemical stabilization of the remaining structures;

- The rehabilitation actions of the area already performed;

- Main monitoring and maintenance actions already planned in the area; and

- Physical-financial schedule of pfm, integrating pre-closing, closing and post-closing actions.

In the case of mines in exhaustion closure, in addition to the same elements for projects in the application phase or mining concession with activity not initiated, the PFM should contain:

- Characterization of the area of the enterprise, with data from civil structures, geotechniques, hydraulics, electrical installations, equipment, among others (standardized according to ABNT standards);

- Assessment of the risks arising from the closing of the enterprise and ways of mitigating any damages resulting from the activity;

- Plan for the demobilization of the facilities and equipment that make up the infrastructure of the enterprise;

- measures to prevent unauthorised access to facilities and to prohibit access to hazardous areas;

- Maintenance actions and monitoring of the remaining structures after the closure of the project; and

- Guidelines for adequacy of the area to the predicted future use.

For mines that are closed before exhaustion, the PFM must contain:

- Declaration of remaining mineral resources and reserves and

- Technical and economic justification for the closure of mining activities.

Finally, for operational mines, all previous elements and the life expectancy of the enterprise will be required.

In the case of projects containing mining tailing dams, the PFM should have, as a mandatory element, the tailing dam decharacterization plan or other technical solution in charge of the technical responsible, with the objective of reducing the Associated Potential Damage (DPA)[1] to each existing tailing dam.

If it is not possible to mischaracterize the tailing dam, the PFM should provide for its monitoring in accordance with current legislation. In such cases, for the preparation of the PFM, the professional responsible for the plan must be legally qualified to provide services related to tailing dams and present the respective ART.

Just as the mining activity itself and the consequent useful life of a mine are subject to variations that depend on various economic and climatic factors, the PFM should also be updated to be consistent with such changes. In this sense, the rule was inserted that the PFM should be updated every five years or at the time of updating the Economic Recovery Plan (PAE), the one that occurs first. Exception is made in the case of undertakings with mining assets with validity of less than five years and/or with the expected closure of mining activities of less than two years. In the latter case, it is mandatory to prove the execution of the PFM.

In addition to the elements mentioned above for each case, depending on the life phase of the mine, pfm updates should include:

- Description of the closing actions of the areas that may be closed throughout the operation (in the case of progressive closure) and

- Updated planialtimetric survey of the areas and structures that make up the enterprise.

Such updates shall be reported to the ANM within the deadlines set out above and be available at the mine in case of inspections.

The latest PFM update should be communicated to the ANM at least two years before the expected mining closure and, in case it takes place before exhaustion, the updated PFM should be presented. In the same sense, the waiver of the mining title may only be approved after approval by the ANM of the final report of implementation of the PFM.

Small enterprises, with proven mining and processing operations of low complexity and impact, may be exempted by the ANM from some of the elements required for the PFM.

With the measures established, the resolution reinforces the tightening of standards related to the protection of health and public safety in mining activities and the need for adequate planning of the closure of mining structures, through monitoring and monitoring of the life of mines and their decommissioning.

[1] According to the definition of Federal Law No. 14,066/2020, which amends the National Dam Safety Policy: "Damage that can occur due to disruption, leakage, infiltration into the ground or malfunction of a dam, regardless of its probability of occurrence, to be graduated according to the loss of human lives and social, economic and environmental impacts."

- Category: Litigation

For years, the matter of how the Public Treasury should behave when becoming aware of the bankruptcy of a legal entity that has a tax enforcement proceeding n(s) against it pending trial was discussed.

Several legal controversies have arisen regarding the possibility of submitting tax credits to the pool of creditors instated by the bankruptcy decree, in accordance with the provisions of Articles 186 and 187 of the National Tax Code (CTN) and article 29 of Law No. 6,830/80 (Tax Enforcement Law). There was also debate about what would be the ideal outcome for the tax enforcement proceeding – termination or suspension – in the event that the Public Treasury chooses to file a proof of claim before the bankruptcy court.

In May 2020, when judging the Special Appeal (REsp) nº 1,857,055 involving the bankrupt airline Vasp, the 3rd Panel of the Superior Court of Justice (STJ) understood that the fact that the Treasury filed the tax enforcement before the decree of bankruptcy would not prevent it from opting for filing a proof of claim within the bankruptcy proceeding. In this decision, it was understood that Article 187 of the CTN does not represent an impediment to the proof of claim, but rather a prerogative of the public entity, who can choose between tax enforcement and bankruptcy proof of claim. However, once opting for the proof of claim, it would be necessary to suspend the tax enforcement.

The 4th Panel of the STJ has a similar understanding, thus consolidating the understanding of the 2nd Section of the STJ on the issue.

The Group of Reserved Chambers of Corporate Law of the Court of Justice of São Paulo, adopting the understanding of the 2nd Section of the STJ, published on January 16, 2020 the Enouncement XI, determining that "the Public Treasury´s option to file a proof of claim to collect its tax credit within bankruptcy proceeding does not require the termination of the tax enforcement proceeding, provided that it proved it has suspended the tax enforcement proceeding in regard to the bankrupt entity". The statement is currently under review, as recently released by the state court.

Although it admitted the possibility of the Public Treasury to file a proof of claim even with the existence of a previous tax enforcement, the 1st Panel of the STJ understood that it would not be necessary to suspend or terminate the tax enforcement proceeding. Both judicial measures could run simultaneously , provided that there was no act of constriction in the tax proceeding. According to that decision, the mere existence of a tax enforcement would not be a guarantee of receipt of the claim due to the public treasury, so that there would be no bis in idem, i.e. the two options would not be being admitted simultaneously.

Little was said about what subjects would be processed and judged by the bankruptcy court, if the Public Treasury decided to file the proof of claim and suspend the tax enforcement proceedings. In other words, would the bankruptcy court have the competence– or even the expertise necessary – to assess matters that would, until then, be assessed by the tax enforcement court, such as the existence, legitimacy and enforceability of the tax credit?

Based on the original wording of Law No. 11,101/2005 (Law of Recovery and Bankruptcy), jurisprudence and doctrine did not address this theme. Marcelo Barbosa Sacramone, however, had an understanding on the subject. For him, if the National Treasury waived the privilege of maintaining its tax enforcement proceeding and chose to file the proof of claim before the bankruptcy court in order to collect its credit in a quicker manner, the bankruptcy court would then become competent to asses and rule on any matter – including the analysis of merit – that involved that credit.[1]

The wording of the new Article 7a of the Recovery and Bankruptcy Law, included by Law No. 14,112/2020, seems to clarify the issue by creating a proper mechanism for tax credits´ proof of claim.

In addition, Paragraph 4, items I and II of Article 7a, delimits which topics related to tax credits would be of the bankruptcy court´s competence, and which would be of the tax enforcement´s competence[2].

In line with the CTN and the Tax Enforcement Law – article 5 of which determines that the competence to asses and rule on the enforcement debt of the Public Treasury registered in the overdue tax debt roster excludes that of any other , including the bankruptcy court – the competence to rule on the existence, if the debt is demandable and the value of credit will be of the tax enforcement court. In other words, the analysis of the merits of the tax enforcement will not be assessed by the bankruptcy court, but by the tax enforcement court.[3]

It is up to the bankruptcy court to rule on topics such as calculation and classification of claims, in addition to those related to the collection of assets, disposial of assets and crditors´payment.[4]

Paragraph 4(V) of Article 7a – in view of the competence of the tax enforcement court to assess the matter mentioned above – states that "tax enforcement proceeding will remain suspended until the bankruptcy is terminated, exception made to the possibility of pursuing co-liable parties."

Despite the changes introduced by Law No. 14,112/2020, which entered into force on January 23, 2021, the 1st Section of the STJ, in May of this year, unanimously referred to trial under the rite of repetitive appeals REsp 1.891.836/SP, theme 1,092, with the following thesis at issue: "Possibility of the Public Treasury filing a proof of claim regarding a tax credit which is subject to an ongoing tax enforcement proceeding".[5]

Although the National Treasury has suggested that the thesis should not be made in relation to proof of claims made after Law No. 14,112/2020 came into force – considering that it expressly included the possibility of filing a proof of claim even if there is already an ongoing tax enforcement proceeding –, Minister Gurgel de Faria (rapporteur for the appeal) considered that this issue should be dealt with when the merits of the legal question are examined. Thus, currently, the outcome of the subject is awaited.

