- Category: Tax

An old and even somewhat forgotten discussion has come to the fore again in recent years. It is the limitation on the taxable base for contributions intended for other entities and funds, commonly called third-party contributions, including Sesi, Senai, Sesc, Senac, Sebrae, Incra, Sescoop, Sest, Senat, and FNDE (education allowance).

The object of the discussion is the validity (or lack thereof) of article 4, sole paragraph, of Law No 6,950/81 - a provision that imposed a limitation on the taxable base for social security contributions and third-party contributions, stipulating that the contribution salary could not exceed the limit of 20 times the highest minimum wage in Brazil.

This is because article 3 of Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 prescribed that the "company's contribution to social security" would not be subject to "the limit of twenty times the minimum wage provided for by article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81."

Taxpayers argue that this decree revoked the application of the limit only for Social Security contributions (the employer's contribution of 20% on payroll) and not for third party contributions (intended for other entities and funds), mentioned in the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81.

Considering that article 3 of Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 prohibited application of the limitation only to the company's contribution to Social Security, the theory that the limitation continues to be applied to "quasi tax contributions" destined to other entities and funds is defended.

In our view, article 3 of Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 was not intended to revoke article 4. We explain: the rule did not simply repeal article 4 of Law No 6,950/1981, which could lead to the conclusion that the entire provision - including the single paragraph dealing with the limit on third-party contributions - was repealed.

Article 3 of Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 prescribed that the calculation of the contribution due to Social Security (defined in the head paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81) "is not subject to the limit of twenty times the minimum wage." In our opinion, with the promulgation of this article, the limit corresponding to 20 times the highest minimum wage in force in Brazil is no longer applicable to contributions due to Social Security (employer contributions).

We also believe that Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 did not prohibit application of the limit of 20 minimum wages for third party contributions, since it did not provide for the revocation of such limit, as provided for in the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81.

In other words, the limitation provided for in the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81 remained unchanged: the taxable base for contributions due to other entities and (quasi tax) funds linked to compliance with the limit of 20 minimum wages was maintained.

According to the General Theory of Law, a law is valid, in force, and effective until it is repealed or modified by another, which, as it seems to us, did not occur in the present case. Repeal by a subsequent law may occur in the following manners: (i) express revocation (by express declaration) or (ii) tacit revocation (when the new law is not compatible with the content of the old law dealing with the same matter or when it entirely regulates the matter dealt with in the prior law).

However, none of these situations seems to have occurred in relation to the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81, since: (i) there was no provision for temporary validity for the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81; (ii) no law was published that expressly repealed the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81; (iii) there has been no publication of a law incompatible with the determination contained in the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81; and (iv) there was no publication of a law fully regulating the matter disciplined by the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/81.

The Federal Government, for its part, has argued that the repeal of the limit for social security contributions was extended to the taxable base for social contributions for other entities and funds (third party contributions). According to the Federal Government, one could not be allowed to repeal only the head paragraph of article 4, keeping its sole paragraph isolated. For the Federal Government, the repeal of the head paragraph of article 4 would entail automatic repeal of its sole paragraph.

An analysis of the precedents on the matter shows that, within the Superior Court of Courts (STJ), the issue was reviewed in REsp No. 953.742 in 2008. The appeal was decided in favor of taxpayers by the 1st Panel of the STJ's 1st Section. After this judgment, it is also possible to find sole judge decisions handed down by STJ in the same direction favoring taxpayers in 2014, 2017, and 2019. In these decisions, the STJ seems to concur with the taxpayers' arguments, showing that it adheres to the understanding that Decree-Law No. 2,318/86 repealed only the limitation on social security contributions (employer's payroll contribution at the rate of 20%) and not on third-party contributions, mentioned in the sole paragraph of article 4 of Law No. 6,950/1981.

More recently, the First Panel of the STJ reaffirmed this understanding in the judgment of AgInt no REsp 1.570.980/SP, causing positive expectations among taxpayers, especially after the Federal Supreme Court (STF) decided, in the context of an appeal heard due to general repercussion, on the constitutionality of the contribution to INCRA, in accordance with Constitutional Amendment No. 33/01 - another issue related to the legitimacy of assessment of third-party contributions.

But even with the precedents handed down thus far by the STJ, which are mostly favorable to taxpayers, it is not yet possible to state that there is firm case law in their favor, either because of the small number of precedents or because there is no precedent derived from a judgment of a binding nature.

Sensitive to the need for unification of precedents, and also because of the considerable increase in cases involving the matter, the Superior Court of Appeals, on the eve of the judicial recess, bound Special Appeal No. 1,898,532[1] to the system for repetitive appeals (repetitive topic No. 1,079).

This means that the 1st Section of the STJ, the body that brings together the Justices of the 1st and 2nd panels and that deals with tax matters, will review the issue and, in a judgment that will be binding in nature, must definitively resolve the discussion.

In any event, in view of the not yet definitive scenario of the case law on the limitation imposed by article 4, sole paragraph, of Law No. 6,950/81 for determining the taxable base for third-party contributions and while Special Appeal No. 1.898.532 has not been ruled on, there is a high chance of questioning by the tax authorities if the taxpayer, on its own account and without the support of judicial authorization, calculates such contributions based on said limit and/or appropriates credits in connection with any past indebtedness.

The adoption of a more conservative stance - the filing of a lawsuit, for example - deserves to be evaluated, especially considering that the precedents handed down thus far by the STJ seem to be favorable to taxpayers.

In our opinion, this may be relevant to any decision by the bodies of the Judiciary to grant provisional judicial authorization to the taxpayer (via emergency relief or preliminary injunctive relief in an application for mandamus) to ascertain and collect the contributions of third parties based on the application of the limit of the taxable base to the value of 20 minimum wages.

The filing of a lawsuit would also allow interruption of the statute of limitations, such that, at the end of the lawsuit and in the event of success, the taxpayer could achieve recognition of the right to offset/refund of the undue payment made as of the fifth year prior to the filing date.

[1] Civil procedure. Special appeal. Code of civil procedure of 2015. Applicability. Proposal of binding effect as representative of the controversy. Tax. "Quasi tax contributions." Taxable base. Ascertainment. Application of the ceiling of twenty (20) minimum wages. Law No. 6,950/1981 and Decree-Law No. 2,318/1986.1. Delimitation of the question of law at issue: to define whether the limit of twenty (20) minimum wages is applicable to the taxable base of "quasi tax contributions collected on behalf of third parties," in accordance with article 4 of Law No. 6,950/1981, as its text was amended by articles 1 and 3 of Decree-Law No. 2,318/1986. 2. Special appeal submitted to the repetitive appeals system, in joint assignment with REsp n. 1.905.870/PR. (ProAfR no REsp 1898532/CE, opinion drafted by Justice Regina Helena Costa, first section, decided on December 15, 2020, DJe December 18, 2020).

- Category: Litigation

Law No. 11211/20, signed on December 24, introduced various changes in the Bankruptcy and Judicial Reorganization Law (Law No. 11,101/05 or the LRF). Among the main ones are those related to the role of the judicial trustee, whose main functions are to assist the court, caring for the good progress of the case, and to supervise the debtor's acts and compliance with the judicial reorganization plan.

The duties of the judicial trustee were expanded, notably due to the other innovations of the LRF, such as the possibility for creditors to present an alternative judicial reorganization plan, the express provision for the use of conciliation and mediation mechanisms, and the regulation of transnational bankruptcy.

The judicial trustee's duties may be divided among those (i) common to judicial reorganization and bankruptcy; (ii) exclusive to judicial reorganization; and (iii) exclusive to bankruptcy.