[1] "If you waive this privilege and file the proof of claim before the bankruptcy court, the bankruptcy court becomes competent for the assessment of all matters involving that claim. The justification is that the privileged treatment of the tax credit is guaranteed so that it continues with tax enforcement, so that only that judgment can assess the various issues involving that claim, such as prior payment, the absence of the obligation or possible compensation.

However, in order to accelerate its satisfaction, the Treasury could waive the privilege of maintaining its tax enforcement proceeding and choose to file the proof of claim before the bankruptcy court . With the waiver, it would allow all questions to be assessed by the bankruptcy court itself, so that it can define whether and by what amount the credit should be enforced. What cannot occur, however, is the bis in idem, i.e. having your credit paid by two different choices. The proof claim, if submitted after the filing of the tax enforcement, must be terminated, for lack of interest to act. This is because there can be no overlap of forms of satisfaction."

SACRAMONE, Marcelo Barbosa (Comments to the Business Recovery and Bankruptcy Act. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2018, p. 83.

[2] It is necessary to clarify that there are still no judgments facing this issue, due to the fact that Law No. 14,112/2020 is recent and has entered into force only at the end of January 2021.

[3] SACRAMONE, Marcelo Barbosa. Comments to the Business Recovery and Bankruptcy Act. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2021, p. 121.

[4] The issue of the constriction of assets was also the subject of Theme 987 of the STJ - "Possibility of the practice of constrictive acts, in the face of a company in judicial recovery, in the case of tax enforcemente of tax and non-tax debt" – which, however, lost its object due to the new provisions of the Recovery and Bankruptcy Law brought by Law No. 14,112/2020.

[5] Also, unanimously, it was decided to suspend special appeals at second instance and/or in the Superior Court related to this subject.

- Category: Competition

In recent trial sessions, the Court of the Administrative Council of Economic Defense (Cade) discussed whether the non-establishment of administrative proceedings to investigate alleged anticompetitive crimes reported by the signatories of leniency agreements would prevent them to obtain the certification of proper execution. Leniency Agreements are an important instrument for Cade'senforcement, especially for the investigation of collusive practices that are difficult to detect, such as cartels.

Cade’s General Superintendence (“CADE/SG”)is the body responsible for signing the Leniency Agreements, while the Cade Court is responsible for verifying if the agreement was executed in accordance with its terms. Once the Court certifies that the agreements were properly executed, it confirms the benefits sought by the signatories: the termination of Cade's punitive action or the reduction of applicable administrative penalties, as well as the extinction of the punishability of crimes related to cartel practice.

In the case examined, which runs under secrecy, the rapporteur councillor considered that the Leniency Agreement could not be certified as executed, sinceits content was not able to assist in the investigation of the reported anticompetitiveacts. In his opinion, the opening of an administrative proceeding to investigate the unlawful acts reported would be a consequence of the contributions made by the signatories during the investigation phase conducted by Cade’sGeneral Superintendence.

The rapporteur explained that the evidence brought by the signatories was uncompelling and that there were others that could have generated a different outcome from the filing of the administrative inquiry based on the information provided by the signatories. The rapporteur did not discriminate such evidence because of the secrecy of the procedure, but he mentionned,as an example, ongoing procedures in the Federal Prosecutor's Office that could have been presented by the signatories.

Accordingly, the rapporteur voted against the certification of the execution of the Leniency Agreement, on the gorunds that the signatories did not produce sufficient evidence for the administrative inquiry to result in the openingof an administrative proceeding able to investigate and punish alleged anticompetitive acts.

Another counselor of the Cade Court disagreed, understanding that, in fact, it would be up to the General Superintendence to evaluate the evidence offered when signingthe leniency agreement and to conduct investigations based on the information brought by the signatories.

According to the counselor, the signatory is not aware of the entire evidential set of which the General Superintendence has at the time of the signingof the agreement, so that it cannot foresee the repercussions of the evidence brought by him or her in the investigations promoted by the General Superintendence. Other members of the Cade Court stressed that it is up to the General Superintendence to establish minimum standards of proof for the signingof leniency agreements, and it also hasthe prerogative to examine such evidence, not the Cade Court.

In view of this discussion, the plenary, by a majority, certified that the leniency agreement was properly executedAlso, the Court established that the upcoming decision of the General Superintendence not to open an administrative proceeding would not be a reasonnot to certify its execution.

The plenary decision highlighted Cade's concern not to transfer the burden of the investigation’s results to the signatories of the Leniency Agreement, who would have fullfiledall the obligations under which they commited themselves to deliver all documents and information available to them about the facts reported.

- Category: Tax

As a result of Law No. 13,988/20, which regulates the tax transaction provided for in the National Tax Code (art. 171)[1], the Federal Revenue Service of Brazil (RFB) and the Attorney General's Office of the National Treasury (PGFN) signed, on April 18, 2021, notice of a new modality of transaction by membership, which involves social security contributions and to other entities and funds on profit sharing (PLR), in breach of Law No. 10,101/00.

Although tax transactions are already foreseen and regulated for situations which, in accordance with the definition contained in the legislation, involve unrecoverable and difficult claims, this is the first time that the Union has elected a specific litigious thesis to enter into a transaction with the taxpayer, regardless of the possibility of recovery of the claim.

The new transaction modality will have as scope administrative or judicial processes that deal specifically with:

- PLR-Employees: interpretation of the legal requirements for the payment of PLR to employees without the incidence of social security contributions and

- PLR-Directors: legal possibility of payment of PLR to directors not employed without the incidence of social security contributions.

According to information available so far, the taxpayer who opts for the new mode of transaction shall indicate all tax debts that see the legal controversy in reference, in addition to irrevocably and irrevocably confessing to be debtor of said debts, giving up the respective administrative and judicial discussions and renouncing the claims of law on which they are founded.

It is important to emphasize that those who adhere to the new modality should be subject to the understanding given by the Tax Authorities to the legal controversy transuded, including in relation to future or unconsummated generating facts, a measure that aims to end discussions on the subject.

The agreement may be formalized between July 1 and August 31, 2021. The procedures and resources of this transaction will be centralized in the e-CAC system (cav.receita.fazenda.gov.br), if the debt is linked to RFB, and on the Regularize portal (www.regularize.pgfn.gov.br), if the debit is linked to the PGFN. The taxpayer must give consent to the sending of communications to the tax domicile.

Payment can be made within five years, applying the Selic fee. The discounts granted will be applied in a regressive manner, focusing on principal, fine, interest and charges, depending on the number of installments paid. Initially, it is necessary to pay 5% of the tax debt without reductions, which can be divided into up to five successive monthly installments. The applicable discounts are indicated in the table below:

| Installment | Initial installments (no discount) | Number of additional parcels | Discount percentage |

|

Up to 1 year

|

5% of the total value in 5 installments | 1 to 7 | 50% |

| Up to 3 years | 8 to 31 | 40% | |

| Up to 5 years | 32 to 55 | 30% |

The processes with judicial deposit require special attention, because, according to the notice, the agreement to the transaction will imply the automatic conversion of deposits into union income, and the above payment terms will be applied only to the remaining balance of the debt.

It is also noteworthy that the adhering to the tax transaction does not imply the release of the taxes resulting from the bearing of assets, fiscal injunctive relief and the guarantees provided administratively, in the actions of tax execution or in any other legal action. Such exemption will occur only after the discharge of the tax debt.

The notice also brings the obligations to be assumed by the adherent, which involve transparency about their economic situation, maintenance of fiscal regularity and before the FGTS, maintenance of solvency before the Tax Authorities, among others.

Considering that this is a legal thesis Contested and which involves significant amounts, there is expectation in relation to the evolution of the theme to reduce litigation.

[1] Art. 171. The law may provide, under the conditions it establishes, to the active and passive persons of the tax obligation to enter into a transaction that, through mutual concessions, imports in dispute determination and consequent extinction of tax credit.

Single paragraph. The law shall appoint the competent authority to authorize the transaction in each case.

- Category: Real estate

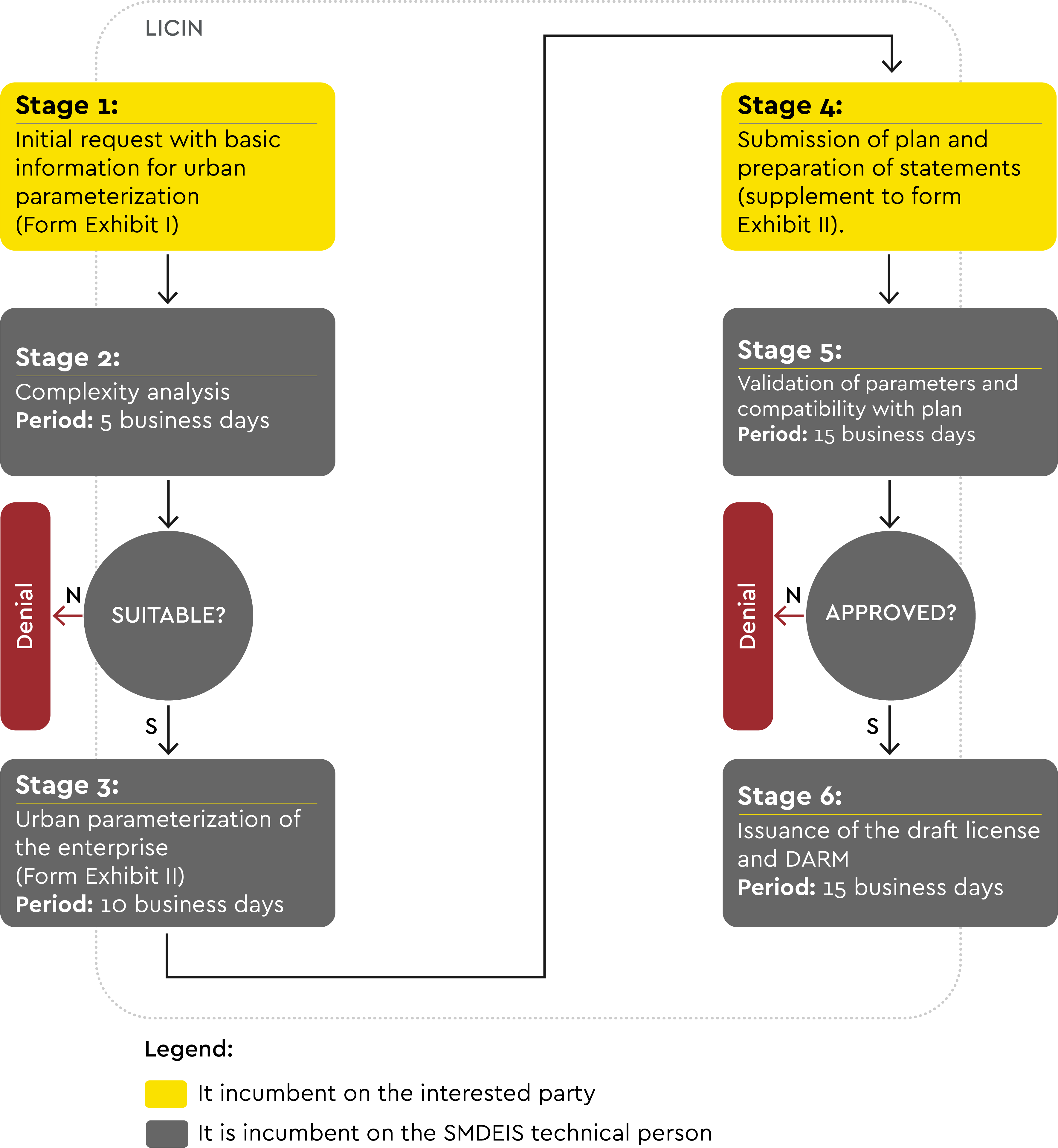

As part of the #InvistaNoRio campaign, an initiative of the Municipal Bureau for Economic Development, Innovation and Simplification (SMDEIS) to boost business in the city of Rio de Janeiro, Municipal Decree No. 48,719/21 was published on April 6, which provides for the Integrated Building Licensing (Licin) procedure and aims to cut the red tape for applications for urban permits for new construction in the city.

The procedure previously took up to one year, but since April it has been possible to obtain project approval within 30 business days (excluding the deadline for issuing the license by the bureau after approval). The initiative promises to attract more investments for the city in the construction sector and the real estate market, since the delay in licensing was one of the main obstacles for companies in the business operating in the city.

The objective was to unify and simplify the stages of the licensing process in the city. Most of the information needed for the project, for example, was self-declared by the professionals responsible for architectural design (PRPA) and the execution of the works (PREO). According to the standard published, full compliance with the parameters and requirements of the Rio de Janeiro Master Plan, the Land Parceling, Use and Occupation Legislation, the Municipal Simplified Works, and Buildings Code and other urban planning legislation and technical standards in force at the municipal, state, and federal levels was also under the responsibility of the same professionals, together with the interested parties.

From now on, the procedures for approving architectural plans should observe the following steps:

- Submission of the initial application by the applicant, by means of a form accompanied by the documentation provided for in the legislation;

- Evaluation of the information declared by the interested partyto identify non-conformities and classification in Licin;

- Filling out a new form by SMDEIS technical personnel, with an indication of the parameters required by the legislation;

- Supplementation of the form by the responsible professionals and the interested party, with an application for approval of architectural plan, accompanied by presentation of the plan;

- Approval and validation of the fulfillment of the planned parameters and their compatibility with the plan presented by SMDEIS technical personnel; and

- Issuance of the license draft and form for payment of the municipal fee through DARM.

As the diagram below shows, the steps described in the items 2, 3, 5 and 6 are the responsibility of qualified SMDEIS technical personnel and shall be carried out within the deadlines illustrated below. The fulfillment of requests and requirements must be done by interested parties within 30 business days, under penalty of cancelation.

All plans that were already in progress may migrate to the Licin procedure, provided that the steps described above are covered. This migration must be done at the request of the applicant in writing.

As an exception, plans for buildings of great complexity are not subject to the above deadlines, as well as those involving buildings or groups with more than 500 units, buildings protected by heritage protection, which depend on the payment of consideration or grants tied with obligations, among other criteria[1] defined in SMDEIS Resolution No. 10, of February 1, 2021.

In such cases, the plan should be submitted at the opening of the process due to the need for a specific analysis. However, after the necessary authorizations and/or consents from the responsible agencies have been obtained, the plans of buildings of great complexity will be able to follow the same steps provided for other constructions. Documents proving authorizations must be submitted together with the data and information provided in the first stage of the Licin process.

Article 5 of Municipal Decree No. 48,719/21 also provides that the construction license via Licin will be issued upon presentation of the protocol number formalized in the agencies whose response is required for licensing. Its validity will be conditional on the assent of such agencies. Once all the requirements are met, the license must be issued, setting the maximum period of three months for the presentation of the agreement of all agencies, which may be extended until the works begin, according to the declaration regarding the phase of the work. The works may not begin until the cancellations are obtained by the applicant.

Once the building permit is obtained, the interested party will be responsible for reporting in the administrative process of the Licin procedure the dates of commencement of the works, completion of foundations, the first slab, and, finally, the works, when inspection will be carried out for the purposes of issuing a certificate of acceptance of works (commonly called Habite-se).

Given that the new decree came into force on the date of its publication on April 6, construction companies and the real estate market should already comply with the new rules for future ventures and may migrate the ongoing licensing processes to the Licin procedure.

Although the speed of the processes depends on the actions of the other bodies not subordinate to the City of Rio de Janeiro, the expectation is that the approvals for architectural plans with application of the Licin procedure will facilitate the performance of the real estate business in the city of Rio de Janeiro.

[1] Plans of great complexity are considered to be: (a) groups of buildings with more than 500 units, including integrated groups; (b) lots included in more than one urban zoning and/or subject to bands of influence with parameters different from those applied in the remainder of the lot; (c) lots that are in locations devoid of urban infrastructure and requiring execution of an urbanization consent; (d) land parceling projects; (e) projects involving assets that are subject to heritage protection or preserved projects in any sphere; (f) projects involving processing of investiture; (g) sites where the application of projected alignments (PAA) generates inconsistency in analysis; (h) projects that require specific environmental analysis, such as: (h.1) located on the beachfront; (h.2) found within or bordering environmental conservation units, except APA; (h.3) imply removal of plant cover subject to authorization and/or management of wild fauna; (h.4) depending on prior use, point to possible contamination of the land; and (h.5) intervention in areas of permanent preservation, as defined by Federal Law No. 12,651, of May 25, 2012; and (i) projects that depend on payment of consideration or a grant imposing an obligation for licensing.