With regard to the common attributions, the LRF charged the judicial trustee with stimulating alternative methods of dispute resolution, such as conciliation and mediation. Although this provision is a novelty in the LRF, in practice, based on the Mediation Law, Resolution No. 125/2010 of the Judicial Review Board (CNJ) and an ordinance issued by state courts, mediation has long been applied in various cases of judicial reorganization, such as those of Oi and Saraiva, for which mediation was used to resolve various conflicts during the proceeding regarding the reorganization plan, debt claims, and bilateral disputes.

In addition, keeping in line with the digital era, it is now up to the judicial trustee, per provision of law, to maintain an electronic address on the Internet, through which updated information on the proceedings should be made available and requests for qualification and divergences of debt claims should be sent, which facilitates the monitoring of the judicial reorganization by creditors.

In the scope of the judicial reorganization, the judicial trustee also had the scope of its functions extended, mainly in relation to:

- inspecting the veracity and conformity of the information provided by the debtor to prepare the monthly activity report, the negotiations between debtors and creditors (ensuring that the parties not adopt dilatory or prejudicial arrangements) and the decisions of the general meetings passed by means of a consent form, electronic voting, or some other suitable mechanism (article 39, paragraph 5);

- submitting for a vote, in a general meeting of creditors rejecting the judicial reorganization plan proposed by the debtor, the granting of a 30-day period for the creditors to present their judicial reorganization plan (article 56, paragraph 4);

- submitting within 48 hours a report of the creditors' responses regarding the holding of a general meeting to resolve on the sale of assets, therein requesting the convening thereof.

The new powers of the judicial trustee in bankruptcy include:

- presenting, within 60 days of their investiture, a detailed plan for realization of the assets;

- selling all the assets of the bankrupt estate within a maximum period of 180 days, counted from the date of the filing of the notice of collection, under penalty of dismissal, except for reasoned impossibility, recognized by a judicial decision;

- in the event of insufficiency of the assets for the costs of the proceedings, promote sale of the assets collected within a maximum period of 30 days (for personal property) and 60 days (for real property), if the creditors do not request continuation of the bankruptcy; and

- collecting the amounts of deposits made in administrative or judicial proceedings in which the bankrupt is a party and which arise from attachments, freezes, seizures, auctions, judicial sales, and other cases of judicial constriction, with the exception of deposits of federal taxes.

One of the LRF's greatest innovations is the regulation of transnational bankruptcy proceedings, in which the performance of the judicial trustee is very relevant. It has authorization to appear in foreign judicial proceedings in the capacity of representative of the Brazilian judicial proceedings, in the event of bankruptcy, and obligation to cooperate and communicate with the foreign authority and with the foreign representatives.

The purpose of the changes in the judicial trustee's duties is to increase the participation of the court clerk’s office and allow it to act in a timely manner, which will end up increasing its responsibilities and its work. Although the novelties are beneficial to the system as a whole, because they increase legal certainty and speed up bankruptcy proceedings, they may discourage those interested in filling this position, especially because of the obligation to confirm the veracity of the debtor company's information.

In any event, it is expected that the actions of the judicial trustees will be under greater scrutiny, and it is up to the Judiciary, the creditors, the debtor, and the company as a whole to demand smoothness, speed, and commitment from the clerks of course in the performance of their duties.

- Category: Labor and employment

Algorithms are sequences of actions to be performed by software to solve a problem or achieve a certain result. They are used, for example, to automatically search for previously defined profiles in extensive databases in order to obtain specific data for a search, application, replacement of vacancy, and even diagnosis of diseases.

For the data to be obtained by the algorithm, it is essential to have a person responsible for defining the structure of the basis on which the data will be stored and a person responsible for supplying it, even based on virtual sensors, considering the parameters previously established. Human participation necessarily occurs at some of these moments, either to define the guidelines applicable to the algorithm or organize, develop, and govern the information.

There are various examples of the use of algorithms in labor relations, such as automatic review of job applicants' resumes or monitoring of employees' activities according to productivity targets set by the company for the purposes of bonuses or dismissal.

The question, however, is whether the use of algorithms alone is incompatible with Law No. 13,709/18, the General Data Protection Law (LGPD), which provides for the processing of personal data, including in digital media, by individuals or legal entities, in order to safeguard the privacy of data holders.

Before assessing any compliance situation, it is necessary to identify whether personal, sensitive, or anonymous data are involved, and whether these data are based on the LGPD for their processing.

Personal data may only be used in the following cases: fulfillment of a legal obligation, performance of studies by a research organization, performance of a contract or preliminary procedures related to the contract to which the data subject is a party, regular exercise of rights, legitimate interest, protection of credit, processing and shared use of data necessary for the execution of public policies, protection of life, protection of health, and by consent.

Sensitive data, on the other hand, cannot be used in the following cases: performance of a contract and protection of credit (if there is no consent from the data subject) and legitimate interest, but only in the other cases or to ensure prevention of fraud and security of the data subject in the processes of identification and authentication of registration in electronic systems.

If the data processed by the algorithm is anonymized and therefore cannot be identified, it will not be considered personal or sensitive and may be used. Considering that most algorithms process anonymized data, it is commonly understood that they do not have any prohibition on processing in the legislation, but this view is largely mistaken.

Anonymized data does not prevent certain processing of data from being considered discriminatory, which is prohibited by articles 3, subsection IV, and 5, subsection XLI, of the Federal Constitution and 6, subsection IX, of the LGPD. It must be kept in mind that algorithms, even if anonymous, are not impartial and may reflect prejudices rooted in the history of the data, as demonstrated by various recently reported cases that should be reviewed by companies.

The problem of algorithmic discrimination through the use of biased databases can still originate in data collection, including with human participation, and this situation has become increasingly common. For this reason, the Labor Prosecutor's Office has recently set up a group against algorithmic discrimination in order to investigate companies that use biased algorithms. It is called machine bias or algorithm bias.

The removal of biased algorithms is an issue that has been widely discussed by companies, which should review governance and human participation in the use of technology to legitimize it.

Facebook recently announced the launch of a board of experts from around the world with multidisciplinary and multicultural background, called Oversight Board Administration. This board is currently composed of 20 members and will be responsible for defining, for example, what type of content should or should not be removed from the social network, according to what is considered inappropriate, irrelevant, or excessive. It is an independent body that seeks to enhance the integration between the human being and artificial intelligence.

Another problem identified in the algorithms that process seemingly anonymized data refers to the decisions arising from their use. According to article 20 of the LGPD: “The data owner has the right to request review of decisions made solely on the basis of automated processing of personal data affecting his interests, including decisions to create his personal, professional, consumer, and credit profile or aspects of his personality.”

This means that if a certain algorithm has led to discriminatory treatment of the employee, both for recruitment and dismissal purposes, for example, the company must respect the principle of transparency, provided for in article 6, VI of the LGPD, and provide all necessary information on the processing of the data on which the decision was based, under penalty of being audited by the National Data Protection Authority (ANPD).

To confirm the legality of the algorithms, therefore, two questions must be taken into consideration and analyzed with great caution: classification of the data indicated (whether personal, sensitive, or anonymous) and whether they are legitimately presented in this manner.

Otherwise, the companies will be in breach of the LGPD and must review the use of the technology in accordance with the guidelines of the new regulation, under penalty of being subject to the administrative sanctions provided for by law (the application of which may occur as of August 1, 2021), as well as the payment of compensation for moral damages in the event of litigation in the labor sphere.

- Category: Restructuring and insolvency

Law No. 14,122, published on December 24 in the Official Gazette, updates the legislation on in-court reorganizations, out-of-court reorganizations, and bankruptcy of entrepreneurs and business companies. The text derives from Bill 4,458/20, which was approved by the Senate on November 25 and suffered some vetos by the President of Brazil.