- Category: Banking, insurance and finance

Bruno Racy, Roberto Kerr Cavalcante Bonometti and Frederico Antelo

The agribusiness sector and financing alternatives for the agribusiness chain have been the subject of important changes and improvements in the last year. The conversion of Executive Order No. 897/19 (the Agro MP) into Law No. 13,986/20 brought about various innovations aimed at stimulating access to credit, especially through capital market funding. Among them, the following stand out:

- the establishment of the Solidarity Guarantee Fund;

- the creation of collateralized rural assets;

- the institution of the Rural Real Estate Note (CIR);

- the expansion of the parties authorized to issue Rural Product Notes (CPR) to include rural producers (whether individuals or legal entities), cooperatives, and associations of producers that act in the production, marketing, and industrialization of rural products, as well as the possibility of indexing the security to exchange rate variation; and

- the possibility of creating and executing real guarantees on rural properties, including through payment in kind or otherwise.

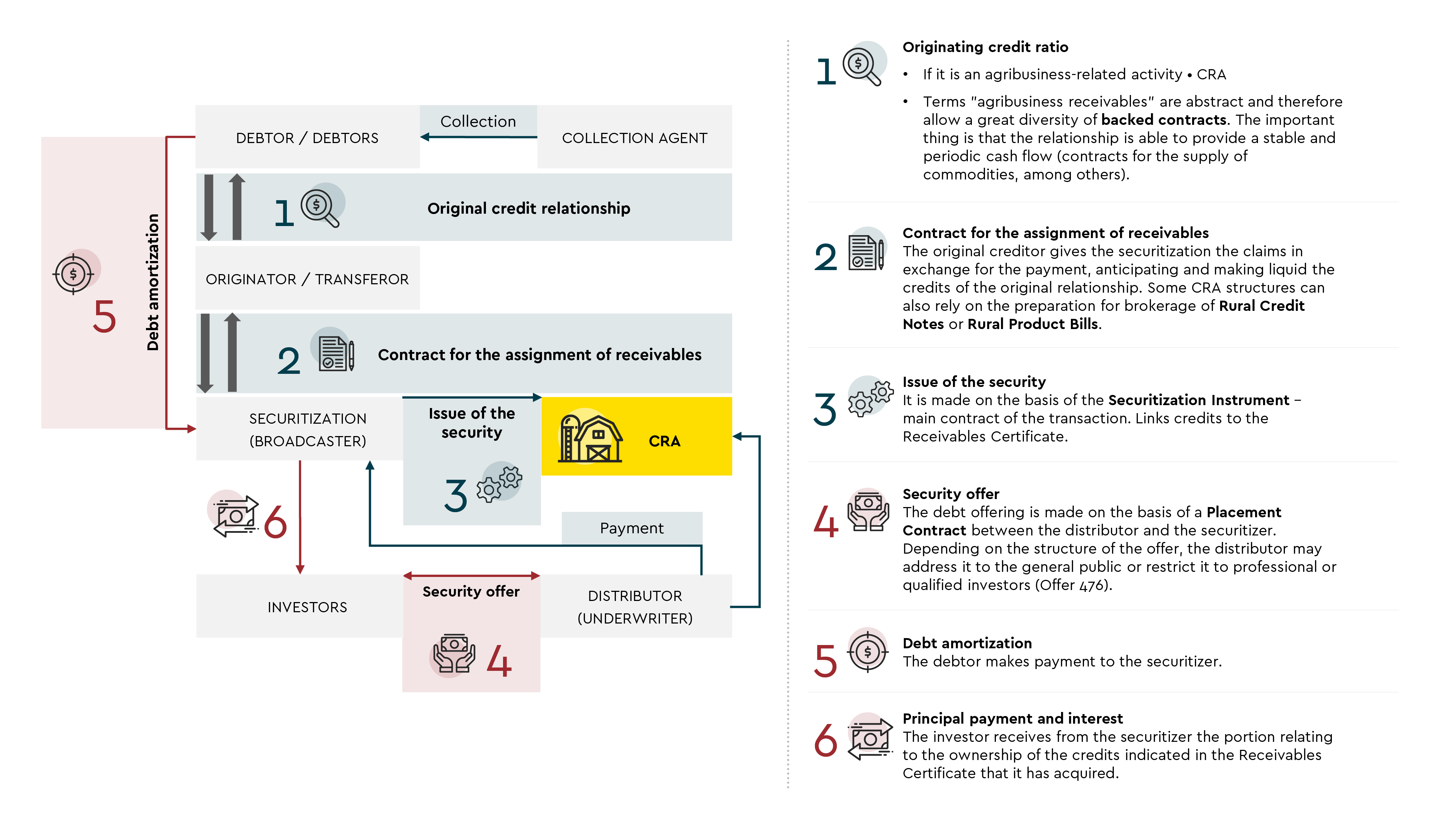

These advances have had a strong effect on the Agribusiness Receivables Certificate (CRA) market, which has been very heated in the last year. According to Anbima data (Brazilian Association of Financial and Capital Markets Entities), in 2020, 586 issuances were conducted for public distribution of CRA, totaling approximately R$ 95.8 billion. This corresponds to a 31% increase in the volume of issuances and a 21% increase in the number compared to 2019.

CRAs are fixed income securities issued by a securitizer and backed by receivables originating from business between farmers, or their cooperatives, and third parties. These businesses include financing or loans related to the production, marketing, processing, or industrialization of products, agricultural supplies, or machinery and implements used in agricultural production, as provided for in Article 23, paragraph 1 of Law No. 11,076/04.

The diagram below summarizes the structure of a CRA issuance:

Article 3, paragraph 4, of CVM Instruction No. 600 establishes that receivables rights may be considered to back (or securitize) an offer of CRA when created: (i) directly by debtors or original creditors characterized as rural producers or their cooperatives, regardless of the destination to be given by the debtor or the transferor to the funds; or (ii) debt securities issued by third parties linked to a commercial relationship between the third party and rural producers or their cooperatives; or (iii) debt securities issued by farmers or their cooperatives. This provision of CVM Instruction No. 600 reflects various CVM precedents regarding Law No. 11,076/04, through which the interpretation of credits that may contain CRA offers, including those that are at the end of the agribusiness production chain, has been expanded.

In addition to the nature indicated above, these receivables rights can be used in various ways, such as trade acceptance bills, Rural Product Notes (CPR), Promissory Notes (NP), Agribusiness Credit Rights Certificates (CDCA), debentures, Export Credit Notes (NCE), Export Credit Bills (CCE), Supply Contracts or Rural Real Estate Notes (CIR).

The CRAs market tends to become even more attractive to investors after the creation of CRA Garantido [Collateralized CRA] on April 8. It is a new product through which the National Bank for Economic and Social Development (BNDES) will act as a guarantor for investors in a CRA issuance.

The operation that inaugurated this product was the issuance of CRA from Ecoagro – a securitization firm specialized in agribusiness – based on receivables rights of Cotrijal Cooperativa Agropecuária e Industrial, with 7,700 more cooperative members.

In the case of the issuance announced, BNDES guaranteed only the CRAs of the first series (through an endorsement of the bank), which will be considered senior in relation to the CRAs of the other series, so that they will have priority (a) in receiving the remuneration; (b) in payments arising from extraordinary amortization and/or early redemption, as the case may be; (c) in the payment of the unit par value; and (d) in the event of separate equity settlement.

In the event of late payment, non-compliance with obligations, and/or if it is necessary to re-compute the escrow accounts in which the agribusiness receivables rights that backed the issuance are deposited, the fiduciary agent (as a representative of the holders of the CRAs of the first series) or the issuer may notify BNDES to make payment of the principal and interest due.

Bndes' intention with this new product is to guarantee the payment of the securities to investors and, with this, to promote access to the capital markets by small and medium-sized rural producers. With the unprecedented participation of BNDES as guarantor in the scope of CRA offers, the expectation is that this measure will result in:

- reduction in the financial costs of operations for rural producers and/or their cooperatives, since the guarantee given by BNDES mitigates the risk of default and, consequently, allows allocation of lower interest to the securities;

- greater security for those who invest in CRAs and, consequently, more interest in these securities, since, unlike LCAs (another fixed income instrument used to regulate exposure to the agribusiness sector), CRAs are not guaranteed by the Credit Guarantee Fund;

- complementing the alternative sources of financing for rural producers, or cooperatives, with more incentive to raise money in the capital market outside the traditional financial system; and

- stricter compliance with social and environmental standards, since it is a fundamental requirement for BNDES’

In line with the growing support of investors and funders for ESG analyses, another strategy to further increase the attractiveness of CRAs is the possibility of obtaining environmental and social certifications, such as green bonds or social bonds. In such cases, CRAs undergo a certification process by entities such as the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), which establish the criteria for issuing these certifications. By attracting investors who would not initially be interested and increasing demand for such securities, these certifications may also lead to reduced financial costs for the operation.

The constant growth of agribusiness, driven, among other factors, by the various forms of stimulus given to the sector, and now added to BNDES' performance as guarantor and the possibility of certification of CRAs as green bonds, makes the option of financing through these securities an increasingly interesting alternative for rural producers, as such structures tend to attract more investors.

- Category: Tax

Applications for mandamus are widely used to litigate tax issues, and are found to be attractive for their swift processing and the absence of costs for loss of suit. On the other hand, there are a number of procedural issues that must be carefully assessed in order for applications to be effective, such as pre-established evidence, their own individual time limits, and the applicable rule of jurisdiction, which deserves specific comments.

Traditionally, mandamus is sought against the functional head of the authority deemed abusive, identified as the party responsible for the act contested. In federal tax matters, this authority is usually the office of the Federal Revenue Service of the taxpayer’s tax jurisdiction. This is safe conduct, aligned with the general rule of jurisdiction established in the Code of Civil Procedure and with the principle of the natural judge (article 5, III, of the Federal Constitution).

Often, there is concomitance between the location of the government authority and applicant, which facilitates application of the rule of jurisdiction. However, there are cases where the localities are different, or when there are even different parties involved subject to differing jurisdictions, which adds complexities in identifying the competent venue and in the conduct of proceeding.

The case law on the subject has matured, mainly under the purview of the First Section of the Supreme Court, which is abandoning the current that limited the jurisdiction to assess an application for mandamus to the location of the government authority.[1]

According to the understanding that is developing in the High Court,[2] the jurisdiction over applications for mandamus brought against an act committed by a federal public authority must follow the list of Article 109, § 2, of the Federal Constitution,[3] which assigns to the applicants the power to choose among their domicile, the Federal District, or, further, the place of the act/fact that gives rise to the claim.[4]

The change was driven by the judgment in RE No. 627.709/DF, handed down by the Supreme Court under the system of general repercussion (article 543-A, § 1, of the Code of Civil Procedure of 1973). This leading case discussed the application of Article 109, § 2, of the Federal Constitution federal authorities. The doubt lay in the fact that the provision expressly dealt with "cases brought against the Federal Government", without any mention of the indirect public administration, of which the municipalities are part.

In that judgment prevailing position was that the objective of the constituent assembly in introducing the constitutional provision in question was "to facilitate access to the judiciary for parties when litigating against the Federal Government", which would have better conditions to litigate in a venue other than its head office, considering its organizational structure and the procedural advantages which it enjoys. Because it believes that these same premises apply to federal authorities, the Supreme Court acknowledged that they are also subject to Article 109, § 2, of the Federal Government.

While it is possible to consider the judgment of the leading case in question to have driven the renewal of the case law of the Supreme Court, as even previously the Supreme Court had already recognized the possibility for applicants to choose the venue of their domicile to file an application for mandamus.[5]

In those decisions, the logic prevailed that the rule of jurisdiction would apply to any and all actions brought against the Federal Government, including mandamus actions. As the Constitution made no distinction regarding the nature of the actions brought against the Federal Government, it would suffice for it to be a defendant for the applicant to choose one of the jurisdictions provided for in Article 109, paragraph 2, of the Federal Government.

In this jurisprudential framework, the First Section of the Supreme Court has applied the rule of jurisdiction of Article 109, § 2, of the Federal Constitution to mandamus actions, recognizing the right conferred on applicants to opt for the jurisdiction of their domicile.

Among the judgments dealing with the subject, the judgment of CC No. 153,878/DF, which, when dealing with a topic with a focus on mandamus actions, clarifies that this provision " does not distinguish between the various kinds of actions and procedures provided for in the procedural legislation, which is why the fact that it is a mandamus action does not prevent the applicant from choosing, among the options defined by the Constitution, the most convenient venue for the satisfaction of their claim. The constitutional order, in this respect, aims to facilitate access to the judiciary for parties litigating against the Federal Government".

It is curious to note that, when applying the constitutional rule under analysis, these judgments deal with the possibility of filing in the claimant's home, failing to address the other scenarios also mentioned in the constitutional provision. The highlight here is the possibility of filing in the Federal District, as an alternative to the place of domicile.

Although this choice is also supported by the prevailing reasoning, the topic is not addressed by this perspective, which allows questions as to whether there is effective matching of all the constitutional options mentioned therein.

On the subject, the First Section of the Federal Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit[6] has already positioned itself in the same sense as the understanding established by the Superior Courts, reaffirming the option conferred on applicants to opt for the venue of their domicile when the federal public authority is sued. However, as in the precedents of the Supreme Court, the issue has been mostly faced in the light of the applicant's domicile, without addressing the other scenarios provided for in Article 109, § 2, of the Federal Constitution (place of the act or fact that originated the claim, where the thing is located, or in the Federal District).

It is undeniable that this jurisprudential change represents a real advance in favor of access to justice and tends to evolve to clear the possibility for the claimant to choose, strategically, the place where he intends to file the action, whether in his home or even in the Federal District, to the detriment of the traditional position that suit should be brought in the place where the functional office of the authority whose act is being contested is located.

[1] AgRg no AREsp 721.540/DF, AgRg no MS 21.337/DF.

[2] CC 169.239/DF, AgInt no CC 163.905/DF, CC 166.116/RJ, AgInt no CC 153.878/DF, AgInt no CC 154.470/DF, AgInt no CC 148.082/DF, AgInt no CC 153.724/DF, AgInt no CC No. 153.138/DF, AgInt no CC No. 149.881/DF, AgRg no CC No. 167.534/DF, CC No. 163.820/DF.

[3] Art. 109. Federal judges are responsible for hearing and deciding: (...)

- 2 - The cases brought against the Federal Government may be apart from the judicial section in which the plaintiff is domiciled, where the act or fact that gave rise to the claim or where the thing is situated, or even in the Federal District. (...)

[4] The current Code of Civil Procedure has a similar guideline in the sole paragraph of its article 51.

[5]AgRg at RE 509.442/PE, AgRg no RE 599.188-AgR/PR, RE 171,881/RS.

[6] cc 1037291-51.2020.4.01.0000cc 1027286-67.2020.4.01.0000cc 1030723-19.2020.4.01.0000.

- Category: Labor and employment

The new Procurement Law (Law No. 14,133/21), enacted on April 1, aims to regulate the procurement processes and contracts of the Public Administration. The law, in force since its signing, repealed some provisions of the current legislation on the subject (Law No. 8,666/93) and will replace it completely in two years.

Among the various changes that the law regulates, some bring about impacts for labor relations. Similar to the prior legislation, the new law establishes that the responsibility for labor charges is exclusively that of the contractor and cannot be transferred directly to the Administration in case of default. However, by filling a gap that existed before, the new law regulates the scenarios in which the Public Administration may be able to respond secondarily for default on labor obligations by the service provider.[1]

Thus, the new legislation expressly establishes the possibility of secondary liability of the Public Administration for labor charges arising from the provision of continuous services with a regime of exclusive dedication of labor, provided that proven failure to monitor the fulfillment of the obligations arising under the contract.

This understanding was already adopted by the Labor Judiciary, as established by subsections IV and V of Precedent 331 and by the Supreme Court (STF) in a theory with recognized general repercussion (Topic 246), but still did not find an express legal provision.

In addition, the legislator added to the normative text some measures that the Administration may take to ensure compliance with labor obligations by service providers and, consequently, avoid possible liability for labor charges arising from the contract.