To reflect the wording of the new law, we update below the table published on December 8 with the main points of change in the institutes of the current reorganization and bankruptcy legislation.

Analysis of the main changes |

|

|

Law No. 11,101/05 before Law No. 14,112/20 |

Law No. 11,101/05 after Law No. 14,112/20 |

|

Stay period · After the petition for judicial reorganization is granted, the stay period begins, an interval of 180 days for suspension of executions and acts of constriction against the debtor by creditors subject to the proceeding, which is intended to give breath to the negotiation of the judicial reorganization plan. · This period would be non-extendable under the LRF, but case law has admitted extension, occasionally even more than once, when the vote on the plan does not take place within 180 days for acts not attributable to the debtor. For reference, votes on plans for reorganizations in progress in the State of São Paulo have taken an average of 517 days, according to data from the 2nd Phase of the Bankruptcy Observatory of NEPI-PUC/SP and ABJ. · Bankruptcy-exempt creditors and the tax authorities are not affected by the stay period a priori. However, constrictions and foreclosures of essential capital goods are prohibited in such a period. According to the Superior Court of Appeals (STJ), the competent court to decide on the matter is that of the judicial reorganization. · There is no legal provision for a stay period in relation to mediation or out-of-court reorganization. |

Stay period · It expressly provides for the possibility of extending the stay of 180 days, for an equal period and a single time, provided that the failure to vote on the plan is not attributed to the debtor in possession. · The stay period may be extended a second time if creditors submit an alternative judicial reorganization plan, in the cases provided for in article 6, paragraph 4-A, and article 56, paragraph 4. (article 6, paragraph 4 and 4-A) · The stay period will continue to start from the granting of the processing of the case, but in the event of urgency, in limine relief may be granted for its effects to begin, in whole or in part, as of the filing of the case. · The rule regarding the possibility of execution and constriction by the tax authorities and bankruptcy-exempt creditors will continue. There will be an express legal definition of the jurisdiction of the court overseeing the reorganization to deal with the issue of essential capital goods in article 6, paragraphs 7 and 7-A. · There will be a legal provision for a stay period in the prior mediation and extrajudicial reorganization (for more details, see item on the subject, below). |

|

Prevention of the court · The rule of jurisdiction of the court by prevention did not cover requests for approval of out-of-court reorganization plans previously filed, although case law already recognized this possibility on the basis of an expansive interpretation of the rule. |

Prevention of the court · The assignment a petition for an out-of-court reorganization plan will also result in preventive jurisdiction of the court for any other bankruptcy, judicial reorganization, or out-of-court reorganization petition concerning the same debtor (article 2, paragraph 8). |

|

Arbitration agreement · The LRF is silent on this point, but case law already required companies in crisis to respect arbitration agreements. |

Arbitration agreement · The need to respect the arbitration agreement by the debtor in possession or bankrupt party, represented by the judicial trustee, will be established in positive law (article 6, paragraph 9). |

|

Distribution of profits or dividends · The LRF does not have provisions on the subject. |

Distribution of profits or dividends · Until the approval of the judicial reorganization plan, the debtor will be prohibited from distributing profits or dividends to partners and shareholders (article 6-A) |

|

Verification and registration of claims · Such provisions are listed in articles 7 to 20 of the LRF, and there are no express previsions regarding what happens with the registrations and objections in course, in the event of closure of the judicial reorganization. |

Verification and registration of claims · There will be an express rule as to the possibility of closing the judicial reorganization even if the General Table of Creditors has not been approved. With this, late registrations and objections will be reassigned to the judicial reorganization court as autonomous actions through the common procedure, and late registrations will have the competent credit reserve (article 10, paragraphs 7 to 9). · There will be specific treatment for registration of tax debts in the bankruptcy (article 7-A). · In the event of bankruptcy, there will be a three-year lapse period, counted from the decree of bankruptcy, for registrations and requests for a credit reserve (article 10, paragraph 10). · Apportionment in bankruptcy may occur even if the General Table of Creditors is not formed, provided that the class of creditors to be satisfied has already had all the judicial objections filed within the term provided for in article 8, except for the reserve of the disputed credits due to the delayed registration of credits distributed until then and not yet judged (article 16). |

|

Assignment of credits · Practice possible, but not regulated in the LRF. In bankruptcy, the assignment of labor debts denatures their characteristics, and the claim becomes unsecured. |

Assignment of credits · Promise of assignment or assignment must be immediately reported to the court overseeing the reorganization (article 39, paragraph 7). · In bankruptcy, any assignment of a credit will maintain the classification and characteristics of the credit (article 83, paragraph 5). |

|

Conciliation and mediation

· The LRF does not govern the practice of conciliation and mediation prior or incidental to a judicial reorganization proceeding. In practice, mediation has already been adopted in some judicial reorganizations, especially with a view to speeding up the procedures related to ancillary proceedings for verification of credits and to defining the means of reorganization and payment conditions to be arranged in the judicial reorganization plan. |

Conciliation and mediation

· Conciliation and mediation should be encouraged before and during judicial reorganization, at any level of appeal (article 20-A). · It will be possible to obtain urgent relief for the suspension of executions against the debtor for a period of up to 60 days prior to the filing of the judicial reorganization, for an attempt to reach a settlement with its creditors in a mediation or conciliation proceeding already instituted before the Judicial Center for Settlement of Conflicts and Citizenship. In the event of a subsequent request for judicial or extrajudicial reorganization, the time limit will be deducted from the stay period provided for in article 6 of the LRF (article 20-B, paragraphs 1 and 3). · Conciliation and mediation on the legal nature and classification of credits, as well as on voting criteria at the General Meeting of Creditors (GMC) will be prohibited (article 20-B, paragraph 2). · Settlements reached through conciliation or mediation must be approved by the competent court (article 20-C). · If judicial or extrajudicial reorganization is requested within 360 days as of the settlement signed in the conciliation or pre-trial mediation, the rights and guarantees of the creditors will be reconstituted on the terms originally contracted, with the exception of acts validly performed within the scope of the proceeding (article 20-C, sole paragraph). |

|

Role of the judicial trustee · Although it is currently common practice, there is no legal provision obliging judicial trustees to maintain a website with information on the proceedings in which they serve. · The judicial trustee is not obliged to certify the veracity of the information provided by the debtor, nor to supervise the negotiations held between debtors and creditors. · There is no provision for alternative methods of deliberations by creditors (e.g., by means of an consent form or electronic voting) and, therefore, there is no legal obligation for the judicial trustee to supervise such acts. · Obligation to sell the assets of the bankrupt estate has no time limit. The judicial trustee will request that the judge sell in advance perishable goods, which are deteriorable or subject to considerable devaluation or to risky or costly conservation. In addition, there is no express obligation for the judicial trustee to collect in bankruptcy the amounts of deposits in proceedings to which the bankrupt is a party, although it is currently understood that this is an implicit obligation. · There is no provision for cooperation mechanisms for transnational bankruptcy proceedings. |

Role of the judicial trustee · The judicial trustee will encourage mediation, conciliation, and other alternative methods of dispute resolution. · The judicial trustee will maintain an e-mail address with updated information on bankruptcy and judicial reorganization proceedings, with the main filings in the proceedings and monthly activity reports, and on the judicial reorganization plan, as well as for receipt of registrations and disagreements in the administrative sphere, unless a court decision to the contrary is entered. · The scope of the judicial trustee's duties under the judicial reorganization process will be broadened, notably (i) to inspect the veracity and conformity of the information provided by the debtor for purposes of preparing the monthly activity report; (ii) to inspect the negotiations between debtors and creditors, ensuring that the parties do not adopt dilatory or prejudicial arrangements; (iii) to inspect, by means of issuance of an opinion regarding their good standing, the decisions of the GMC by means of a consent form, electronic voting, or some other suitable mechanism (article 39, paragraph 5); (iv) to submit for a vote at the GMC that rejects the judicial reorganization plan proposed by the debtor the granting of a 30-day period for presentation of the judicial reorganization plan by the creditors (article 56, paragraph 4); (v) to submit within 48 hours a report of the creditors' responses regarding the holding of a General Meeting to resolve on the sale of assets, requesting its call. · The scope of the judicial trustee's duties within the scope of the bankruptcy proceedings will be broadened, namely: (i) the obligation to submit within 60 days of its appointment a detailed plan for realization of the assets; (ii) proceed with sale of all assets of the bankrupt estate within a maximum period of 180 days, as of the date of the filing of the notice of filing of the notice of collection, under penalty of dismissal, except for justified impossibility, recognized by a court decision; (iii) in the event of insufficiency of the assets for the expenses of the proceedings, procure sale of the attached assets within a maximum period of 30 days, for personal property, and 60 days, for real property, if the creditors do not request continuation of the bankruptcy; (iv) to collect the amounts of the deposits made in administrative or judicial proceedings in which the bankrupt appears as a party, arising from attachments, freezes, seizures, auctions, judicial sales, and other events of judicial constriction, with the exception of the deposits of federal taxes. · There will be provision for actions in the scope of transnational bankruptcy proceedings, notably (i) authorization to appear in foreign judicial proceedings in the capacity of representative of the Brazilian judicial proceedings, in the event of bankruptcy; and (ii) obligation of cooperation and communication with the foreign authority and with the foreign representatives. |

|

GMC · In person is the rule provided for in the LRF, but because of the covid-19 pandemic, virtual GMCs were admitted by the case law, including with the issuance of Recommendation No. 63 by the National Judicial Review Board (CNJ) in this regard. |

GMC · It may be virtual and may also be replaced, with the same effect, by a consent signed by creditors who meet the specific approval quorum or other mechanism deemed sufficiently secure by the judge (article 39, paragraph 4). · In addition to the duties provided for in the LRF, it may resolve on the approval of disposal of assets or rights of the debtor's non-current assets, not provided for in the judicial reorganization plan (article 35, item g). |

|

Abusive vote · There is no specific provision in the LRF, but there are decisions in which so-called abusive votes from significant creditors were disregarded whose contrary votes would prevent the achievement of the plan's quorum for approval. |

Abusive vote · Legal provision that the vote will be exercised by the creditor in the interest and in accordance with its judgment of advisability and declared null and void for abusiveness only when manifestly exercised to obtain an illicit advantage for itself or others (article 39, paragraph 6). |

|

Judicial reorganization of a rural producer · The LRF does not regulate the possibility for individual rural producers to request judicial reorganization. There is a divergence in the case law regarding whether the registration of rural producers is a declaratory or constitutive in nature and, therefore, whether the period of activity prior to registration must be taken into account in order to fulfill the requirement of at least two years of activity provided for in the head paragraph of article 48 of the LRF and whether or not the debts taken on prior to registration are subject to the judicial reorganization. |

Judicial reorganization of a rural producer · It will be defined that rural producers acting as individuals will be able to request judicial reorganization. · The special plan for rural producers may not involve debts of more than R$ 4.8 million (article 70-A). · Proof of the two-year period of activity established in the head paragraph of article 48 will be admitted through the Tax Accounting Book (ECF), or legal obligation to keep accounting records that may replace it (in the case of rural activity exercised by a legal entity), the Rural Producer Digital Cash Book (LCDPR), or legal obligation of accounting records that may replace it, the Income Tax Return, and balance sheet (in the case of rural activity exercised by an individual) (article 48, paragraphs 2 and 3). · Only credits arising exclusively from rural activities, even if not past due, will be subject to judicial reorganization (article 49, paragraph 6). · Appeals controlled and covered under articles 14 and 21 of Law No. 4,829/65 (article 49, paragraph 7) will not be subject to the effects of judicial reorganization. However, if they have not been renegotiated before the application for judicial reorganization, in the form of an act of the Executive, such credits will be subject to the effects of the plan (article 49, paragraph 8). · Credits relating to debts incurred in the last three years prior the request for judicial reorganization, as well as the respective guarantees, will not be subject to judicial reorganization (article 49, paragraph 9). |

|

Means of judicial reorganization

· The conversion of debt into capital (only the increase in share capital) is not expressly provided for, but is a means of reorganization used. · There is no provision for full sale of the debtor. |

Means of judicial reorganization · The conversion of debt into capital will now be included in the list of article 50 of the LRF and there will be no risk of succession or liability for debts to third parties. · The same rule of absence of liability and succession will be express for officers and directors who replace former officers and directors as a means of reorganization and for creditors who make contributions of funds (article 50, paragraph 3). · The creditors' alternative plan may also provide for the capitalization of credits, including foreign exchange of control, allowing the debtor's partner the right to withdraw (article 56, paragraph 7). · Full sale of the debtor: it will become a means of reorganization provided for in the list of article 50 of the LRF and can be used when the situation of the creditors who are not subject to the proceedings and who are not members is at least the same as it would be in a bankruptcy. In this scenario, the rule of absence of succession of the isolated productive unit (UPI) will be applied. |

|

Prior finding

· There is no legal provision for prior finding. · In practice, some judges order the holding of a prior finding before the granting of judicial reorganization, in line with Recommendation No. 57 of the National Judicial Review Board (CNJ). |

Prior finding · The prior finding will be provided for in the LRF, allowing the judge to carry it out when he deems it necessary (article 51-A). · The expert appointed by the judge will have no more than five days to submit a report issuing findings on the actual operating conditions of the debtor and the good order of the documentation submitted with the complaint (article 51-A, paragraph 2). · Dismissal of the processing of the judicial reorganization based on an analysis of the debtor's economic feasibility will be prohibited (article 51-A, paragraph 5). · If the preliminary finding detects strong evidence of fraudulent use of the judicial reorganization, the judge may reject the application, without prejudice to the issuance of an official letter to the Public Prosecutor's Office to take any criminal action that may be appropriate (article 51-A, paragraph 6). · If the prior finding shows that the debtor's principal place of business is not within the court's jurisdiction, the judge should order the case to be referred urgently to the competent court (article 51-A, paragraph 7). |

|

Alternative plan proposed by the creditors · There is no provision in this regard. Only the debtor may propose a plan for judicial reorganization, and any proposal for change made by creditors must have the debtor's express agreement. Rejection of the plan without meeting the requirements for a cram down entails conversion of the judicial reorganization into bankruptcy. |

Alternative plan proposed by the creditors · Creditors may submit an alternative plan if the debtor, after the extension of the stay period, is unable to put a plan to a vote or if, after the rejection of the plan at the GMC, the creditors vote for the granting of a 30-day period to do so, in which case the alternative plan must be voted on within 90 days of the GMC that decided on the submission of the plan. · The alternative plan should have a specific quorum of support from creditors representing, alternatively, more than 25% of the total credits subject to judicial reorganization or more than 35% of the credits of the creditors present at the GMC that decided to submit an alternative plan (article 56, paragraph 6, III); there may be no new obligations not provided for by law or in prior agreements with the debtor's partners; there will be a provision for exemption from personal guarantees provided by individuals with respect to credits held by creditors who supported/voted in favor of the alternative plan, which may not impose greater sacrifice on the debtor and its partners than that which would result from liquidation in bankruptcy (article 56, paragraphs 4 to 9). · The plan proposed by the creditors may provide for the capitalization of the credits, including the consequent change in the control of the debtor, allowing the exercise of the right of withdrawal by the debtor's partner (article 56, paragraph 7). · The alternative plan will only apply to judicial reorganizations filed after the entry into force of Law No. 14,112/20. |

|

Labor credits · They must be discharged within up to one year, and five minimum wages per employee of the strictly wage credits due in the three months preceding the claim must be paid within 30 days. |