In this sense, when hiring companies providing for the execution of continuous services, the Administration may require, through a call notice or contract, various preventive measures for the fulfillment of labor obligations, such as:

- requiring security, bank guarantee, or performance bond, with coverage for defaulted severance payments;

- conditioning the payment provided for in the contract on proof of discharge of labor payments by the contractor;

- making deposits of the amounts arising from a contract in an unattachable escrow account;

- paying severance funds directly to the workers, with subsequent deduction of the amounts related to the contract; and

- establishing that the amounts intended for vacations, thirteenth salary, legal absences, and severance pay for employees of contractors who participate in the performance of the services contracted, will only be paid by the Administration to the contractor when the triggering event occurs.

The measures implemented by the new legislation indicate that the contracts entered into by the Public Administration for the provision of continuous services will be safer and allow preventive control of procurements, imposing on the private sector stricter conditions for fulfillment of labor burdens.

[1] "Article 121. Only the contractor shall be responsible for labor, social security, tax, and commercial charges resulting from the performance of the contract.

- 1 - Default by the contractor in relation to labor, tax, and commercial charges shall not transfer to the Administration the responsibility for payment thereof and may not burden the object of the contract or restrict the regularization and use of works and buildings, including before the registration of real estate, subject to the scenarios provided for in paragraph 2 of this article.

- 2 - Exclusively in the hiring of continuous services in an exclusive arrangement of provision of labor, the Administration shall be jointly and severally liable for social security charges and secondarily for labor charges in the event of proven failure to monitor the fulfillment of the obligations of the contractor."

- Category: White-Collar Crime

Law No. 14,133/21, also called the New Public Bids and Administrative Contracts Act (NPBAC), brings several legislative changes to replace the provisions of Law No. 8,666/93. In the criminal sphere, the bidding crimes, previously provided for in Articles 89 to 99 of Law No. 8,666/93, were fully transferred to the Penal Code, through the inclusion of Articles 337-E to 337-O in Chapter II-B: "Crimes against public bids and administrative contracts".

In addition to the relocation of crimes from extravagant legislation to the Penal Code, the description of typical conduct has undergone modifications that can generate significant changes. Some of them directly impact the description of criminal conduct, such as the of the crime of defrauding a public bid or contract, which now includes the following conducts as criminal:

- the delivery of goods or services with quality or in quantities other than those provided for in the notice or in the contractual instruments

- the supply of goods unusable for consumption or with expired shelf life; and

- changing the service provided.

That is, the new law included in the list of criminal conducts some that had long been processed, although they did not expressly appear as bidding crimes.

On the other hand, the crime of disreputable contracting, which provided for equal punishment for the admission, participation and hiring of a disreputable company or supplier through a public bidding process, has now segregated the conducts by injury. Thus, for mere admission or participation in bidding, the penalty will be more lenient than in the case of hiring, which seems more reasonable in the light of the principle of culpability in criminal law. The old wording placed in the same position agents who committed conducts with different harm degrees and who, therefore, deserve a different penalty that is proportional to the impact of their conducts.

Other changes modified solely the penalty imposed and not the description of the criminal conducts, however, these subtle changes can generate important procedural consequences that affect the statute of limitations, the rite in which criminal proceedings will be processed, the possibility of negotiating prosecutorial agreements and replacing the custodial sentence with restrictive rights.

Examples of these procedural impacts are the crimes of sponsoring improper hiring and disturbing of a public bidding process, which had their maximum penalty increased from two to three years. The increase ends up excluding them from the list of misdemeanors, making impossible, consequently, the benefits provided for in Law No. 9,099/95, such as non-prosecution agreements (NPAs) and deferred-prosecution agreements (DPAs).

Another increase in penalty that deserves attention is the crime of frustrating the competitiveness of a public bid, whose sentence became imprisonment from four to eight years – before it was detention of two to four years – which, in addition to raising the statute of limitations from eight to twelve years, also impacts the possibility of conditional suspension of the sentence, the replacement of custodial sentence by restrictive rights and the possibility of an initial open regime for the execution of the sentence.

The new law also provided for a new crime in Article 337-O consistent in a designer omitting relevant data or information, with a corresponding penalty of imprisonment from six months to three years. This crime is an attempt to also punish those in charge of defining specific conditions for the submission of proposals for public bids and contracts such as surveys, topography, environmental conditions, demand studies, among others. These are issues that, by their nature, directly influence the price and/or conditions of supply of the product or the provision of the services.

Finally, Article 337-P establishes new criteria to calculate the minimum fine in case of crimes against public bidding procedure and contracts. The old maximum of 5% of the value of the contract was waived in the imposition of penalty, provided that it is calculated based on the criteria of the Penal Code.

Law No. 8,666/93 provided that the amount raised by the criminal fine should be allocated to the public agency harmed by criminal conduct. The new law withdrew this provision, probably in an attempt to fix the punitive nature of the fine opposed to the indemnification aspect, which should be discussed in civil action.

The criminal amendments came into force on the date of publication of the law, while the provisions relating to the bidding process and the conclusion of administrative contracts will enter into force only in April 2023.

The effective implementation of criminal changes should still be the subject of deep jurisprudential discussions. The courts will face the difficult task of reconciling the criteria of criminal law enforcement in time with the dates of conclusion and expiration of public contracts in progress, in addition to establishing the parameters of compatibilization of the old public procurement guidelines with the new criminal provisions for the next two years.

Below is a comparative table of the criminal provisions.

| Law No. 8,666/93 | Law No. 14,133/21 |

|

Art. 89. To waive or to not require bidding outside the circumstances provided for by law, or to fail to observe the formalities pertaining to the dispensation or non-enforceability:

Penalty – detention of 3 (three) to 5 (five) years, and fine. Single paragraph. In the same penalty incurs the one who, having proven to have run for the consummation of illegality, benefited from the exemption or illegal unenforceability, to enter into a contract with the Public Power. |

Illegal direct contracting Penalty - imprisonment, from 4 (four) to 8 (eight) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 90. To frustrate or defraud

Penalty – detention, from 2 (two) to 4 (four) years, and fine. |

Frustration of the competitive bidding character Penalty - imprisonment, from 4 (four) years to eight (eight) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 91. To sponsor, directly or indirectly, private interest before the Administration, causing the establishment of bidding or the conclusion of a contract, the invalidation of which may be decreed by the Judiciary:

Penalty – detention, from 6 (six) months to 2 (two) years, and fine. |

Improper hiring sponsorship Penalty - imprisonment, from 6 (six) months to 3 (three) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 92. Admit, enable or give cause to any modification or advantage, including contractual extension, in favor of the adjudicatory, during the execution of contracts concluded with the Public Power, without authorization in law, at the convening act of the tender or in the respective contractual instruments, or, furthermore, pay invoice with deprecation of the chronological order of its presentation:

Penalty – detention, from 2 (two) to 4 (four) years, and fine. Sole paragraph. |

Irregular modification or payment in administrative contract Penalty - imprisonment, from 4 (four) years to eight (eight) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 93. To prevent, disturb or defraud the performance of any act of bidding procedure:

Penalty – detention, from 6 (six) months to 2 (two) years, and fine. |

Disturbance of bidding process Penalty - detention, from 6 (six) months to 3 (three) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 94. To breach the secrecy of a proposal presented in

Penalty – detention, from 2 (two) to 3 (three) years, and fine. |

Violation of confidentiality in bidding Penalty – detention, from 2 (two) years to 3 (three) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 95. To remove or seek to fend off bidders, through violence, serious threat, fraud or offering the advantage of any kind:

Penalty – detention, from 2 (two) to 4 (four) years, and fine, in addition to the penalty corresponding to violence. Single paragraph. Incurs the same penalty who abstains or gives up bidding, due to the advantage offered. |

Withdrawal of bidder Penalty- imprisonment, from 3 (three) years to 5 (five) years, and fine, in addition to the penalty corresponding to violence. Single paragraph. Incurs the same penalty who abstains or gives up bidding due to advantage offered. |

|

Art. 96. Fraud, to the detriment of the Public Treasury, bidding established for the acquisition or sale of goods or goods, or contract arising from it:

I – arbitrarily raising prices; Penalty – detention, from 3 (three) to 6 (six) years, and fine. |

Fraud in bid or contract I – delivery of goods or provision of services with quality or in quantity different from those provided for in the notice or in the contractual instruments; Penalty - imprisonment, from 4 (four) years to eight (eight) years, and fine. |

|

Art. 97. To admit to bidding

Penalty – detention, from 6 (six) months to 2 (two) years, and fine. Sole paragraph. It is the same penalty that, declared disreputable, will bid or contract with the Administration. |