Labor credits · The five minimum wages rule mentioned above will be maintained and the remainder may be paid within up to two years, provided that the plan, at the discretion of the judge: (i) provides sufficient guarantees; (ii) has been approved in class I; and (iii) guarantees payment of all labor credits (article 54, paragraphs 1 and 2). |

|

Sale of assets · UPI: there is no legal definition of what is an isolated productive unit (UPI). The no-succession rule exemplifies only tax and labor obligations and, following the example of IA 2237160-80.2019.8.26.0000 of the TJSP, most of the judgments hold that the sale must be made by some form of competition per article 142 of LRF to guarantee the absence of succession (there is, however, already a precedent of the STJ allowing another type of sale of a UPI within a judicial reorganization, provided it is authorized by a special quorum and indicating that the rule of absence of succession should prevail: REsp 1.689.187-RJ). · Assets: if there is no provision in the plan, the sale and encumbrance of assets require the judge's authorization, after hearing the creditors' committee (if any), and the judge must analyze the evident usefulness of the transaction. · Rule of succession: the general rules of succession of the acquirer in the sale of assets apply in reorganization proceedings not carried out in the form of a UPI. · Means of competition: auction, tender, and closed bid. · Price: Discussions regarding inadequate price are not uncommon. · Summons: summons of the Public Prosecutor's Office is mandatory. · Third party in good faith: no express provision in the LRF protecting their interests. |

Sale of assets · UPI: there will be legal definition (goods, rights and assets, tangible or intangible, such as corporate interest), the examples of absence of succession will continue to cite only the tax and labor ones, and the obligation to follow one of the competition modalities of article 142 of the LRF will continue (articles 60 and 60-A). · Assets: if there is no provision in the plan, sale and encumbrance of non-current assets (this is the novelty) will require the authorization of the judge, after hearing the creditors' committee, if any (the requirement of evident utility will cease to exist). Creditors with a joint claim in excess of 15% of the total amount of the liabilities, if they provide a bond and provided that they present justified reasons, may request a GMC to resolve on the matter, and the judicial trustee will explain the matter to the judge, convening a GMC, if the requirements are met. All this should be done quickly, in accordance with the legal deadlines and in the least costly manner, with the objecting creditors bearing the associated costs. · Rule of succession: all forms of divestiture made in accordance with the law shall be considered judicial sale for all purposes and effects. · Means of competition: article 142 of the LRF will provide for an electronic auction, a competitive process organized by a specialized agent of unblemished reputation and any other modality approved under the law. · Price: there can no longer be any discussion of a negligible or inadequate price. A third party contesting the sale must make or present a firm offer from a third party and a guarantee 10% of the value of the offer. Raising an undue objection on any point will be an act that undermines the dignity of justice. · Summons: a summons of the Public Prosecutor's Office and the tax authorities will be mandatory. · Third party in good faith: the sale of assets or guarantee granted by the debtor to a bona fide purchaser or lender, provided that it is carried out by express judicial authorization or provided for in an approved judicial or extrajudicial reorganization plan, may not be annulled or rendered ineffective after the consummation of the legal transaction with the receipt of the corresponding funds by the debtor. |

|

Partner or supporting creditor · Doctrinal and jurisprudential creation based on the spirit of article 67 of the LRF, which allows, based on the provisions in the plan and with justifications, that a certain creditor, named partner, or supporter, has privileged treatment in judicial reorganization in relation to other creditors of the same class. |

Partner or supporting creditor · Article 67, sole paragraph, will permit differentiated treatment of credits subject to judicial reorganization for suppliers of goods or services that continue to provide them normally after the application for judicial reorganization, provided that such goods or services are necessary for the maintenance of the activities and that the differentiated treatment is appropriate and reasonable as regards the future business relationship. |

|

DIP financing · The treatment provided for in article 67 of the LRF is insufficient and does not provide the necessary super priority. Thus, the vast majority of cases of financing that have existed in Brazil have always relied on guarantees, especially those of a fiduciary nature, and contractual arrangements for obtaining super-priority. · There is also no express provision in the LRF protecting third parties in good faith. · There is no provision in the LRF authorizing the creation of a subordinated guarantee on assets of the debtor without the consent of the holder of the original guarantee. · Experience shows that DIP financing cases ended up involving much litigation. |

DIP financing · Superpriority will be provided for by law (article 84). · Article 69-B will provide that a change in the level of appeal against the decision authorizing the engagement may not alter the bankruptcy-exempt nature or the guarantees given by the debtor to the lender in good faith, if disbursement has been made. · Article 69-C will authorize the establishment of a subordinated guarantee on one or more of the debtor's assets in favor of the lender of a debtor under judicial reorganization, waiving the consent of the holder of the original guarantee, with the proviso that the subordinated guarantee, in any event, will be limited to any excess resulting from the disposal of the asset subject to the original guarantee and that such provision will not apply to any type of fiduciary sale or fiduciary assignment. · Article 69-E will provide that financing may be provided by any person, including family members, partners, and members of the debtor’s group. · Article 69-D will provide that, in the event of conversation of the reorganization into bankruptcy, the financing agreement will be considered automatically terminated and the guarantees provided and preferences will be preserved up to the limit of the amounts actually delivered to the debtor before the date of the judgment that converted the judicial reorganization into bankruptcy. |

|

Procedural and substantive consolidation · Not regulated in the LRF. · Procedural consolidation is allowed on the basis of the rules for joint litigation in the Code of Civil Procedure (CPC), which apply where not incompatible with bankruptcy procedure, pursuant to article 189 of the LRF. · Substantive consolidation has divergent case law regarding the requirements, the competence of the decision on the subject, criteria, and quorums applicable to voting. |

Procedural and substantive consolidation · The LRF will have a provision stipulating the competent court, the requirements, the necessary documentation, and the form of voting in case of procedural consolidation (article 69-G). · The decision on the substantial consolidation may, exceptionally, be made by the judge and the requirements for its acceptance will be the finding of interconnection and confusion between assets or liabilities of debtors belonging to the same economic group, such that it is not possible to identify their ownership without excessive expenditure of time or resources, through the finding of at least two of the following events (i) existence of cross guarantees; (ii) relationship of control or dependency; (iii) identity of the corporate structure; and (iv) joint action in the market, which has generated criticism of the bill (article 69-J). · In case of substantive consolidation, there will be immediate extinguishment of fiduciary guarantees and credits held by one debtor against the other (article 69-K). · There will be a rule providing that secured guarantees will not be prejudiced in substantive consolidation, except with the approval of the holder (article 69-K). |

|

Possibility for the tax authorities to file for bankruptcy of the debtor · Although article 97, IV, of the LRF provide that any creditor may file for bankruptcy of the entrepreneur and of the business company, the currently settled understanding of the STJ is to the effect that the Public Treasury does not have standing to file for bankruptcy for companies and/or businessmen. · However, in an extended judgment held in August of 2020, the 1st Chamber of Business Law of the Court of Appeals of the State of São Paulo (TJSP), by majority vote, upheld the appeal so as to (i) annul the decision that had rejected the complaint and extinguished the proceeding without a resolution of the merits, on the grounds that the National Treasury had no procedural interest; and (ii) order the regular continuation of the petition for bankruptcy filed by the Federal Government, represented by the Attorney’s Office for the Federal Revenue Service, against a company engaged in the trade and distribution of food products. · The TJSP emphasized that, in the case at hand, the petition for bankruptcy was not based on article 94, subsection I of the LRF (whose more restrictive understanding should prevail) but on article 94, subsection II, since the Federal Revenue Service, although it filed for a tax foreclosure, has not located sufficient assets of the debtor to satisfy the debt. Having exhausted the means to satisfy its claim, it would not be possible to withdraw from the public body the possibility of filing for bankruptcy of the debtor. |

Possibility for the tax authorities to file for bankruptcy of the debtor · The tax authorities may petition for judicial reorganization of the debtor in bankruptcy if (i) there is nonperformance of the installment payments of the debts provided for in article 68 of the LRF or the transaction provided for in article 10-C of Law No. 10,522/2020; or (ii) when the debtor's assets are identified as being depleted, resulting in substantial liquidation of the company, to the detriment of creditors not subject to the judicial reorganization, as is the case of the Public Treasury. · Depletion will be considered substantial when assets, rights, or future cash flow projections are not reserved sufficient to maintain economic activity for the purpose of fulfilling its obligations. · It will be excepted expressly that, in the event that bankruptcy is decreed by the substantial depletion of the company, the disposals made will be preserved and considered effective, so as not to harm a bona fide third party purchaser. The proceeds of such disposals, on the other hand, should be blocked, with the consequent return to the debtor of the amounts already distributed to any creditors, which will now be available to the court. |

|

Closing of the judicial reorganization · There is two years of judicial supervision. In view of this, it is not possible to close it. When there is a grace period of more than two years, some judges extend the judicial supervision period. An attempt has already been made to close supervision early, but this was not allowed. |

Closing of the judicial reorganization · Supervision will be for a maximum of two years, and judicial reorganization may be terminated prior to that, regardless of the grace period and the closure of the registrations and consolidation of the general list of creditors (article 61). |

|

Fresh start · The LRF does not concern itself with this. Bankruptcy in Brazil is time-consuming and highly contentious. The requirements for closure of the bankruptcy and extinguishment of the bankrupt's obligations are lengthy. |

Fresh start · The changes seek to create a rapid bankruptcy process, with rapid sale of assets (and even the possibility of donating assets without interested parties) and reducing questions on this point, including placing responsibility and a burden on objectors (article 143). · The fresh start will be established in positive law as a principle to be sought in bankruptcy (article 75). · There will also be the possibility of termination of the bankrupt's obligations in shorter periods and under less onerous conditions (article 158), and the rules in force of article 5 of Law No. 14,112/20 must be observed. |

|

Extension of the effects of the bankruptcy · There is no legal provision, but case law admits and confuses extension of the effects of bankruptcy with piercing the corporate veil. |

Extension of the effects of the bankruptcy · Extension of the effects of bankruptcy will be expressly prohibited for limited liability companies. Piercing of the corporate veil must respect the precepts of the Code of Civil Procedure and the Civil Code (article 82-A). Such rules apply only to new bankruptcies. |

|

List of creditors in bankruptcy · The list of creditors is provided for in articles 83 and 84 of the LRF. |

List of creditors in bankruptcy · The order of classification will remain the same, but the table will be simplified, with the elimination of the class with privilege (article 83). · In relation to subordinated creditors, it will be clarified that partners without an employment relationship will hold this classification only in relation to credits taken on without observing strictly fair conditions and market practices (article 83, VIII, “b”). · Such rules apply only to new bankruptcies. |

|

Rapid closure of bankruptcy in the event of absence of assets · There is no express provision in the LRF. |

Rapid closure of bankruptcy in the event of absence of assets · If there are no assets to be collected, or even if they are not sufficient to pay the expenses of the proceeding, the judicial trustee will immediately report this fact to the judge, who, after hearing the representative of the Public Prosecutor's Office, will schedule, via call notice, a ten-day period for interested parties to request what is rightfully due. If the creditors choose to proceed, they will bear the costs of the judicial trustee. Otherwise, the bankruptcy will be terminated after the sale of existing assets within a maximum period of 30 days for personal property and 60 days for real estate. |

|

Sale of assets in bankruptcy · There is no maximum term for the judicial trustee to carry out sale of assets in bankruptcy. · Discussions regarding inadequate price are common. · There is no provision fordonation/return of unsold assets to the debtor. |

Sale of assets in bankruptcy · There will be a maximum period of 180 days for the judicial trustee to proceed with the sale of all the assets of the bankrupt estate. It will be counted from the date of the filing of the notice of collection, under penalty of dismissal, except for reasoned impossibility, recognized by a judicial decision. · The sale will not require consolidation of the general list of creditors. · The sale will not be subject to application of the inadequate and negligent price concept. A third party contesting the sale must make or present a firm offer from a third party and a guarantee 10% of the value of the offer. Raising an undue objection on a point will be an act that undermines the dignity of Justice. · Once the attempt at sale of the assets has been frustrated, and when there is no concrete proposal from the creditors to assume them, the assets may be considered as having no market value and sent for donation or returned to the debtor, if there is no interest in donation. · Pursuant to a resolution passed under article 42, creditors may obtain the assets sold in bankruptcy or acquire them through the formation of a company, fund, or other investment vehicle, with the participation, if necessary, of the debtor's current shareholders or third parties, or through the conversion of debt into capital. |

|

Extinguishment of the obligations of the debtor · Requirements for the extinguishment of the obligations of the debtor laid down in article 158 of the LRF: (i) payment of more than 50% of the unsecured credits; (ii) lapse of the period of five years from the closing of the bankruptcy; or (iii) in the event of conviction for a bankruptcy crime, a period of ten years from the closing of the bankruptcy. |

Extinguishment of the obligations of the debtor · Amendments were inserted to speed up the extinguishment of the debtor's obligations and to allow a fresh start, which will occur in the following events: (i) payment of more than 25% of the unsecured credits; (ii) expiration of three years, as of the decree of bankruptcy, except for the use of assets previously seized, which will be sent for liquidation to satisfy registered creditors or creditors with a request for reserve; (iii) closing of the bankruptcy pursuant to article 114-A (absence of assets of the debtor) or article 156. · The rule in force of article 5 of Law No. 14,112/20 must be observed. |

|

Extrajudicial reorganization · The debtor, provided that 3/5 of the class(es)/subclass(es) of creditors covered by the out-of-court reorganization plan have joined, may request in court approval of the plan, which will be mandatory for all creditors of that (those) class(es)/subclass(es) after approval. · The debtor is free to indicate the class(es)/subclass(es) involved, and may not cover labor creditors, bankruptcy-exempt creditors, and the tax authorities. · The LRF does not provide for a stay period for out-of-court reorganization, but in some cases and in relation to the creditors covered by out-of-court reorganization there are judgements that grant such a suspension pending ratification of the judicial reorganization plan approved by 3/5 of the creditors covered. · There is no protection of absence of succession of the purchaser of the debtor's UPIs in extrajudicial reorganization. |