Disreputable contracting Penalty – imprisonment, from one (1) year to 3 (three) years, and fine. § 1º To enter into a contract with a company or professional declared disreputable: Penalty – imprisonment, from 3 (three) years to 6 (six) years, and fine. § 2º It is the same penalty of the caput of this article that, declared disreputable, will participate in bidding and, in the same penalty of § 1 of this article, the one who, declared disreputable, will contract with the Public Administration. |

|

Art. 98. To prevent, avoid or unjustly hinder the registration of any interested party in the registration records or to improperly promote the alteration, suspension or cancellation of registration of the registrant:

Penalty – detention, from 6 (six) months to 2 (two) years, and fine. |

Undue impediment Penalty - imprisonment from 6 (six) months to 2 (two) years, and fine. |

|

|

Serious omission of data or information by designer Penalty – imprisonment, from 6 (six) months to 3 (three) years, and fine. § 1º It is considered a condition of contouring the information and surveys sufficient and necessary for the definition of the project solution and the respective prices by the bidder, including surveys, topography, demand studies, environmental conditions and other environmental elements impacting, considered minimum or mandatory requirements in technical standards that guide the elaboration of projects. § 2º If the crime is committed in order to obtain benefit, direct or indirect, own or other, applies twice the penalty provided for in the caput of this article. |

|

Art. 99. The penalty provided for in arts. 89 to 98 of this Law consists of the payment of an amount fixed in the judgment and calculated in percentage indices § 1° The indexes referred to in this article may not be less than 2% (two percent)

|

Art. 337-P. The penalty of a fine imposed on the crimes provided for in this Chapter shall follow the calculation methodology provided for in this Code and may not be less than 2% (two percent) of the value of the contract tendered or concluded with direct contracting. |

- Category: Environmental

Since the 1990s, the Environmental Company of the State of São Paulo (Cetesb) has been working to define the management procedures of contaminated areas. In 1999 and 2001, the environmental agency released the first and second versions, respectively, of the Contaminated Areas Management Manual.

The first manual was the result of the Technical Cooperation Project between Cetesb and GTZ, a German government agency, and had as its primary objective to define the methodology for identifying, managing, and rehabilitating contaminated areas.

The guidelines provided for in the manual drafted by Cetesb were not limited to the state of São Paulo. They influenced the enactment of environmental legislation on the subject, contributing to the creation of a robust legal framework throughout the country.

In the State of São Paulo, since 2009, State Law No. 13,577/09 has been in force, which is currently regulated by State Decree No. 59,263/13 and provides for guidelines and procedures for the protection of soil quality and the management of contaminated areas. The legal text is directly linked to the technical guidelines established by Cetesb in its manual.

Recently, in 2017, Cetesb issued Board Decision No. 038/2017/C, which establishes the current technical requirements on:

- the approval of the procedure for the protection of soil and groundwater quality;

- the procedure for the management of contaminated areas; and

- guidelines for the management of contaminated areas to be followed during environmental licensing proceedings.

To keep up with the progress of the legislation, as well as the technology involved in the subject, Cetesb updated the manual, having released its third version on April 8, 2021. An initiative of Cetesb's Environmental Board for the Management of Contaminated Areas, the manual was released in digital format and is available on the environmental agency’s website.

The new manual is the result of a joint effort by several stakeholders, such as representatives of the industrial sector, financial institutions, universities, and technical consultants that make up the Chamber. Multidisciplinarity contributes to the drafting of a robust document encompassing subjects related to the performance of the different agents involved in the management of contaminated areas.

The manual also refers to European and North American practices to guide procedures for investigating contaminated areas. For this reason, it is expected that the document will continue to be used as a reference in other states of Brazil, as was already the case with previous versions.

In the third edition, Cetesb’s foresees to publish 83 sections, distributed in 16 chapters. In April, some chapters were already released, which deal, among other aspects, with the history of management of contaminated areas in the state of São Paulo, the applicable methodology, the annotation of existence of contaminated areas in the property’s registry, the procedure for managing critical contaminated areas, the identification of areas with potential for contamination, and the survey of information for the preliminary evaluation, such as existing information and fieldwork. The remaining chapters will be published throughout the year, and their full release is expected to be completed by October 2021.

In addition to updating the information contained in the other versions, the new chapters will address current and relevant topics, such as (i) investigations and risk assessment of contaminated areas; (ii) the drafting and implementation of the intervention plan; (iii) monitoring for closure; (iv) the issuance of the Rehabilitation Term for Declared Use; and (v) instruments, including guiding values, the State Fund for the Prevention and Remediation of Contaminated Areas (Feprac) and environmental education.

At the launch event of the manual, Cetesb highlighted that the management procedures of contaminated areas should consider as reference the Board Decision No. 038/2017/C and the manual. In case of absence of information, the technical standards of the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT NBR) may be used, as long as it is applied according to the board's decision and the manual. If the board’s decision or the manual do not provide specific guidance, the Environmental Board for the Management of Contaminated Areas will decide the applicable procedures.

The disclosure of the updated manual evidence Cetesb's commitment to the subject, playing an essential role in standardizing the procedure for managing contaminated areas not only in the state of São Paulo, but throughout Brazil.

- Category: Tax

Despite the widespread crisis caused by the pandemic, the trajectory of accelerated and steady growth in agribusiness ensured that the fall in the Brazilian GDP was not so tragic. According to data released by the Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock of Brazil (CNA) and the Center for Advanced Studies in Applied Economics (Cepea), the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of agribusiness in 2020 grew a record 24.31% compared to 2019 figures.[1] An extraordinary advance, especially when considering the major obstacles in the taxation of the sector, such as reduction of tax benefits and the rules on PIS and COFINS credits. In the list of fiscal obstacles that impact on agribusiness one finds the Rural Territorial Tax (ITR), which is rarely addressed by legal scholarship on tax law and on which it is necessary to make some comments.

Despite its national scope, the ITR goes beyond the most relevant tax debates, such as discussions on tax reform proposals, quite possibly due to their reduced impact on federal revenue. According to the 2019 Annual Inspection Report, published by the Internal Revenue Service, the ITR accounted for less than 1% of all assessments from audits.

However, although it is not a significant tax in terms of revenue, the ITR is a tax of unquestionable relevance for the agribusiness sector, directly affecting the tax burden players in this market.

According to the original wording of Article 153 of the Federal Constitution, the ITR is a tax of the Federal Government. But since 2003, with the enactment of Constitutional Amendment No. 42, municipalities may choose to oversee and collect the federal tax by entering into an agreement.

For municipalities, the advantage of this division of powers is that proceeds from the collection of the tax on properties established in their territory will be 100% directed to the municipality, expanding local revenue. For the Federal Government, which would need to pass part of the collection on to the municipalities (article 158, II, of the Federal Constitution of 1988), the benefit is to ensure greater effectiveness in the supervision of the tax.

In a country with continental dimensions, delegating the activity of assessment and collection to the municipalities is a reasonable measure and, in a way, even desirable. However, there are issues arising from the dispersal of collection activities that merit debate and that require further reflection.

The first question is related to preservation of the uniformity of the general premises of the tax. Although the competence to legislate on assessment criteria remains exclusive to the Federal Government, municipalities end up interfering – in a questionable manner – in the composition of the tax calculation basis when they go through the assessment and collection activity.

As we know, the taxable event of the ITR is the ownership, possession, or useful domain of property located outside the urban area of the municipality, based on calculation of the assessment value of the unbuilt land (VTN).

The VTN, in turn, per the definition of Normative Instruction RFB No. 1,877/19, is the market price of the property, which is established considering the following criteria: (i) location of the property, (ii) agricultural aptitude, and (iii) size of the property.

By signing an agreement with the Federal Government to oversee the ITR, in exchange for the benefit of keeping the total amount of the tax collected, municipalities begin to have the task of periodically indicating the value of unbuilt land per hectare (VTN/ha) that will serve as a reference to update the Land Price System (SIPT) of the Internal Revenue Service. The SIPT is a database fed by the municipality that allows the taxpayer to consult the reference agenda of the VTN of the locality and is used in any levies to collect the tax.

As a reflection of this "municipalization of the tax", there is, in practice, a diversification of the criteria for measuring the value of the land, which, in turn, will directly affect the value of the ITR.