Extrajudicial reorganization · The quorum for participating will no longer be 3/5 but 50%. The process may begin with the signature of 1/3 of the class(es)/subclass(es) involved, and the reorganization may obtain the 50% needed in the course of the proceeding within 90 days. If such additional adherence is not obtained, the debtor may apply for judicial reorganization. · The labor class may participate in the proceeding, provided that there is collective negotiation with the labor union of the respective professional category. · There will be legal provision for the possibility of a stay period to reach the class(es)/subclass(es) involved as of the request. · There will still be no provision for the absence of succession of the purchaser of a UPI in the obligations and debts of the debtor in possession. |

|

Transnational Bankruptcy · Issue not regulated by the LRF. · In the case of foreign companies that are part of the same economic group as Brazilian companies requesting reorganization in Brazil and whose center of main interest is Brazil, as in the case of offshore vehicles used to raise funds, there is case law allowing such companies to be applicants submitting the request for judicial reorganization. |

Transnational Bankruptcy · Transnational bankruptcy rules will be introduced in Brazil, along the lines of the Uncitral Model Law. · The principles for governing transnational bankruptcy, such as cooperation between judges and maximization of assets, will be established, and institutes (e.g. what is considered foreign proceedings, main proceedings, foreign non-main proceedings and others) will be conceptualized. · The following are the cases in which the provisions relating to transnational bankruptcy may be applied: (i) a foreign authority needing assistance in Brazil for foreign proceedings; (ii) assistance related to proceedings governed by the LRF filed in a foreign country; (iii) foreign proceedings and proceedings governed by the LRF relating to the same debtor underway simultaneously; and (iv) creditors or interested parties with an interest in requesting or participating in proceedings governed by the LRF. · The jurisdiction of the place of the debtor's main establishment in Brazil will be established for recognition of a foreign proceeding and for cooperation with foreign authorities. · There will be express authorization for the debtor and the judicial trustee to act in other countries, regardless of judicial decision, provided that the provision is admitted in the country where the foreign proceeding is being processed. · With respect to access to the Brazilian jurisdiction, the provisions will clarify that (i) the foreign representative will be entitled to submit filings directly with the Brazilian judge; and (ii) foreign creditors will have the same rights as granted to domestic creditors. · The documents to support the application for recognition of foreign proceedings and the effects of such recognition will be indicated. · Rules for the coordination of competing cases will be provided for. |

|

Application of the Code of Civil Procedure · The suppletory application of the Code of Civil Procedure is provided for in the LRF. However, as the new CPC establishes the counting of time limits in business days and restricts when interlocutory appeals may be filed, debates have arisen regarding application of the new rules to bankruptcy proceedings. |

Application of the Code of Civil Procedure · It will be expressly provided that all time limits provided for in the LRF will be counted in calendar days and that the applicable appeal against the decisions rendered in the course of the proceedings will be the interlocutory appeal, unless otherwise provided for in the LRF. · The LRF will also give priority to bankruptcy proceedings, except for habeas corpus and the priorities established in special laws. |

|

Matched transactions and derivatives · Without treatment in the LRF and in practice, early maturity and offsetting have been allowed. |

Matched transactions and derivatives · The possibility of early maturity and offsetting will be provided for by law, and any remaining claim will be subject to judicial reorganization, unless there is a fiduciary guarantee. |

|

Tax issues · When judicial reorganization is granted, the applicant must submit a clearance CND (article 57). However, since the law that provides for tax installments was slow to be enacted and, when it was, it received criticism, the case law has been softening this requirement. · The regulated tax issue is the absence of succession of the purchaser of an IPU in the judicial sale approved in the plan, provided that such purchaser is not (i) a partner of the bankrupt company or a company controlled by the debtor; (ii) a relative, in a straight or collateral line up to the fourth (4th) degree, by blood or by marriage, of the debtor or a partner of the bankrupt company; or (iii) identified as an agent of the debtor with the purpose of defrauding the succession. |

Tax issues · The requirement of article 57 will continue. · Possibility of installment payment of taxes due on capital gains from the judicial sale of a UPI: Corporate Income Tax (IRPJ) and Social Contribution on Net Income (CSLL) due on capital gains may be paid in installments. · Acts of constriction of assets in the scope of tax foreclosures: despite the discretionary power of the tax foreclosure court to order acts of constriction of assets, the reorganization court has the power to order the substitution of such acts that fall on capital assets essential for the maintenance of the business activity, to be exercised through judicial cooperation. · Payment of tax debts: once the judicial reorganization proceeding has been granted, federal tax debts may be settled on a consolidated basis within 120 months. Payments will be calculated in such a way that those due in the first years are lower than those due in subsequent years. As for debts managed by the Brazilian Federal Revenue Service, up to 30% of the consolidated debt may be settled using tax loss credits and the remainder may be paid in 84 installments. The value of the installments will also be lower in the first years of payment. · Other modalities of installment payment are also available, under the terms of Law No. 10,522/2002, as amended. · Settlement: once the processing of the judicial reorganization has been granted, the taxpayer may submit a proposed settlement to the National Treasury Attorney's Office. The conditions of the settlement must include payment within 120 months, reductions of up to 70% in the amount of the debt, among other things. · Ongoing judicial reorganizations may benefit from article 10-C of the Law No. 10,522/02, which deals with the possibility of tax settlements, provided that the requirements of article 5 of Law No. 14.112/20 have been observed. |

- Category: Tax

Leonardo Martins e Matheus Caldas Cruz

With the enactment of Complementary Law No. 189/2020, published on December 29, 2020, the State of Rio de Janeiro internalized ICMS Agreement No. 87/2020, entered into by the National Tax {Revenue} Policy Board (Confaz), to establish the Special Program for Installment Payment of Tax Debts of the State of Rio de Janeiro (PEP-ICMS) related to ICMS, IPVA, and ITD tax debts. The program establishes reduction of legal penalties and late payment chargers resulting from taxable events occurring up to August 31, 2020, whether or not they are registered as outstanding debt.

Complementary Law No. 189/2020 also internalizes ICMS Agreement No. 76/2020, which authorizes the State of Rio de Janeiro to grant amnesty for punitive fines for non-payment of installments of a debt refinancing program authorized by Confaz, which occurred between March 1, 2020, and July 30, 2020, in addition to reestablishing such installment payment programs and installment plans canceled due to default.

The enrollment to the PEP-ICMS will be conditioned on the prior approval of the request by the competent authority and will occur with the payment of the debt in cash or the first installment, depending on the installment option adopted by the taxpayer.

The maximum period for submitting an application for admission to the program will be 60 days, counting from the date of publication of the law. This period may be extended by an act of the Executive Branch only once and for a period not exceeding 60 days.

Among the conditions for enjoyment of the benefit, the law mandates that taxpayers waive any lawsuits and motions to stay tax enforcement, waiving the right on which they are founded, and any objections, defenses, and appeals filed in the administrative sphere involving the debt to be included in the program.

Absence of payment of more than two simultaneous installments (except the first one), existence of an installment or balance of an installment not paid for more than 90 days, default of the tax due for more than 60 days, or lack of proof of the withdrawal of any litigation involving the installment debt will cause cancelation of the program.

The benefits set out in ICMS Convention No. 87/2020 do not apply to taxpayers that have opted for the Special Unified Tax Collection Arrangement for Microenterprises and Small Companies (Simples Nacional), established by Complementary Law No. 123/06, nor to tax debts that have been subject to a judicial deposit in a lawsuit for which there is already a final decision in favor of the State of Rio de Janeiro.

The following table presents in detail the relationship between the number of installments and the proportion of the benefit granted:

Number of Installments* |

Benefit |

|

Single installment |

90% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 6 monthly and successive installments |

80% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 12 monthly and successive installments |

70% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 24 monthly and successive installments |

60% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 36 monthly and successive installments |

50% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 48 monthly and successive installments |

40% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

Up to 60 monthly and successive installments |

30% reduction in legal penalties and late payment surcharges. |

|

* The installments will be adjusted for inflation per the Selic Rate. ** The installments will have the minimum value equivalent to 450 Reference Tax Units of the State of Rio de Janeiro (Ufir RJ) |

|

Machado Meyer is available to advise on the subject.

- Category: Labor and employment

Rodrigo Seizo Takano, Caroline Marchi, Andrea Giamondo Massei, and Daniel Antonio Dias

When the lights went out on 2020, the plenary session of the Federal Supreme Court (STF) completed on the 18th the judgment of the lawsuits that debated the constitutionality of the application of the TR index in the updating of labor debts (ADCs 58 and 59 and ADIns 5,867 and 6,021).

Concurring with the opinion of Justice Gilmar Mendes, the court decided, by a majority, to rule out application of the TR in the updating of labor debts, defining that, as long as there is no specific legislative solution, the updating should be done as follows:

- Pre-judicial phase: IPCA-E

- Judicial phase, as of the service of process on the defendant: Selic

In the same judgment, the plenary session also softened the way in which adjustment for inflation is applied in existing court cases:

- The following shall not undergo any change: judicial payments already made, in due time and manner, and final decisions, which have defined the types of adjustment for inflation;

- A new rule should be applied retroactively: cases under discussion, that have not become final and unappealable, and decisions that have already become final that did not define the form of adjustment for inflation.

The content of the decision has not yet been made public, but there is already a great deal of debate among jurists as to whether the application of Selic will replace not only the TR, but also the application of interest on arrears of 1% per month, or whether it will be cumulated with the interest on arrears cited. However, from an analysis of the proposed opinion of Justice Gilmar Mendes, which will be confirmed when the ruling is published, the reporting judge makes clear in his reasoning that the Selic rate will replace the adjustment for inflation and default interest currently applicable:

"In addition, I believe that we should appeal to the Legislator to correct the issue in the future, equalizing interest and adjustment for inflation to market standards and, as for past effects, order application of the Selic rate, in substitution for the TR and legal interest, to calibrate, in an appropriate, reasonable, and proportionate manner, the consequence of this judgement.

(...)

On the other hand, ongoing cases that are stayed in the cognizance phase (regardless of whether they have been decided, including in the appeal phase) must be subject to retroactive application of the Selic rate (interest and adjustment for inflation), at risk of a future claim of unenforceability of judicial instrument based on an interpretation contrary to the STF's position (article 525, paragraphs 12 and 14, or article 535, paragraphs 5 and 7, of the Code of Civil Procedure).”

Once the understanding is confirmed, the new rule for adjustment for inflation will have positive implications for companies, since the annual interest rate on labor debts is 12% per year, while the Selic rate is currently below 4% per year. There will also be benefits for workers with the application of the IPCA-E in the pre-judicial phase, as the TR has been at 0% since 2018.

The decision stabilizes the numerous judicial debates on the issues in question, but will also have great impact on companies, which, after publication of the STF’s decision, will have to adapt their contingencies to the new rules.

- Category: Infrastructure and energy

Issuances of debentures had been showing strong growth since 2018, a process that was interrupted, albeit briefly, by the covid-19 pandemic. Just as an example, in 2019, as per a report byValor Econômico, the volume of issuances reached a record level of R$ 33.7 billion, totaling almost 100 issuances, with an average value of R$ 300 million per paper.

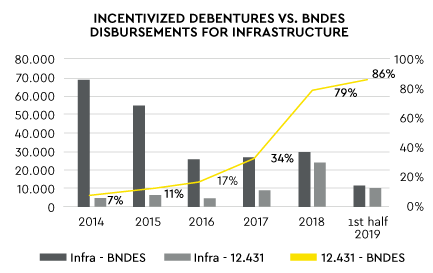

Incentivized debentures, used to finance infrastructure projects, with a focus on the energy and transportation sectors in particular, have shown historic growth. Since its creation in 2012, the total volume of issuances in 2019 exceeded BNDES' disbursements, totaling R$ 24.4 billion and taking the lead as the main instrument for financing infrastructure, according to data from Anbima and BNDES, highlighted in the figure below:

Source: Capital Markets Bulletin, Anbima, June 2019; BNDES, June 2019.

In 2020, the pandemic led to a reduction in the numbers to levels below those of 2018, but still much higher than in 2017. If, on the one hand, the total number exceeds that recorded in 2017, the number of issuances was lower, 35 this year against 49 papers issued in 2017, according to Anbima data.

The positive news is that the average value of 2020 issuances exceeds even the 2019 average, R$ 480 million, and the terms continue to extend, which means that the market believes in the security and liquidity of these papers.

Two factors indicate a considerable high expectation for 2021. First, a series of auctions has been postponed to next year and, as these projects are resumed, they should increase demand for infrastructure debentures. Then, a series of regulatory innovations took place in the telecommunications and sanitation sectors, which today account for less than 5% of the total volume of issuances, if added together.

The telecommunications sector recently saw the publication of Ordinance No. 502/2020, which modernized the regulation of processes for classifying incentivized debenture issuances by companies in the sector. The main innovations were expansion of eligible projects, issues related to project expenses, such as the possibility of reimbursement of expenses, future investments and reimbursement for grant expenses, and, especially, the possibility of financing imported goods. There are also high expectations with the arrival of 5G technology, which will require large investments. This new legal framework and the news in the sector should make incentivized debentures more attractive to finance projects in the sector.

The sanitation sector, in turn, has just received the new Regulatory Framework, which facilitates the concession of services to the private initiative. Dozens of bids are already planned for 2021. By 2030, the Ministry of Regional Development expects that between R$500 billion and R$700 billion will be invested in the sector, which today has the highest demand and expectation for investment in the infrastructure segment. At the same time, private companies account for about 3% of water and sewage service providers. As private players become more involved in the sector, demand for financing will automatically grow. Naturally, the incentivized debentures will now play an important role in financing sanitation projects.

Despite the pandemic, 2020 was a year of important legal milestones for the infrastructure sector. In May, the Chamber of Deputies proposed PL 2646, authored by Deputy Arnaldo Jardim, which, among other innovations, proposes the creation of a new class of infrastructure debentures, papers whose tax benefits would apply directly to the legal entity sponsoring the project. This would create higher yielding papers, more attractive to the market, especially for institutional investors such as large funds. In addition, the possibility of foreign exchange variation in the new infrastructure debentures could attract foreign investors.

The bill also creates greater incentives (50%) for sustainable projects, the so-called green bonds, in the sectors of renewable energy, energy efficiency, pollution prevention, and control, clean transport, sustainable water, and wastewater management, solid waste, climate change adaptation, and sustainable buildings.

Currently, bill 2646 has been sent to the Labor, Administration and Public Service; Finance and Taxation; and Constitution and Justice and Citizenship committees, and is subject to conclusive consideration, that is, it does not need to go to the floor of the Chamber of Deputies, and must only be approved in the committees.

The year 2020 was especially important for sustainable projects and green bonds

The federal government has updated Decree No. 8,874/16, which regulates Law No. 12,431/11, through the promulgation of Decree No. 10,378/20. Thus, the scope of the law was extended to the financing of infrastructure projects that present environmental and social benefits, through the possibility of classifying the issuance of incentivized debentures. The sectors of urban mobility, clean energy, and basic sanitation are covered. Apart from the issue of the nature of the projects, Decree No. 10,378/20 also allows the inclusion of smaller projects or projects that are not necessarily developed by concessionaires, permissionaires, or holders of public service authorization.

We see a significant increase in funding for sustainable projects through green bonds. Since January of 2020, according to data from the database of Sitawi, R$ 3.96 billion in green, transitional, or sustainable debentures were issued. All these papers were given a second opinion by specialized consultants.