For example, the neighboring municipalities of Sarzedo and Ibirité, in Minas Gerais, whose VTNs are, respectively, R$ 375,659.78 and R$ 74,134.90 per hectare for cropland. In addition to the absurd discrepancy in value, the comparison with the NV in the municipality of Sorriso, Mato Grosso, makes more evident the lack of criteria in measuring the NMV. A soybean production center in Brazil and the Brazilian municipality with the highest value of agricultural production, Sorriso established a VTN of R$ 4,763.09 per hectare for cropland.

Although the SIPT was created to provide transparency and certainty regarding the VTNs calculated, in practice, a lot of table data does not meet the criteria required by the legislation.

Moreover, the transfer of collection capacity to municipalities increases the risk of inversion of the intent to merely raise the rural tax, impairing its typically extra-fiscal function. Article 153, VI, of the Federal Constitution of 1988 (current wording), regulated by Law No. 9,393/96, gives the tax a major extra-fiscal function, which must be guarded so that it always has a positive impact on the productive use of land.

With regard to administrative discussions on collection of the tax, because it is a tax within the competence of the Federal Government, cases involving the ITR are analyzed by the Administrative Tax Appeals Board (Carf), more specifically, by the panels of the 2nd Section.

In the Carf, the ITR is a tax that has seldom appeared in recent litigation – the use of the term ITR in the field "search decisions" on the Carf's website returns, for the most part, cases with taxable events prior to 2010. But precisely because of the municipalization and the increase in supervision, the ITR should gain more space on the agenda for discussions.

Last year, the 2nd Panel of the Upper Chamber of Tax Appeals (CSRF) reviewed various cases[2] discussing the need to present the Environmental Declaratory Act (ADA) to exclude the Permanent Preservation Area (APP) from the ITR calculation basis.

In such cases, the tax requirement was based on Article 17-O, head paragraph and paragraph 1 of Law No. 6,938/00, a rule that is still in force, which requires the ADA to reduce the rural tax. However, this obligation to submit the ADA fell with the case law established by the Superior Court of Appeals (STJ) – see REsp No. 587.429/AL – and the opinion issued by the Attorney General of the National Treasury PGFN/CRJ 1329/2016. Although neither the Decision by the STJ nor the opinion of the PGFN are formally binding on the Carf, the 2nd Panel of the CSRF, in a close vote, gave cause for gains for the taxpayer, deciding in favor of the need to preserve the coherence of the jurisprudential interpretation of the legal system and dispense with the requirement of the ADA in order to recognize the non-application of ITR in an environmental preservation area (provided that the evidence of the area is validated by means of a technical report prepared under the legislation).

The decision was also a breakthrough, but the other controversies regarding the ITR remain. It is expected that Carf, as the body responsible for reviewing tax assessments, will continue to give the most correct interpretation of the current normative provisions, maintaining the constitutional and legal contours of the tax, without restrictions or invasions.

In another year of the pandemic, a correct analysis of the ITR measurement criteria is necessary for agribusiness to continue advancing in Brazil.

[1] https://www.cnabrasil.org.br/boletins/pib-do-agronegocio-alcanca-participacao-de-26-6-no-pib-brasileiro-em-2020

[2] Among them, Ac. 9202-009.243 and 9202-009.343

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Mauro Bardawil Penteado, Pedro Henrique Jardim, André Camargo Galvão, Rafaela Tavares Ramos and Caio Colognesi.

Decree No. 10,672/21, published in the Official Gazette (DOU) on April 13, regulated Law No. 12,815/13 (Ports Law), creating a rite that allows the exemption from bidding for port lease, in addition to establishing procedures and conditions for the temporary use of areas and facilities located within the polygonal of the organized port. The following are the main changes introduced by the decree:

Exemption from bidding for the absence of multiple interested parties. The decree allows the exemption from bidding when it is proven the existence of a single interested in the exploration of port facility located within the organized port. The port authority shall make a public call within 30 days to identify the existence of other interested parties in the exploration of the area and the port facility, the extract of which will be published in the DOU, containing minimum information stipulated by the decree. Any potential interested party must formally express its interest through a document filed with the competent port authority.

The expression of interest presupposes the commitment of the interested party (who must be a legal entity) to (a) conclude the lease when he is the sole participant in the public call or (b) submit a valid tender in a bidding event, if there is more than one interested party.

The commitment will be signed by proving the provision of a proposal guarantee, as a way to avoid the expression of interest for delaying purposes.

Exemption from bidding for temporary use contracts. The decree allows the port administration to enter into a temporary contract for the use of port areas and facilities located within the polygon of the port organized with an interested party in the movement of cargo with unconsolidated market, that is, cargoes not regularly moved in the port in the last five years. Thus, the bidding process is exempted.

The temporary use of port areas and facilities will be structured through a Temporary Contract for the Use of Port Areas and Facilities, which will be signed between the interested party and the competent port administration. This contract must comply with the following specifications, among others: an non-extendable period of up to 48 months and use of the object area compatible with the development and zoning plan approved by the granting authority.

If there is more than one interested and no physical availability to allocate all interested parties simultaneously, the port administration will make simplified selection process to choose the project that best meets the public interest and the organized port.

Change in the rules of the port bidding procedure. The decree amends the minimum deadline for the submission of proposals, which was previously set to 100 days from the date of publication of the tender notice. Now, this period becomes the one stipulated by the notice, observing the legal minimum period. The decree also granted the National Waterway Transport Agency (Antaq) the competence to, within 120 days of the date of publication of the decree, fix the limit value of contracts in which it is not necessary to hold a public hearing for the bidding event. Thus, it will not be necessary to observe the fixed amount tied to Law No. 8,666/93 (Bidding Law), stipulated at R$ 330 million.

Simplified feasibility study. In addition to the hypotheses of exemption from bidding, Decree No. 8,033/13 established that previous studies of technical, economic and environmental feasibility of the purpose of the lease or concession could be carried out in a simplified manner, if they met the criteria set out in the regulation, one of which was the limit value of R$ 330 million. With the publication of Decree No. 10,672/21, this value limit criteria was withdrawn and maintained only the contractual term of up to 10 years.

Changes in the initial deadline for port concessions. The decree removed the limitation of time limit for the first contractual period of a port concession, previously determined in 35 years, but maintained the maximum limit of 70 years.

- Category: Succession planning

The majority of the Plenary of the Supreme Court (STF) established, in February, the theory that states and the Federal District cannot collect Transmission Tax on Donations and Inheritance (ITCMD) on donations and inheritances received from abroad before the Brazilian Congress regulates the issue through a complementary law.

The theory was established in the judgment of Extraordinary Appeal No. 851,108 (Topic 825), which occurred under the general repercussion arrangement {for reviewing appeals} and, therefore, with binding effect. Most Justices (7 x 4) concluded that states and the Federal District cannot institute collection by their own law.

According to the decision, the Federal Constitution provides that it is incumbent on federal supplementary law, and not to ordinary state laws, to regulate the matter and, to date, there has been no complementary law on the subject. Therefore, the states and the Federal District are prevented from requiring payment of ITCMD in these situations.

In the specific case, the Supreme Court reviewed an appeal brought by the State of São Paulo against a decision by the Court of Appeals of São Paulo (TJ-SP) that found article 4 of São Paulo State Law No. 10,705/00 to be unconstitutional. The provision provided that the state could charge the ITCMD on donations and inheritance from abroad received by people residing in the state.

Despite the favorable understanding of taxpayers, the majority of Supreme Court Justices (9 x 2) opted for the proposal to soften the effects of the decision. Thus, it will be valid for facts that occurred after publication of the judgment and for facts discussed in lawsuits not yet finalized at the time of publication of the judgment, which has not yet occurred and should be analyzed to confirm the position adopted by the court.

In summary:

| PRACTICAL EFFECTS OF THE DECISION AND SOFTENING OF THEM | |

| Taxable events prior to publication of the judgment | Taxable events after publication of the judgment |

| If there is state law instituting the collection, there is a risk of charging of ITCMD. | ITCMD may be charged only if there is a federal complementary law regulating the matter and state law instituting the tax. |

| Taxpayers who have already paid the ITCMD will not be able to recover the amounts paid. | |

| If the taxpayer already has a legal action in progress to discuss the issue, there should be no charge of ITCMD. | |

The decision is extremely relevant in the planning of assets and succession so that increasingly structures abroad are used to hold assets, as well as succession vehicles, such as trusts and foundations, whose beneficiaries are Brazilian. In addition, there are many Brazilians living abroad.